Hard work, little reward: What’s driving China’s ‘lying flat’ generation

Despite growing scepticism toward the system and traditional paths to success, many young Chinese still value personal effort and believe in their ability to shape their own future. EAI researchers Shan Wei and Chua Jing Yee explain.

In recent years, the concept of “lying flat” (躺平) has become popular among young people in China. It refers to choosing a simple, low-pressure life over the pursuit of career success and material wealth. Instead of overworking, many young people prefer minimalism, rest and a better work-life balance.

This trend has important policy implications. It reflects changing values among younger generations, which may affect labour productivity, economic growth and even fertility rates. The Chinese government quickly recognised the “lying flat” mindset as a challenge to its ambitious vision of the Chinese dream.

However, these efforts have not fully addressed the underlying issues. To craft effective responses, it remains essential to understand the deeper structural and socioeconomic causes behind the rise of “lying flat”.

... younger people are rethinking the role of hard work and success, which suggests that “lying flat” may reflect a long-term shift in values — not just a short-term reaction.

Some link the rise of “lying flat” to recent issues like the Covid-19 pandemic, economic slowdown and high youth unemployment. But deeper, long-term factors may also be shaping this mindset — such as intensified competition, overwork culture and a growing desire for personal fulfilment over traditional success.

By comparing different age groups, we can see that younger people are rethinking the role of hard work and success, which suggests that “lying flat” may reflect a long-term shift in values — not just a short-term reaction.

Broader move away from traditional work-centred norms

Understanding generational shifts in attitudes toward work expectations and life priorities is crucial to uncovering the rise of the “lying flat” phenomenon. Survey data provides insight into these changes by asking about the perceived role of work in society, the value placed on hard work, and the importance of leisure time.

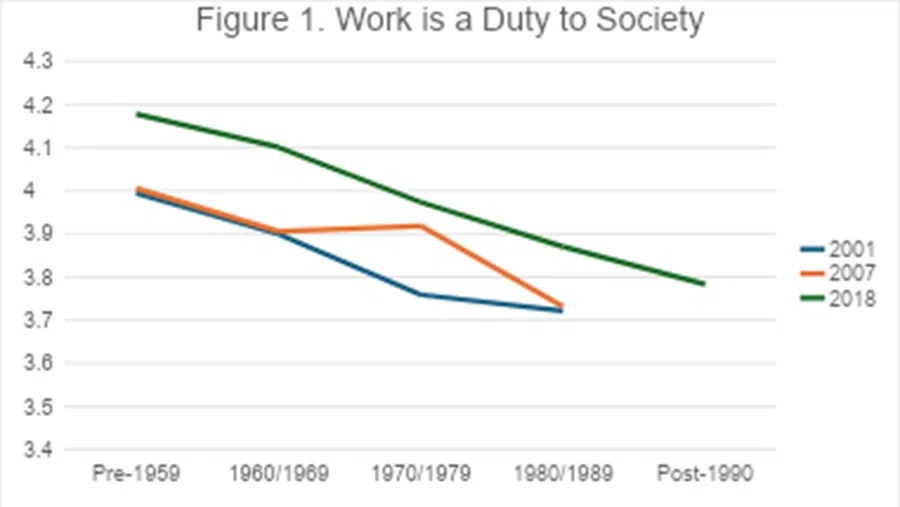

As shown in Figure 1, the responses to the question “Is work a duty to society?” in the World Values Survey on a scale of 1-5 reveal a generational divide. Older cohorts show the highest agreement, averaging above 4.1 in 2018, whereas the average for those born after 1990 drops to below 3.8. This reflects not only the differences in perception of work between generations but across time, where earlier generations viewed work as a social duty while younger Chinese increasingly see it as a personal choice.

In addition to the findings above, two other survey items point to similar generational shifts in values. Younger respondents are less likely to see hard work as a desirable trait for their children and are more likely to emphasise the importance of leisure time. These patterns, though less extensively analysed here, further underscore a broader move away from traditional work-centred norms.

The lowest confidence is found among those born in the 1980s and 1990s, who are the most active in the labour market and often find themselves trapped in high-pressure work environments with fewer career advancements.

Disillusionment with meritocratic promises of the system

Changes in attitudes towards work in China may be closely linked to generational perceptions of societal opportunities. Over the past 20 years, as competition and workload have intensified, people’s views on hard work and competition may have shifted, leading to growing scepticism about their rewards and the feasibility of upward mobility.

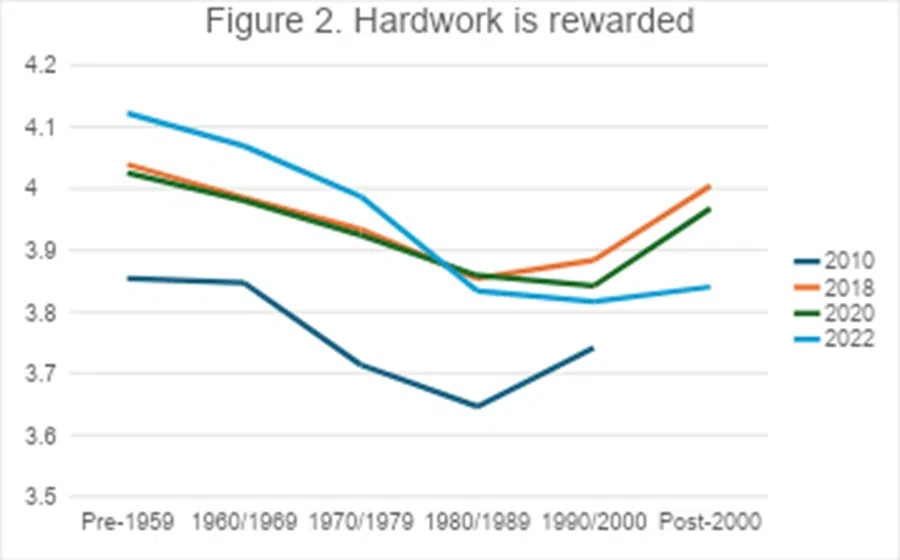

Figure 2 examines the responses from the CFPS survey to “Hard work is rewarded” on a 1-5 scale. While overall averages remain high between 3.5 and 4.2, the figure exhibits a U-shaped pattern.

