How a 140-year flood caught Beijing and nearby cities off guard

After experiencing the hottest June on record for the city, Beijing is now witnessing the most rainfall in the 140 years since records began. How did Typhoon Doksuri bring the prolonged heavy rainfall to northern China thousands of kilometres away from its landing point?

(By Caixin journalists Wang Kerou, Wang Shuo, Kang Jia, Zhao Dan, Zhou Qianqian, Wang Xiaolu, Zhang Fangzhou, Lv Siyu, Zhang Shuning, Lu Yicai, Yang Yuqi, Huang Yanhao and Denise Jia)

(Photos: Ding Gang and Zhang Ruixue/Caixin)

Wang Jianyong, a resident of Xiehejian village in the mountainous suburban region west of Beijing, walked to attend a fellow villager's funeral on the morning of 31 July. There was moderate rain.

The Yongding River, which runs through the community, was rising quickly. By 10am, mud and rocks were pouring down on the road from the hills above. Wang and several fellow villagers took refuge in a nearby tunnel.

When he returned home at 11:30am, Wang found that a ten-metre-wide spillway had overflowed with muddy, black water and washed away half of the neighbouring house belonging to his brother. He went to investigate and - over the din of rushing floodwaters - heard weak cries from inside. With the help of some friends, Wang broke a window to enter the home and found his sister-in-law struggling in floodwaters that were up to her neck. She said her husband and daughter were both washed away.

Over the next few days, Wang searched behind every rock along the spillway but couldn't find his niece or brother. He was told his niece, a 21-year-old junior at Beijing Sport University, may have been rescued but she wasn't in any of Beijing's hospitals. "She has always been one of the top two students in our whole town," he told Caixin, trying to hold back tears.

Xiehejian, on the right bank of Yongding River and surrounded by mountains, was among the hardest hit villages by flooding in the Mentougou district of Beijing. Typhoon Doksuri dumped 452.6 millimetres of precipitation over three days through 1 August, the most rainfall for the capital city in the 140 years since records began.

... the latest breaching of riverbanks killed at least 22 people and forced the relocation of 1.5 million across the capital and neighbouring Tianjin and Hebei provinces as of 4 August.

The 72-hour deluge exceeded downpours lasting 20 hours in 2012 and 55 hours in 2016. Those storms also brought flooding to Beijing and set daily rainfall records at ten meteorological stations in neighbouring Hebei province as of 31 July. Overall, the latest breaching of riverbanks killed at least 22 people and forced the relocation of 1.5 million across the capital and neighbouring Tianjin and Hebei provinces as of 4 August.

Scientists suspect climate is behind the latest disaster. Global warming is speeding up the water cycle and increasing rainfall around the world, Wei Ke, deputy director of the Monsoon System Research Center at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, told Caixin. Research shows that for every 1 degree Celsius rise in global temperature, worldwide precipitation will increase by 2% to 3%, he said. "So I believe that later analysis of the cause of this heavy rain may also reveal that climate change played a role," Wei said.

In the main part of Beijing city, located on a plain, flood damage was less severe than in the mountainous suburbs. Still, several trains were stranded before arrival to the capital as the tracks were buried under mud and rocks. Thousands of passengers had to trudge for miles to nearby villages. Videos posted on social media show aircraft grounded at a water-logged Beijing Daxing International Airport. Nearly 400 flights were cancelled there on 31 July.

The airfield, which lies in low land between the Yongding River to the south and the Yongxing River to the north, becomes a natural flood plain.

Flood-sieged Zhuozhou

Downstream and 62.5 kilometres southwest of Beijing's Mentougou district, Zhuozhou was the worst-hit urban centre in Hebei. Local authorities activated red alerts for all six rivers that cross the city, which lies in a flat plain. More than one-sixth of the municipality's roughly 660,000 residents were evacuated while six metres of water submerged parts of the town.

In Xiliuzhuang village, about 23 kilometres northwest of Zhuozhou, Li Yuzhen (pseudonym) heard a broadcast from the village loudspeaker at 5:44am on 31 July but couldn't make out what it was saying. She then opened up a village group chat on WeChat and heard an audio message: "The river is overflooding. You should go to the second floor, or go to someone's home with a second floor. Quick!"

When Li opened her door, the water had spread to her front yard. She awoke her family and some of her neighbours to move to the second floor of their house. The water quickly rose to two metres high.

Twelve people stayed there for almost 48 hours while a power outage blacked out the entire village. With on and off mobile phone service, she sent out numerous help messages through the village group chat. She was told that the flooding was so deep that rescuers would have difficulty reaching her.

Eventually, the group was rescued and transported to a middle school in Zhuozhou that was housing thousands of other residents. Many villagers told Caixin that they received evacuation notices hours before the floodwaters rose, instructing them to stay on the second floor or go to the middle school.

