Not all heroes shout: How The Legend of Hei 2 reimagines Chinese animation

While Ne Zha signals industrial ambition and cultural export, The Legend of Hei reveals a gentler path — hand-drawn, community-made and emotionally grounded in coexistence rather than spectacle. Lianhe Zaobao visual journalist Fio Zhang explains its appeal and understated value.

In recent discussions of the rise of Chinese animation, Ne Zha is often positioned as a representative milestone: a highly industrialised 3D animation production pipeline, a modern reconfiguration of Eastern mythology and a clearly articulated ambition for cultural export. The film resonates strongly with popular narratives of self-empowerment while simultaneously functioning as a form of national-level storytelling. This trajectory is neither accidental nor avoidable; rather, it reflects a necessary path in the industrial development of Chinese animation.

Making animation out of love

Yet beyond this dominant narrative, another softer but equally significant trajectory has taken shape over the past decade. As the post-90s and post-00s generations came of age, a wave of Chinese 2D animation emerged on online platforms, driven largely by small teams of young people. Many of these creators were recent graduates who had a niche subculture passion with limited access to funding and industry resources. They operated with minimal budgets, and often relied on unpaid or underpaid labour sustained primarily by passion rather than profit. In this sense, these works were quite literally done out of love.

... the project began with an initial budget of just 3,000 RMB (US$430), being almost entirely a personal experiment.

The 2D animated series The Legend of Hei (罗小黑战记) tells of a small cat-like spirit displaced by urban expansion and forced to navigate a world shared by humans and other supernatural beings. It raises questions of belonging, identity, and coexistence.

Works such as Mojospy (2009), Fei Ren Zai (2018) and Yao: Chinese Folktales (2023) did not rush to construct grand historical metaphors or national allegories. Their concern lies not with monumental narratives, but with the position of the self within the country and the world.

The Legend of Hei occupies a crucial position within this trajectory, and the recent release of The Legend of Hei 2 renders its contemporary orientation even more explicit. First released online in 2011 as a series of Flash-animated shorts by director MTJJ, the project began with an initial budget of just 3,000 RMB (US$430), being almost entirely a personal experiment.

Such extreme material constraints meant that it could not go by the production process of the mainstream animation industry. Instead, it adopted a low-cost, long-term and high-quality creative method. It was within this context that the series gradually gained its audience, relying on its light narrative rhythm and its focus on intimate, everyday character interactions rather than spectacular visual display.

Over the following decade, the project transitioned from web-based animation to theatrical production while consistently retaining its 2D hand-drawn visual language and its deliberately understated narrative approach.

Around the mid-2010s, following the commercial success of animation film Big Fish & Begonia (大鱼海棠), the Chinese animation industry experienced a brief but intense wave of speculative investment. In a field long sustained by only a small number of persistent practitioners, MTJJ and his project inevitably became one of the objects of attention. Yet, unlike many contemporaneous works that either dissolved, were absorbed into standardised production pipelines, or underwent stylistic transformation in response to platform demands, The Legend of Hei maintained a remarkable continuity in both form and narrative ethos.

Over the following decade, the project transitioned from web-based animation to theatrical production while consistently retaining its 2D hand-drawn visual language and its deliberately understated narrative approach. Rather than a break, this shift exemplified a continuity of creative ethics. This slow and cautious evolution allowed it to carve out a path unlike the dominant industrial model, by resisting urgency, spectacle and grand declaration in favour of continuity, intimacy and reflection.

Visual restraint as a contemporary strategy

In 2D animation, the human touch remains the most effective way to express the authenticity of human experience. Today’s 2D animations do not simply revive “Eastern aesthetics” as a stable heritage. Rather, they selectively reinterpret and reassemble elements associated with East Asian visual traditions, such as restraint, negative space, everydayness, or moral ambivalence within new production structures and affective regimes.

When discussing Eastern aesthetics in Chinese animation, the legacy of the Shanghai Animation Film Studio remains indispensable. Classic works such as Havoc in Heaven (1961), The Nine-Colored Deer (1981) and Lotus Lantern (1999) represent not merely a historical style, but an aesthetic system rooted in traditional painting practices: soft yet resilient linework, restrained motion design, the interplay between void and substance, and a muted, carefully balanced use of colour. Rather than pursuing sensory impact, this tradition foregrounds rhythm, pause, and emotional openness.

