[Video] Ethnic Chinese new villages: Malaysia’s hidden heritage or controversial legacy?

Malaysia’s ethnic Chinese new villages, born from colonial control against the communists, face decline amid ageing and migration. Yet revitalisation efforts through tourism and community initiatives offer hope, sparking debate over their cultural value and potential UNESCO heritage status. Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Seoow Juin Yee speaks to residents and community leaders to find out more.

(Photos by Hugo Teng, except otherwise stated)

“This place has become a city, it’s no longer a new village. The young people do come back. During the new year or other festivals such as Qing Ming, it’s more lively. Usually it’s very quiet.”

84-year-old Wan Bok Lam grew up in Selangor’s Sungai Way New Village. He used to run a tze char stall with his father, and has witnessed the ups and downs of the place.

Changing faces of new villages

Wan recalled, “In the old days, this was a village where the Hainanese congregated. At first, there were only six families, with rubber plantations all around. We used to call this place Hainan Village. Now it’s Sungai Way, with people of various dialect groups and ethnicities.”

Located in the bustling urban area of Petaling Jaya, Sungai Way has managed to preserve its culture and characteristics, and is known as a unique new village hidden in the city. The area used to be famous for its tin mines and rubber plantations — in the 1970s, it was developed into a free trade industrial zone, and Sungei Way became the first urbanised new village in Selangor.

Fifty years on, many Chinese new villages in Malaysia have been gradually hollowed out by urbanisation. Many young residents have moved away into modern terraced houses with their elderly parents, while their former residences have been leased out to migrant workers from other parts of Malaysia or foreign labourers.

To isolate the MCP [Malayan Communist Party] from the local Chinese, retired British general Harold Rawdon Briggs devised a plan to relocate ethnic Chinese farmers living near the jungle into concentrated settlements.

But some residents are actively revitalising new villages, to preserve the shared memories of several generations.

The villagers of Sungai Way have contributed everyday items and keepsakes to be displayed at the Korridor Serajah museum, set up in 2021, to preserve family history and in the hope the museum will be a check-in spot for tourists. The village also holds various activities during festive periods, with villagers working together to beautify it to attract more tourists.

Colonial origins: new villages as control mechanisms

The history of new villages goes back to the post-World War II era. In 1948, under threat from the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), the British colonial government declared a state of emergency in the Federation of Malaya.

To isolate the MCP from the local Chinese, retired British general Harold Rawdon Briggs devised a plan to relocate ethnic Chinese farmers living near the jungle into concentrated settlements.

Dr Ho Kee Chye, who heads the Chinese Studies Department at the University of Malaya (UM), said: “The colonial government figured that the best way to deal with the MCP was to move the settlers into one place. That way, the MCP wouldn’t be able to get food, medicine, or information while hiding out in the jungle.”

This large-scale operation was called the Briggs Plan, and the concentration camps evolved into “new villages”. In the Malay Peninsula, where the MCP was active, over 400 new villages sprang up within a few years.

