The last hand-painted archways in Singapore: A family legacy

Painter Leong Fong Wah, 70, is holding on to a dying craftsmanship, continuing his father’s legacy of painting and building decorative archways. Lianhe Zaobao lifestyle correspondent Tang Ai Wei finds out how his traditional craft is surviving in an increasingly computerised and outsourced industry.

When the media interviewed Leong Fong Wah in 2008, he was one of two — or even the only — remaining craftsmen still hand-painting decorative archways and stage backdrops. Seventeen years later, this profession has yet to see any new blood.

In the dim art studio, cluttered with decorative archways old and new, and strewn with scattered tools, the solitary silhouette of a 70-year-old man lingers, speaking softly to a past only he remembers. His hands have known the weight of a paint brush for more than five decades. Leong recalled that the old days were more “fun” — a time when creative freedom felt expansive and unrestrained.

Decorative archway that welcomed Singapore’s founding father

Leong Shin Wah Art Studio was named after Leong Fong Wah’s father. It was the first time I came across a father and son whose names differed by just one character — a naming pattern shared by Leong’s two younger brothers, both of whom also carry ‘Wah’ in their names. According to Leong, their father chose the names in hopes that his sons would one day take over the family business.

Leong Shin Wah, who hailed from Fuzhou, was a painter who began practising this craft in Singapore in the 1950s. Starting out near the Great World Amusement Park area in River Valley, he later relocated to Joo Chiat. Leong Fong Wah joined his father in the studio after finishing sixth grade.

Advertisements for goldsmiths, car dealerships, bak kwa (肉干, a salty-sweet dried meat product similar to jerky) sellers, pharmacies and so on were all hand-painted onto backdrops and archways, providing an important source of income for art studios.

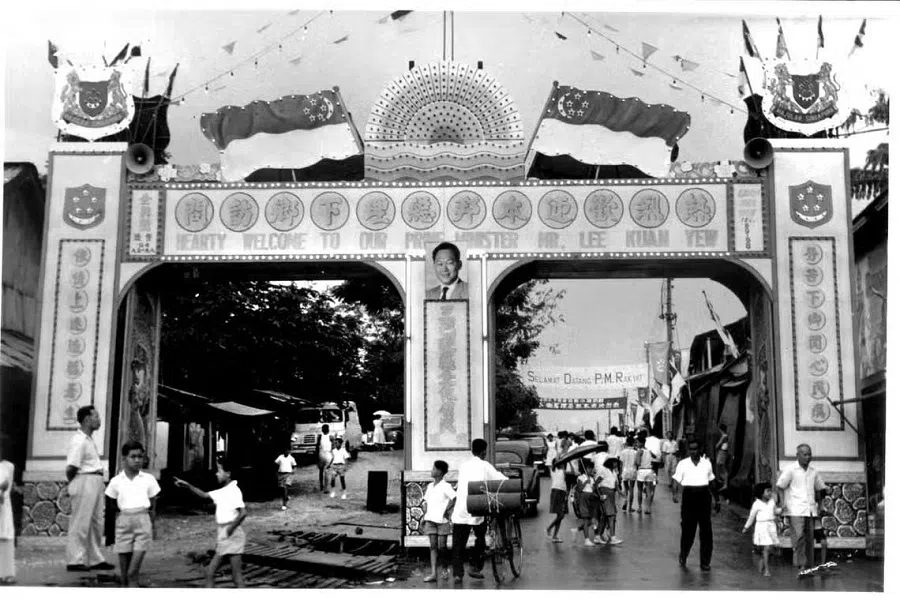

Turning the pages of the albums, the yellowed photographs whisper the tales of the studio’s vibrant past. Singapore’s late founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew often visited rural areas in the 1950s and 1960s, and the many archways and canopies that welcomed him were designed, produced and erected by Leong Shin Wah.

Theatrical stages of a bygone era were not only performance spaces for opera troupes but also advertising spaces for businesses. Advertisements for goldsmiths, car dealerships, bak kwa (肉干, a salty-sweet dried meat product similar to jerky) sellers, pharmacies and so on were all hand-painted onto backdrops and archways, providing an important source of income for art studios.

Leong Fong Wah recounted, “Business was booming back then. Many events and occasions required decorative archways, such as theatrical stages, temple fairs and celebrations. We also created props and backdrops for major events, and my father even went to Thailand to build archways for an international trade fair. He was also a master dragon dance prop maker, and created Singapore’s first luminous dragon in 1966.”

Keeping the craft alive

After his father passed away, Leong, then still shy of 30, formally took over the business. He relocated the art studio to a two-storey building in Ubi Industrial Estate, handling everything from fabrication to painting.

“Back then, there were five or six other studios like ours, each operating independently,” Leong said. “We even made the very first Chinese New Year light displays in Chinatown in the 1980s. But with technological advancements, design work became increasingly computerised. Coupled with import competition from China and neighbouring countries, our orders dwindled.”

... the craft of dragon-making has already been forced into “early retirement” due to foreign competition. While it costs about S$4,000 (US$3,081) to make a dragon in Singapore, importing one from Indonesia or China only costs S$1,000.

Adapting to the times, Leong now outsources the designing and printing of the images, handling only the post-processing. A decorative archway, which would take about three days to hand-paint, can now be designed and printed in a single day with a computer, at half the cost. Today, only a portion of long-time clients still insist on hand-painted works. But since decorative archways can be used for many years, returning clients are far and few between.

Similarly, the craft of dragon-making has already been forced into “early retirement” due to foreign competition. While it costs about S$4,000 (US$3,081) to make a dragon in Singapore, importing one from Indonesia or China only costs S$1,000.

As traditional sources of income dwindled, Leong diversified his services to keep the business afloat, expanding into signage production and installation, and the restoration of faded temple murals. He later added the word “advertising” (广告) to the name of the studio to reflect this shift.

Holding on to this legacy as long as possible

Chinese New Year is his peak season, when he installs God of Wealth and zodiac forecast displays in the heartlands. This income would sustain him for several months, with temple celebrations and Hungry Ghost Festival orders helping him get by the rest of the year.

“I’m the only one left. There are also fewer ritualistic events these days. Our era is over.” — Leong Fong Wah, Painter

“Business is tough,” Leong said wryly. “I can’t afford to charge too much. Thankfully the factory rent is reasonable and I work alone, hiring help only when needed. It’s enough to get by. This profession is demanding. Others have either retired or closed shop. I’m the only one left. There are also fewer ritualistic events these days. Our era is over.”

The writing seems to be on the wall even during his father’s time. The constant moving of the studio, along with soaring rents, had worn the elder Leong down. He even contemplated giving up at one point, going so far as to discard precious hand-drawn drafts.

Though deeply saddened by the loss, the younger Leong persevered, determined to keep the business going. Now, despite the changing times and his children’s disinterest in taking over, he has never thought of retiring. He only wishes to hold on to this legacy for as long as he can.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “昔日牌楼成追忆 七旬手艺人画师成守艺人”.