The spread of anti-Semitism on Chinese social media

Historically a refuge for Jews, China is now seeing rising online criticism of Israeli Jews, especially since the 7 October Hamas attack. Middle East Institute-NUS research fellow Jing Lin explores this phenomenon.

On 27 January, the world solemnly observed International Holocaust Remembrance Day, commemorating the six million Jewish lives lost to one of history’s greatest atrocities. Leaders and communities across nations reaffirmed their commitment to combating anti-Semitism. Meanwhile, China’s ambassador to Israel, Xiao Junzheng, recently published two articles in Israel’s largest Hebrew-language newspaper titled “33 Years of Sincere Friendship” and “Sino-Israeli Cooperation for the Benefit of the Two Peoples”, emphasising that China has no soil for anti-Semitism and that the Chinese government will not allow its existence or development.

Xiao wrote that the Chinese and Jewish peoples stood by each other during World War II, and that the traditional friendship between China and Israel, and between the Chinese and Jewish people has endured the test of history and remains strong over time. As 2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the World Anti-Fascist War, it’s pertinent to examine whether anti-Semitism has found fertile ground in China.

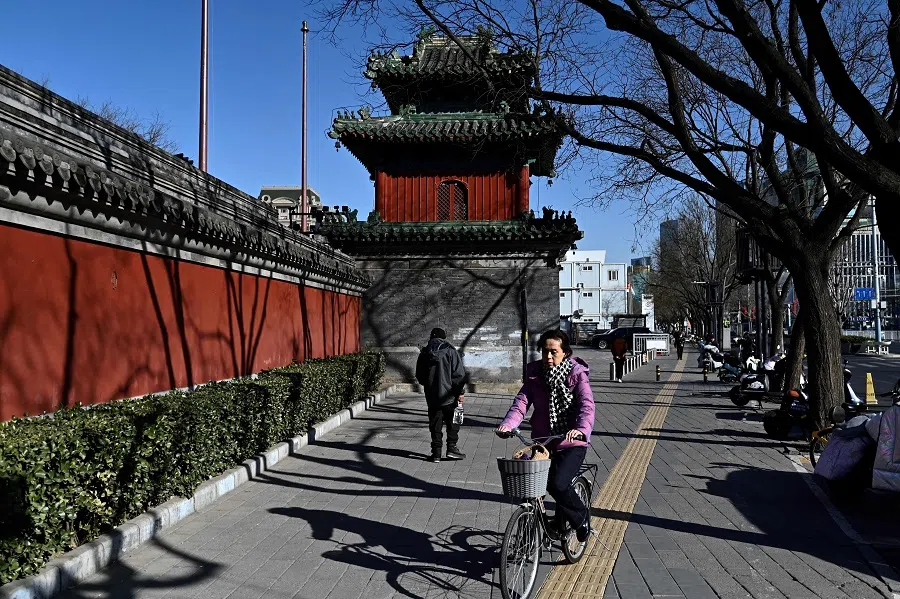

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Harbin became home to one of the largest and most vibrant Jewish communities in East Asia.

China a historical place of refuge for Jews

Historically, China has been a place of refuge for Jewish communities, distinguished from the deeply ingrained anti-Semitic attitudes of Europe and the Middle East. Jewish presence in China dates back to at least the Tang dynasty, with the most well-documented case being the Jewish community in Kaifeng, which settled during the Song dynasty. Unlike in Europe, where Jews faced systemic persecution, Kaifeng’s Jews were allowed to maintain their religious traditions and gradually assimilated into Chinese society.

In modern history, tens of thousands of Jews found sanctuary in China. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Harbin became home to one of the largest and most vibrant Jewish communities in East Asia. Many of its Jewish residents were Russian Ashkenazi Jews who fled pogroms, political upheaval and the Russian Revolution. By the 1920s and 1930s, Harbin’s Jewish population reached around 20,000, forming a thriving cultural and economic hub.

Although most Jews left China after World War II and the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Harbin’s Jewish heritage remains evident in historical sites such as the Harbin Jewish Cemetery and the former synagogue, now a museum preserving the city’s Jewish legacy.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Shanghai became one of the few places in the world to welcome Jewish refugees during World War II, providing a shelter for tens of thousands fleeing Nazi persecution. Figures such as Ho Feng-Shan, the Chinese diplomat who issued thousands of visas to Jewish refugees in Vienna, and Pan Jun-Shun, who helped a Jewish girl hide from the Nazis and saved her life in the Ukrainian SSR, exemplify Chinese sympathy towards Jews. Their humanitarian efforts earned them the title of “Righteous Among the Nations” from Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial.

The former Jewish residents of China established the Israel-China Friendship Society (ICFS) and the Association of Former Residents of China in Israel (FRCA). They organise annual reunions, cultural events and educational programmes to strengthen ties between former Jewish residents and China, also collaborating with Chinese institutions to document Jewish heritage and promote historical awareness.

Chinese academic interest in Jewish history has grown

Beyond historical ties, China has shown scholarly interest in Jewish history and culture. Jewish studies as an academic discipline have grown in China, with researchers examining Jewish philosophy, history and identity from comparative perspectives.

Since China’s reform and opening up, and especially after the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Israel in 1992, Jewish studies have flourished in China. The country saw the emergence of its first Jewish research institutions, including Jewish Studies Centres at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences (1988) at Nanjing University (1992) and Shandong University (1994). Scholars such as Pan Guang, Xu Xin, Fu Youde and Xiao Xian were pioneers in the field.