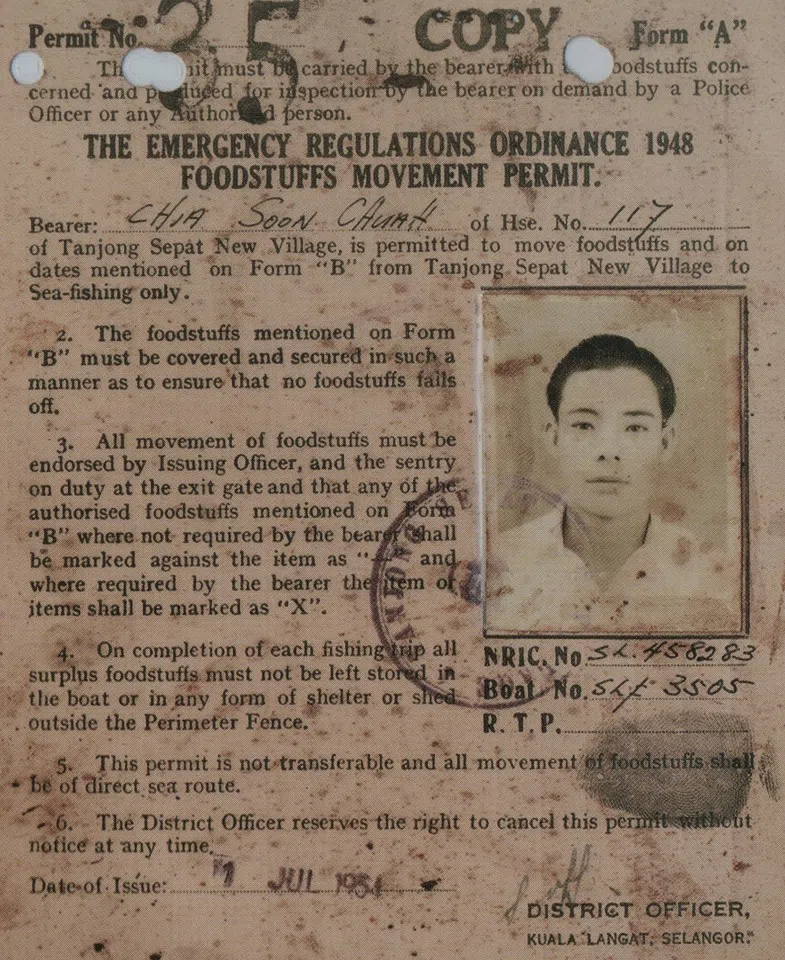

The early new villages were surrounded by metal fences, with watch towers and access points guarded by the military police. Villagers had to register their movements in and out, and there was a curfew.

The early new villages were surrounded by metal fences, with watch towers and access points guarded by the military police. Villagers had to register their movements in and out, and there was a curfew.

From ‘concentraion camps’ to home

85-year-old Lim Peng Chow still remembers how, 70 years ago, he and his family got on a lorry with their simple belongings and moved to Sungai Way. “The road had an iron gate and barbed-wire fences. Police were stationed there. You needed a permit to go anywhere, and we had to use tokens to buy rice.”

Sungai Way was a model for the new villages initiative. In 1953, then US Vice-President Richard Nixon visited Malaya and specially made a stop here. The Korean War had just ended and the Vietnam War was a hair-trigger away. Nixon’s trip was to find out how Malaysia was implementing the new village plan to fend off the communist threat.

Later, the government gradually improved the infrastructure in the new villages, including providing running water and electricity, and setting up schools and community halls, as the community gradually formed.

Dr Ho said: “The government tried to create a better living environment so people wouldn’t think they were concentration or detention camps. They also wanted to encourage more ethnic Chinese in the border areas and other areas to willingly move into these new villages.”

After the state of emergency was lifted in 1960, there were no more guards or rationing in new villages and the fences were torn down, but the new villages were not scrapped or dissolved, because for many people, it was home.

In 1954, there were 570,000 Chinese living in new villages, about one-fifth of the local ethnic Chinese population in Malaysia; with population growth in the new villages, the figure reached 1.65 million in 1985.

Outflow of young people due to urbanisation

By the late 1980s, the population in new villages started to fall, with some remote villages more severely affected as young people left for the cities. By 2002, the population of new villages was 1.25 million, and according to the latest estimate, the figure is currently about one million.

Dr Ho analysed that new villages in the 1980s lacked institutional support and government funding, while infrastructure was lagging and job opportunities were limited, with low education levels. All this led many young people to move to the cities.

Issues with long-term development and social problems also began to surface, including disputes over property ownership, youths dropping out of school, gang activity, and sanitation issues.

When I visited, I noticed that it was mostly the elderly and children who remained in the new village.

Sungai Way once prospered due to the nearby free trade industrial area, but with an ageing population and emigration, old dwellings are now rented to foreign workers in nearby factories, numbering over 10,000 at one point. Today, the number of ethnic Chinese residents has plummeted to about 3,000.

Village head Ding Eow Chai sighed: “In the 1980s, the new village was very lively and full of warmth. Now, the population has aged significantly. Our primary school used to have more than 1,000 students, now there are only five to six hundred.”

When I visited, I noticed that it was mostly the elderly and children who remained in the new village. Traditional brick and wood dwellings are now rare, mostly replaced by modern houses, so the village looks different from before.