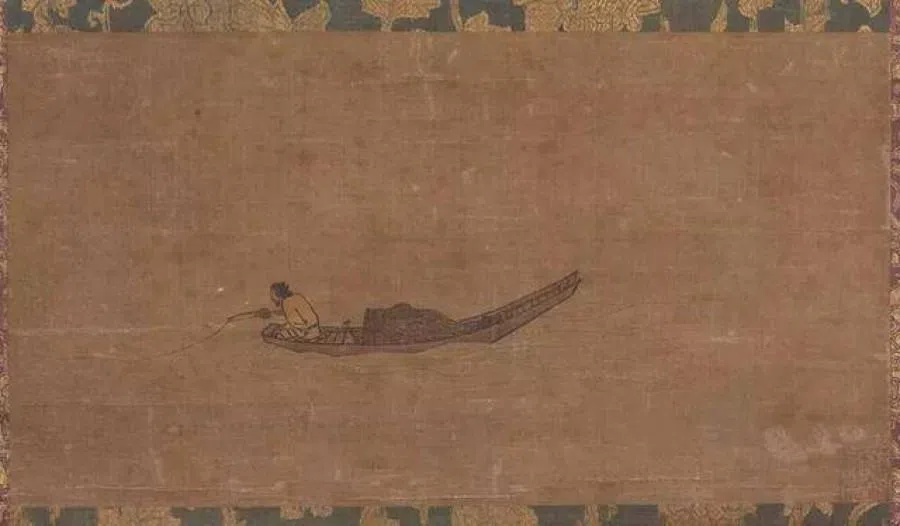

This visual logic can even be traced further back to Song dynasty ink painting. Famous Southern Song dynasty painters such as Ma Yuan and Xia Gui employed asymmetrical composition, expansive blankness, and limited pictorial elements, often summarised as “Ma’s corner” (马一角) and “Xia’s half-side” (夏半边) to construct an open yet restrained emotional field.

Paintings by the literati similarly prioritised the expressive rhythm of brushwork over representational fidelity. Meaning, in these traditions, emerges not from saturation or completeness, but from the tension between presence and absence.

These aesthetics can be found as a contemporary visual strategy rather than a stylistic inheritance in The Legend of Hei. High frame counts, restrained linework and fluid hand-drawn motion foreground the temporal nature of 2D animation, allowing emotion to unfold through rhythm and pause rather than spectacle.

This restraint shapes the narrative: conflicts are deferred, positions withheld and characters emerge through hesitation and subtle gestures. In The Legend of Hei 2, such visual openness absorbs contemporary tensions — anxiety, uncertainty and latent opposition — and turns negative space into a way of enduring pressure rather than resolving it. Like many other independent animators who upload their works to Bilibili and YouTube, restraint becomes an ethical choice and an attitude of creation: remaining present within conflict, without reducing it to spectacle.

Rather than focusing on a single heroic figure, the series adopts an ensemble structure, similar to Chinese handscroll paintings such as Along the River During the Qingming Festival, where attention shifts across characters of different roles and social hierarchies within a shared social world.

From myth to reality: de-heroicisation as narrative strategy

Chinese animation has long operated under the pull of mythological storytelling. Yet tradition alone does not guarantee contemporary relevance. What matters today is not the repetition of mythic archetypes, but the selective process through which values are retained, revised, or discarded.

Although The Legend of Hei also takes place in a world where humans and spirits coexist, myth serves less as moral authority than as narrative scaffolding. Rather than focusing on a single heroic figure, the series adopts an ensemble structure, similar to Chinese handscroll paintings such as Along the River During the Qingming Festival, where attention shifts across characters of different roles and social hierarchies within a shared social world.

By tracing intersecting relationships — between adult and child, human and spirit, the powerful and the vulnerable — it shifts focus away from Xiaohei’s individual adventure toward how individuals encounter one another within asymmetrical systems. This de-heroicised orientation resists moral absolutism and narrative closure, allowing compromise and contradiction to remain as enduring conditions of coexistence.

This stance is articulated clearly in The Legend of Hei. When Xiaohei asks his mentor Wuxian whether the villain Fengxi is a “bad person”, Wuxian replies: “No need to ask me — you can have your own answer.” This refusal to dictate moral conclusions distinguishes the series from heroic epics or mytho-national narratives that promise clarity and closure. Instead, it reflects an East Asian social sensibility of acute attentiveness to conflict within dense relational networks, coupled with deep caution toward definitive solutions.

... the film reflects a Chinese-informed management perspective: achieving coexistence requires not only prudence and restraint but also the proactive responsibility of the strong to guide situations toward stability and balance.

In The Legend of Hei 2, the ideal that the strong and the weak may coexist is most clearly illustrated in the conversation between Yu Di, the chief of the Spirit Association, and Elder Ling Yao. When conflicts arise between the Spirit Association and human interests, although the spirits have the power to defeat humans, Yu Di does not resort to war or retaliation. Instead, he takes a broader view but with lots of flexibility, proactively coordinating with human leaders, actively participating in investigations, and emphasising that “coexistence with humans is the future”. He highlights that humans have forged new paths through technology, and the Spirit Association must engage actively to ensure that no one is left behind.

Through this dialogue, the film reflects a Chinese-informed management perspective: achieving coexistence requires not only prudence and restraint but also the proactive responsibility of the strong to guide situations toward stability and balance. This rational and tempered approach protects the vulnerable and maintains relationships while avoiding extreme confrontation and ideological rigidity, underscoring the importance of sustaining ethical relations within the complexities of contemporary Chinese society.