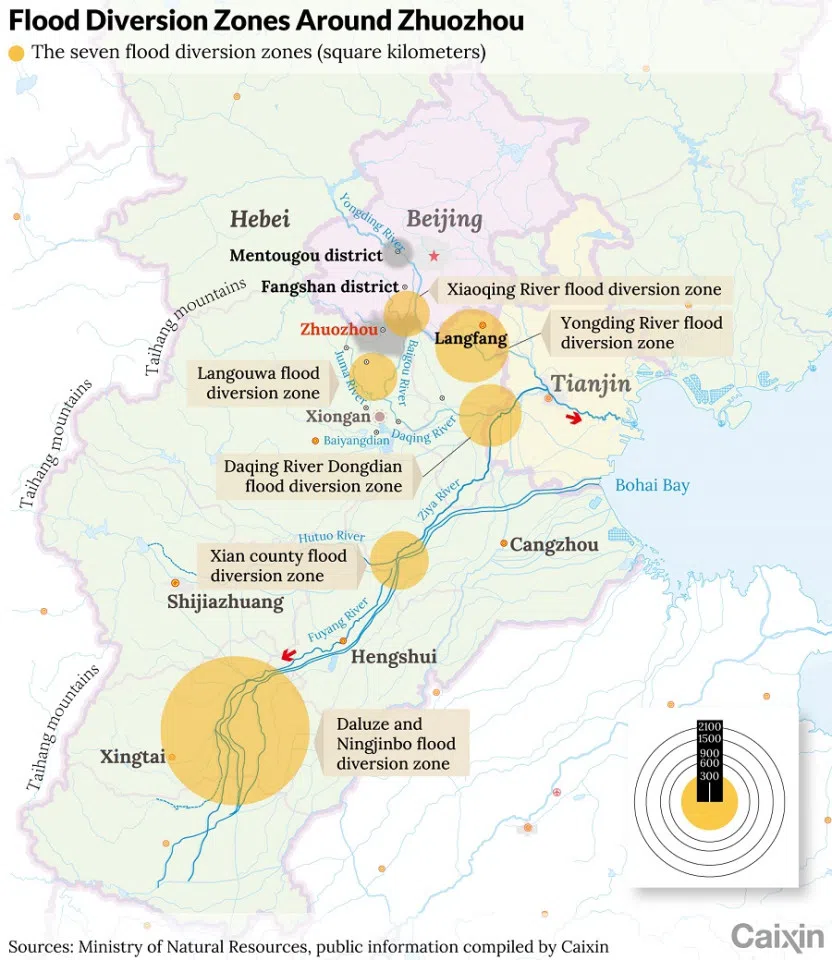

Flood diversion areas

The rivers that flow through Zhuozhou originate from Taihang Mountain where the rain hit the hardest. When upstream tributaries are expected to receive more precipitation than they can handle, reservoirs will usually release some water in advance so they have the capacity to relieve pressure during a storm's peak.

Zhaitang Reservoir located in Mentougou did so on 30 July, followed by Guanting Reservoir the next day. All the water flowed to Zhuozhou through the Yongding and Xiaoqing rivers.

As the upstream flood continued to pour down, local water resources authorities decided to use the flood diversion areas, which use lakes or rivers to hold water from upstream to alleviate the flood pressure downstream. As of 2 August, Hebei province had used seven flood diversion areas, "playing a significant role in flood diversion and greatly reducing the flood control pressure in Beijing and Tianjin," according to Hebei Daily, the official newspaper.

Three of the seven flood diversion areas can reduce flood control pressure on Xiongan New Area, a new economic zone some 100 kilometres southwest of Beijing built in 2017, to ease some of the capital's metropolitan burdens; and one is designed to safeguard Tianjin and some major infrastructures such as the Tianjin-Shanghai railway and North China Oilfield, according to an article by a research team at China Agricultural University.

But the use of these flood diversion areas can cause flooding in Zhuozhou city, said Li Juntong, an engineer at Zhuozhou Water Resources Bureau, in a research paper published in 2010.

[the rescuers] are not familiar with the geographical location and road conditions, and the muddy water made it difficult to judge direction, greatly affecting the speed they can approach the stranded people.

As of 1 August, 225 square kilometres of Zhuozhou region were under water, affecting nearly 134,000 residents, leaving the local government pleading for emergency assistance, local officials said.

The rain stopped by afternoon of 1 August, but many residents were still trapped in high-rise residential buildings in the city. The rising water was covered with white fog, making visibility less than 100 metres. Rescuers said poor visibility complicated rescue efforts.

"We can't see the road," said a rescue commander at Hebei Provincial Firefight Brigade. "Many trees and fences are submerged in the water, which can pop out inflatable boats."

Power outages and shortages of rescue equipment and gasoline also made the rescue difficult. Several rescuers told Caixin that they are not familiar with the geographical location and road conditions, and the muddy water made it difficult to judge direction, greatly affecting the speed they can approach the stranded people.