Malaysia’s Chinese urban roots

The establishment of new villages led to the resettlement of up to a million people, changing their lives and rearranging the distribution of ethnic Chinese people in Malaysia.

By the time the new village policy came to an end, the structure of ethnic Chinese settlements had largely been established. Many of these new villages were eventually absorbed into towns and cities, which helps explain why a large proportion of ethnic Chinese Malaysians are concentrated in urban areas today.

As Dr Ho noted: “Although some of these towns may seem to be in decline now, the new village policy at the time gradually moved Chinese communities closer to urban centres, accelerating their urbanisation.”

In 2009, the Malaysian government also classified some resettlement villages and fishing villages as new villages. According to the latest statistics, there are 613 new villages in Peninsular Malaysia, including 436 traditional new villages, 134 resettlement villages and 43 fishing villages. Resettlement villages refer to ethnic Chinese communities relocated to the outskirts of cities or the peripheral areas under local government administration.

Located in the northwestern part of Selangor, Sekinchan is renowned for its rice production and seafood, and is known as the “Land of Fish and Rice”. The town includes three resettlement villages and one fishing village.

Sekinchan’s revival: tourism breathing new life

Although many new villages gradually declined due to their remote locations and underdeveloped infrastructure, some have been revitalised through tourism and other economic activities. Sekinchan in Selangor is one example of a successful transformation.

Located in the northwestern part of Selangor, Sekinchan is renowned for its rice production and seafood, and is known as the “Land of Fish and Rice”. The town includes three resettlement villages and one fishing village.

Despite its thriving fishing and agricultural sectors, Sekinchan has not escaped the challenges of an ageing population and outward migration. However, thanks to media promotion and the active efforts of the local community, Sekinchan became one of the first new villages to embark on community revitalisation and tourism development.

Ng Suee Lim, Member of the Selangor State Legislative Assembly for Sekinchan, said since 2008, the local government and villagers began promoting Sekinchan’s natural scenery and unique features through the internet and other channels.

In 2012, Malaysian and Singaporean television stations jointly filmed the drama series The Seeds of Life (渔米人家) in Sekinchan, which brought the town instant fame. “During holidays and weekends, tourists flock here, and many visitors come from Singapore as well. I encourage local entrepreneurs to build homestays and set up rice mills, so that everyone can work together to develop the tourism industry.”

Ng is also Selangor’s executive councillor in charge of local government, tourism, and New Village development, giving him access to resources to support tourism growth in these communities.

Sekinchan’s tourism boom has not only attracted large numbers of visitors but also encouraged many young people to return home to start businesses such as cafés, homestays, and local specialty shops.

New village’s returning resident: Alan Heng

Alan Heng, who grew up in Sekinchan, previously organised cultural and creative activities in the town before moving to Kuala Lumpur to work in advertising. During the Covid-19 pandemic, he shut down his advertising company and returned home in search of new opportunities.

Drawing on his advertising experience, Heng began promoting Sekinchan’s seafood online, selling the town’s marine products across Peninsular Malaysia. This created a new path for the traditional fishing industry through e-commerce.

Sekinchan’s successful transformation owes not only to its favourable geographical conditions but also to the community’s deep understanding of local characteristics and their collective efforts in promotion. Today, rice cultivation, fisheries, and tourism have become Sekinchan’s three economic pillars.

“Each place has its own DNA and uniqueness. The key lies in whether the locals can recognise the special qualities of the land beneath their feet.” — Alan Heng, a Sekinchan resident

Heng believes that each new village holds unique potential waiting to be discovered. “Each place has its own DNA and uniqueness. The key lies in whether the locals can recognise the special qualities of the land beneath their feet.”

After the Selangor government changed in 2008, efforts to revitalise new villages gained momentum. The Pakatan Rakyat coalition (the predecessor of Pakatan Harapan) formed committees to fulfil election promises, funding reading clubs, cultural projects and tourism initiatives like “New Village-ing” and Kampung GOOD to reconnect the public with village life. Khoo Poay Tiong, chairman of the Malaysia New Villages Development Committee, said Kampung GOOD helps bring village food, culture, and products to market, boosting the local economy and incomes.