The lowest confidence is found among those born in the 1980s and 1990s, who are the most active in the labour market and often find themselves trapped in high-pressure work environments with fewer career advancements. This suggests that this generation is sceptical about the rewards of hard work within the current economic realities, in contrast to the youngest cohort, who may still hold idealistic views.

Other survey items also reflect generational scepticism toward the fairness of the opportunity structure. Younger respondents are less likely than older generations to believe that intelligence is rewarded in today’s society, and they also express less support for the idea that competition is inherently good. Together, these views suggest a growing disillusionment among the youth with the meritocratic promises of the system.

Wanting to believe in individual effort

Over 40 years of market reform, privatisation and opening up in China have woven individualism and the pursuit of self-fulfilment into the country’s social fabric. These transformative shifts in values have likely influenced societal attitudes toward work and diligence. It is crucial to examine how different generations in China perceive self-reliance, personal effort and confidence in the future.

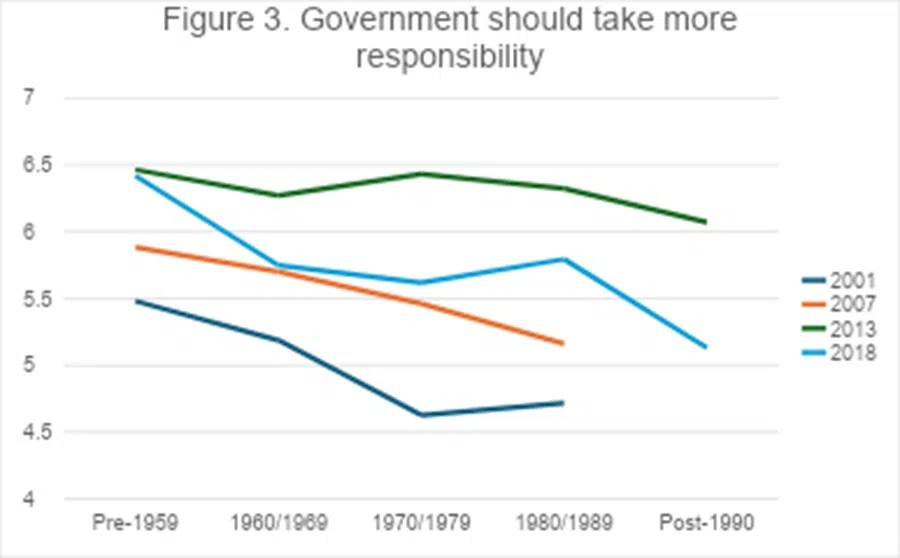

This divide is illustrated through Figure 3, where attitudes for government responsibility and individual self-sufficiency are measured on a 1-to-10 scale, where higher scores indicate a stronger preference for government support.

Overall results range from 4.5 to 7, signalling a slight tilt toward collective support, though differences between age groups exist. Older cohorts, especially those born before 1960, consistently express greater support for state-led welfare, averaging around 6.5 in 2018. This divergence is largest in the 2018 survey, where younger respondents, particularly those born after 1990, lean more heavily toward individual responsibility, with scores closer to 5.

... younger Chinese tend to embrace the idea that personal effort and agency, rather than state support or social networks, are key to achieving a better life.

Several other survey items confirm a broader pro-market and individualistic orientation among younger respondents. They are significantly less likely than older generations to believe that personal connections matter more than individual ability, suggesting a stronger commitment to the idea of meritocracy — even as they grow sceptical about how it works in practice. They are also more optimistic about their capacity to improve their living conditions and express greater confidence in the future.

Taken together, these patterns indicate that younger Chinese tend to embrace the idea that personal effort and agency, rather than state support or social networks, are key to achieving a better life.

China’s youth seek control and their own path

The findings from above reflect growing disillusionment with meritocracy and hard work among Chinese youth. While many no longer see work as a reliable path to success, their continued belief in personal responsibility suggests that policies promoting fairer opportunities and social mobility could help rebuild confidence.

Supporting innovation, alternative careers and better childcare services would help re-engage youth in the workforce and promote long-term stability.

In recent years, the Chinese government has taken steps to address such concerns. It has repeatedly criticised the “996” schedule — 9am to 9pm, six days a week — declaring it a violation of labour laws that should be curbed. In the 2025 NPC work report, Premier Li Qiang denounced the excessive competition. Companies like JD.com and Midea have also introduced mandatory leave-on-time policies to reduce burnout and improve work-life balance. However, these efforts remain selectively enforced and mostly limited to high-profile firms in major cities, with little impact on broader norms.

To build on these measures, more comprehensive reforms are needed. Improving job security, addressing wage stagnation and promoting fair hiring are critical. Equally important is expanding access to affordable housing and financial tools to ease long-term burdens. Supporting innovation, alternative careers and better childcare services would help re-engage youth in the workforce and promote long-term stability.

An initial version of this article was first published as an EAI Background Brief.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)