Why not evacuated

Many residents question why Zhuozhou residents were not evacuated before the use of flood diversion areas. A person from the Beijing water resources system said that all the downstream water resources authorities were notified of the water release by upstream reservoirs as of the night of 30 July. "They should estimate the water flow and arrange evacuation ahead of time," the person said, "The problem was that the relocation plan and emergency measures were not in place in time."

Wang Duan (pseudonym), who lives in Mengjiajie village downstream of Juma river, said that villagers saw the river rising on 30 July. By noon, the head of the village notified residents that they were told to evacuate to another town. But the head said he considered the evacuation plan was "unrealistic" as the other community's elevation is about the same as his village, and is 17 kilometres away. He told residents to move to higher places in the village. Later more evacuation notices were issued, but providing no information about how much water and when it will be released from upstream. Most villagers still chose to ignore the notices, Wang said.

By the morning of 1 August, cell phone coverage went out and residents couldn't call for help.

By 3pm that day, water submerged village roads. The evacuation bus was nowhere to be seen. The village head told residents to leave on their own. But vehicles could no longer move amid the rapidly rising waters.

At 7:20pm, the village head told people floodwaters would crest within two hours. Villagers started to panic. By the morning of 1 August, cell phone coverage went out and residents couldn't call for help.

Mengjiajie village was not the only village that failed to evacuate. When a region hasn't seen a major flood for a long time, people become less alert, said Cheng Xiaotao, deputy chief engineer at the China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research. People usually become more vigilant after a major flood. The last time a comparable flood hit the region was in August 1963, which killed thousands in northern China.

Before the flooding season this year, Beijing flood control authorities conducted a drill, assuming how Beijing should respond if the Yongding and Chaobai rivers flooded, Cheng said. But the drill mainly targeted Beijing's inner city. A lesson from this disaster is that flood control in mountainous areas should also be paid more attention, said Jia Shaofeng, a researcher at the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

... water resource authorities have turned natural riverbanks in the mountains into hard-surfaced channels. Natural riverbanks have obstacles such as rocks, which can slow down torrents; after smoothing the riverbanks, floodwaters can flow faster downstream.

As many mountainous areas near Beijing have developed tourism in recent years, water resource authorities have turned natural riverbanks in the mountains into hard-surfaced channels. Natural riverbanks have obstacles such as rocks, which can slow down torrents; after smoothing the riverbanks, floodwaters can flow faster downstream. "It's like a car driving down a steep slope," Cheng said. "Without breaking, it can run faster and faster."

Downstream cities such as Zhuozhou and smaller rivers have a relatively lower standard for flood control. For example, a dam on a large river is usually built to guard against a 50- or 100-year flood, one that only occurs once or twice per century. But dams on small- and medium-sized rivers are designed for smaller floods that may occur once every five or ten years, said Jia from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Zhuozhou's flood control standard was designed for floods that occur once every seven years, according to the research by Li at Zhuozhou Water Resources Bureau.

Global warming

How did Typhoon Doksuri, which landed in southern China's Fujian province on 28 July, bring prolonged heavy rainfall to northern China thousands of kilometres away from its landing point?

Although the rainfall in northern China was related to the typhoon, it was not caused by the typhoon itself. As Doksuri's rain clouds headed north, a subtropical and continental high pressure system in the atmosphere and a warm and dry weather impacting most of China in the summer, blocked their passage.

When large amounts of vapour in Doksuri's rain clouds met the subtropical and continental high pressure system, the pressure difference strengthened the southeast wind, pushing the vapour further north, Wei, at the Monsoon System Research Center, said. When the vapour was blocked by Taihang Mountain southwest of Beijing, it formed clouds of extreme rainfall, he said.

In the future, more extreme weather events, such as heat waves, heavy rainfall and cold waves, may become the new normal. - Hu Xiao, chief meteorological analyst of China Weather Network

Mentougou and Fangshan districts of Beijing and Lincheng in Hebei, all located at the east slope of the mountain, where the rain clouds and southeast wind were blocked by the mountain, suffered the heaviest rainfall.

Even though the heavy rains were affected by common weather systems and the particular terrain, rain with such intensity and duration is unusual in northern China, Wei said.

Since mid-June, a heat wave has swept across large swathes of China, hitting northern regions particularly hard. Beijing reported 15 days in June when the average temperature exceeded 35 degrees Celsius, making the month the hottest June on record for the city.

The heavy rains following the heat wave would make the public aware of the increasing incidence of extreme weather and climate event after global warming, said Hu Xiao, chief meteorological analyst of China Weather Network. In the future, more extreme weather events, such as heat waves, heavy rainfall and cold waves, may become the new normal, Hu said.

Zhang Meiting and Yang Han contributed to this report.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as "Cover Story: How a 140-Year Flood Caught Beijing and Nearby Cities Off Guard". Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

Related: Floods in China: Can the Three Gorges Dam weather 'once-in-a-century massive floods in the Yangtze River'? | Chongqing residents on worst floods in 40 years: This has not been a good year | Zhengzhou floods: Netizens berate local government and media for inadequate response | Giant Buddha and sponge cities: Combating floods where three rivers meet

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)