Following the change of federal government in 2018, the Pakatan Harapan administration became even more proactive in new village development. In 2022, the ruling Unity Government allocated RM100 million (approximately US$23.7 million) annually for infrastructure and environmental upgrades, along with a ten-year blueprint to support promising villages.

Balancing progress with heritage

The Covid-19 pandemic unexpectedly became a turning point for new villages. With overseas travel restricted, more people turned to exploring domestic tourism more thoroughly. Leveraging their unique living environments and cultural memories, new villages emerged as popular new travel destinations.

During the pandemic, some young people also began to reassess their pace of life and chose to return to their hometowns. The widespread use of digital technology further fueled this trend.

“Life in the city is fast-paced and stressful. Increasingly, young people are considering returning to new villages to build their future. They open homestays and organise experiential activities, allowing urban visitors to personally enjoy rural life.” — Khoo Poay Tiong, Chairman, Malaysia New Villages Development Committee

Khoo Poay Tiong noted: “Life in the city is fast-paced and stressful. Increasingly, young people are considering returning to new villages to build their future. They open homestays and organise experiential activities, allowing urban visitors to personally enjoy rural life.”

After several years of transformation and community revitalisation initiatives, some aging new villages have found new vitality. For example, Kuala Sepetang in Taiping, Perak, is famous for its mangroves, while the new villages around Bentong in Pahang attract food lovers with their abundance of durians.

Dr Ho believes the potential of new villages has yet to be fully tapped. “The revitalisation of Malaysia’s new villages is still at an early stage. There remains huge room for improvement and innovation, and the outlook is promising.”

Khoo emphasised that new village development should strive to preserve their original character and distinctive charm, progressing steadily in harmony with the local environment and community economy. “As development advances, some new villages may inevitably give way to new planning. We must find the balance between growth and preservation.”

UNESCO nomination sparks heated debate

Malaysia’s ethnic Chinese community believes that new villages hold unique historical and cultural value, and should be preserved and protected. However, in a multi-ethnic society, efforts by the ethnic Chinese community to safeguard this collective memory and promote the development of new villages involves many challenges.

In the 1990s, new villages encountered difficulties due to political factors. The Sixth Malaysia Plan in 1992 did not allocate clear funding for new villages. Authorities even removed the term “New Village” (Kampung Baru) from the names of some settlements, replacing it with politically neutral terms such as Kampung, Seri, Jaya, or Desa. The aim was to rebrand new villages as ordinary villages or suburban areas, making it easier for them to apply for government funding.

For example, Sungai Way New Village was renamed Seri Setia a long time ago, but people still know it better by its old name.

Today, new villages may no longer struggle with funding allocation, but they continue to face other challenges.

The move, however, drew strong opposition from UMNO members within the Unity Government, opposition parties, Malay NGOs and some scholars, who argued that such recognition would undermine Malay rights and status.

In 2023, the Unity Government proposed to nominate seven new villages nationwide for UNESCO World Cultural Heritage status. The move, however, drew strong opposition from UMNO members within the Unity Government, opposition parties, Malay NGOs and some scholars, who argued that such recognition would undermine Malay rights and status.

UMNO’s stance on the matter remains ambiguous. When UMNO governed Terengganu in 2016, then Menteri Besar Ahmad Razif had in fact suggested nominating new villages in the state for heritage status.

Divided opinions: pride or dark history?

Some scholars argue that new villages are not a legacy to be proud of.

Emeritus Professor Teo Kok Seong from the National University of Malaysia Institute of Ethnic Studies described new villages as “a dark chapter in the nation’s history”, with no glorious influence to speak of. In his view, Malaysians should not feel proud of their existence but rather learn lessons from them and allow them to pass into history.

Khoo Poay Tiong stressed that Malaysian society should take a broader perspective in evaluating the UNESCO heritage nomination. He cited the examples of Malacca and Penang, where heritage listing spurred rapid tourism growth. “If some new villages gain heritage status, it would not only benefit their development but also boost the economy of the surrounding areas.”

Malaysian society remains divided over whether new villages should be nominated for UNESCO recognition. On 6 August this year, Tourism, Arts and Culture minister Tiong King Sing told Parliament that the government had yet to decide whether to seek UNESCO heritage status for new villages, or to designate them as national heritage sites instead.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “居民老龄化加空心化 马华人新村转型求存”.