Female subjectivity: from functionality to agency

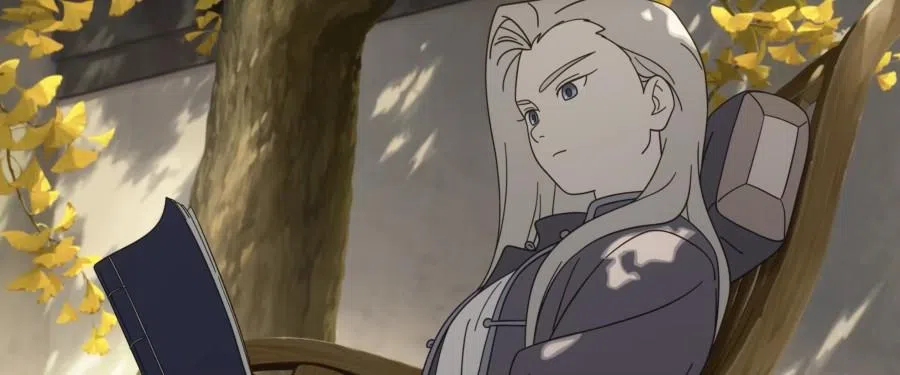

In the world of The Legend of Hei, gender is vaguely emphasised. The character of Luye constitutes a crucial emotional and ethical anchor within the film. She does not conform to the increasingly popular formula of the “revenge-driven strong female protagonist”, a narrative structure that relies on suppression followed by cathartic release and often remains, at its core, invested in the spectacle of human desire for violence and retribution. Luye is neither defined by overwhelming power nor reduced to a symbolic function. Instead, she exists as an agent who repeatedly makes concrete choices within layered and unresolved conflicts.

Luye offers a model of heroism that departs from conventional narratives based on power, identity or domination. Her subjectivity does not stem from her status as a spirit or from physical strength, but from her capacity for judgement, responsibility and response within specific situations. She continually negotiates between institutional order and personal conviction, assuming the consequences of her choices.

Her strength is articulated not through moral superiority, but through persistence after trauma — through care, attachment and the decision to sustain relationships in the aftermath of war. This form of relational endurance constitutes a grounded and credible power. Importantly, Luye is also allowed vulnerability: she requires care even as she offers protection. By refusing to separate strength from softness, her characterisation resists binary representations of female agency and instead reflects a form of subjectivity shaped gradually through conscious, restrained choices within inherited structures.

As a young Asian woman, Luye’s characterisation has led me to reconsider subjectivity as something that does not necessarily presuppose a feminist “victory” or a completed state of emancipation, but rather as a process continually negotiated within unstable and constrained realities.

... the forms of care, vulnerability, and relational persistence embodied by Luye resonate more closely with my lived experience and offer an alternative model of female subjectivity that does not rely on value assimilation.

In my experience, many social and professional structures continue to default to masculine values. The Japanese term “honorary man” (名誉男性, meiyo dansei) captures this paradox with particular precision, as it describes women who have aligned themselves with masculine value systems and earned their place as “one of the boys”. Within such contexts, if women are required to emulate or internalise male-dominated norms in order to be recognised as successful, such success can hardly be understood as genuine strength.

By contrast, the forms of care, vulnerability, and relational persistence embodied by Luye resonate more closely with my lived experience and offer an alternative model of female subjectivity that does not rely on value assimilation. Moreover, her characterisation also disrupts rigid gender allocations of affect: care and vulnerability are not exclusively feminine attributes, nor are men exempt from the need for tenderness and emotional exposure. In this sense, Luye makes visible a mode of female agency that does not depend on heroic or masculinised narratives of empowerment.

Another path toward the world

The Legend of Hei is emotionally grounded in an East Asian context, shaped by anxieties over identity, heightened sensitivity to conflict, opposition to war and a sustained hope for coexistence. Rather than asserting its significance through grand narratives or declarative gestures, the film communicates through restraint and sincerity, allowing its affective force to resonate across cultural boundaries.

I am drawn to The Legend of Hei precisely because of this restraint and gentleness. In a work that refuses to speak loudly or to stand for any singular ideology or imagined future, I find a rare sense of ease and recognition. Although the film is not without compromise, it consistently avoids becoming a vehicle for industrial spectacle or value projection. Instead, it reflects the collective efforts of a generation of young Chinese creators who continue to pose questions within a cultural discourse that still belongs to them.

As a viewer who has grown up alongside Hei, I find the human touch of 2D animation and its capacity for individual community layered storytelling especially precious, especially in China’s context. The ability to locate one’s own mode of survival and expression within narrative and material constraints is, in itself, a vital form of creative life. In this sense, The Legend of Hei points toward another possible future for Chinese animation: with the values we hold, we can gradually form a more inclusive and deeply resonant emotional language that can move across linguistic boundaries.

Of course, Hei represents only the visible tip of a much larger creative community. Across China, countless creators come together through shared passion and affinity. These connections are not founded on promises of victory or fame, but on a shared commitment to remain with the world — gently and persistently — within the complexities of history and the present. It is precisely through this refusal to equate value with triumph that a more durable and profound cultural vitality can emerge.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)