In recent years and especially following the 7 October Hamas attack and the subsequent Israel-Gaza war, Chinese social media has seen a surge in public criticism regarding the Israeli Jews.

In 2015, with support from the Chinese Ministry of Education, seven universities established the China Alliance for Jewish Cultural Studies to further promote research in this field. Chinese scholars have long been committed to the study and education of Jewish history and culture, striving for an accurate understanding of the Jewish people and their traditions.

However, among the general public, there still exists a problematic fascination — stereotypes of Jews as being uniquely intelligent and financially adept. While often expressed as admiration, such stereotypes can easily transform into resentment, particularly during periods of political tension. What has surprised and disappointed many within China’s Jewish studies academia is that, almost suddenly, China has found itself facing accusations of anti-Semitism due to the surge of radical rhetoric on social media.

Recent perception of rising Chinese anti-Semitism

In recent years and especially following the 7 October Hamas attack and the subsequent Israel-Gaza war, Chinese social media has seen a surge in public criticism regarding the Israeli Jews. In both a November 2023 interview with Voice of America and a speech on 23 January 2025 for International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Israel’s ambassador to China Irit Ben-Abba noted an increase in “anti-Semitic” rhetoric on the Chinese internet since the 7 October conflict.

However, the definition of anti-Semitism — particularly its scope and application — has been a contentious issue. The US Antisemitism Awareness Act, passed in May 2024, adopts the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) definition, which some argue conflates legitimate criticism of Israeli government actions with anti-Semitism.

Anti-Zionist sentiment is common worldwide in discussions of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, especially in the wake of military escalations in Gaza, much of it remains rooted in concerns over issues like occupation, human rights violations, and military aggression. In this context, it is essential to objectively analyse the motivations behind such rhetoric and preserve the space for critical discussions about international politics, without mislabelling all dissent as anti-Semitic hate speech.

Some narratives accuse Jews of manipulating world affairs, leveraging their supposed financial dominance, or being responsible for global conflicts. Such discourse is largely parroted from imported narratives...

A blurring of lines in the online world

That said, it must be acknowledged that some of the radical discourse does cross into anti-Semitic territory. In certain cases, China’s online rhetoric has blurred the line between legitimate criticism of Israel and outright hostility toward Jews as a collective.

Users have circulated conspiracy theories reminiscent of Western anti-Semitic tropes — claims that Jews control global finance, Western governments, and even Chinese industries. Some narratives accuse Jews of manipulating world affairs, leveraging their supposed financial dominance, or being responsible for global conflicts. Such discourse is largely parroted from imported narratives. China historically lacked accusations against Jews regarding the death of Christ — an idea rejected by modern theology — or scapegoating them for economic woes. However, in the digital age, ideological boundaries are porous. Conspiratorial ideas travel easily across linguistic and cultural divides, finding new audiences in unexpected places.

To understand why anti-Semitic rhetoric has gained traction in China, the insights of Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind may help. Le Bon argued that crowds, whether physical or virtual, behave in ways that individuals do not. In a crowd, rationality is diminished, emotions run high, and individuals are more susceptible to suggestion. The sheer volume of Chinese social media posts has created an environment where misinformation and emotional responses spread rapidly.

Chinese netizens, largely isolated from international Jewish communities and reliant on state-controlled narratives about world affairs, often lack firsthand knowledge of Jewish history and identity. This makes them particularly vulnerable to sensational narratives that frame Jews as a shadowy, controlling force in global politics.

Le Bon also emphasised the role of anonymity in crowd behaviour. When individuals feel anonymous, they are more likely to express extreme views without fear of consequences. In China’s digital landscape, where censorship is strict on politically sensitive domestic topics, discussions of international affairs — including Israel and Jewish issues — offer a relatively open space for more radical or conspiratorial viewpoints.

The emotional nature of online discourse amplifies anger and resentment, and outrage-driven algorithms ensure that inflammatory content — whether anti-Semitic or otherwise — gains disproportionate visibility. As online trends shift and new topics capture public attention, such expressions may diminish over time, fading like a passing tornado.

The perception of Jews as a powerful, Western-aligned group controlling finance and politics fits into an already prevalent nationalist narrative of Western influence over China.

Geopolitics sets the stage

Moreover, the current geopolitical climate has contributed to this surge. In China, opposition to the West has intensified in recent years, with official rhetoric emphasising US hegemony and Western imperialism. Since Israel is seen as an ally of the US, some have projected their anti-Western sentiment onto Jews as a whole. The perception of Jews as a powerful, Western-aligned group controlling finance and politics fits into an already prevalent nationalist narrative of Western influence over China. While such rhetoric may not originate from state actors, regulators have been slow to counter it, allowing it to spread unchecked.

Despite this rise in online anti-Semitism, China remains fundamentally different from societies where anti-Semitism is deeply entrenched. There are no historical pogroms, no history of Jewish expulsions, and no institutionalised discrimination against Jews. Instead, anti-Semitic rhetoric in China today is a product of modern information flows, social media crowd psychology, and geopolitical realignments rather than historical prejudice.

However, this lack of historical awareness also means that many Chinese netizens may not fully understand the implications of anti-Semitic rhetoric. Without a historical framework for recognising anti-Semitism, some individuals may inadvertently adopt these narratives, viewing them as mere critiques of global capitalism rather than as dangerous prejudices.

Just as China takes pride in its history of protecting Jewish refugees, it must recognise the importance of resisting the spread of bigoted ideologies that have caused devastation elsewhere, and that the digital age requires a renewed commitment to preserving its legacy of tolerance.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)