From worms to theology: Scientist Samuel Gan’s quest to decipher the world

Professor Samuel Gan, a Singaporean multi-disciplinary researcher and academic at Wenzhou-Kean University in China, explores everything from plastic-eating worms to theology. Lianhe Zaobao senior correspondent Poh Lay Hoon reports on this dynamic, unstoppable academic.

Even before meeting Professor Samuel Gan, I feel a little breathless just reading about him.

He is impatient by nature — he watches shows speeded up on his phone and earned seven academic qualifications (bachelor’s and post-graduate degrees, master’s and doctorate) in seven years. It seems he has never taken a break in his life, as he efficiently makes use of each moment.

Not only does Gan drive himself hard, he does the same to the worms he is studying as he keeps pushing them to be faster. Despite these “poor” worms consuming plastic waste at double, then seven times normal speed, he is still not satisfied, and wants to raise it to ten times the normal speed through further experimentation and optimisation.

At 43, Gan is known for his rigorous intellect and relentless drive for breakthroughs, constantly pushing toward new frontiers.

Gan is single and an only child. His mother, a homemaker born in Taiwan, and his father, a retired tour guide, are both in their 70s. Gan attended St. Stephen’s School and St. Patrick’s School for his primary and secondary education before earning a biotechnology diploma from Temasek Polytechnic (TP).

A lost opportunity

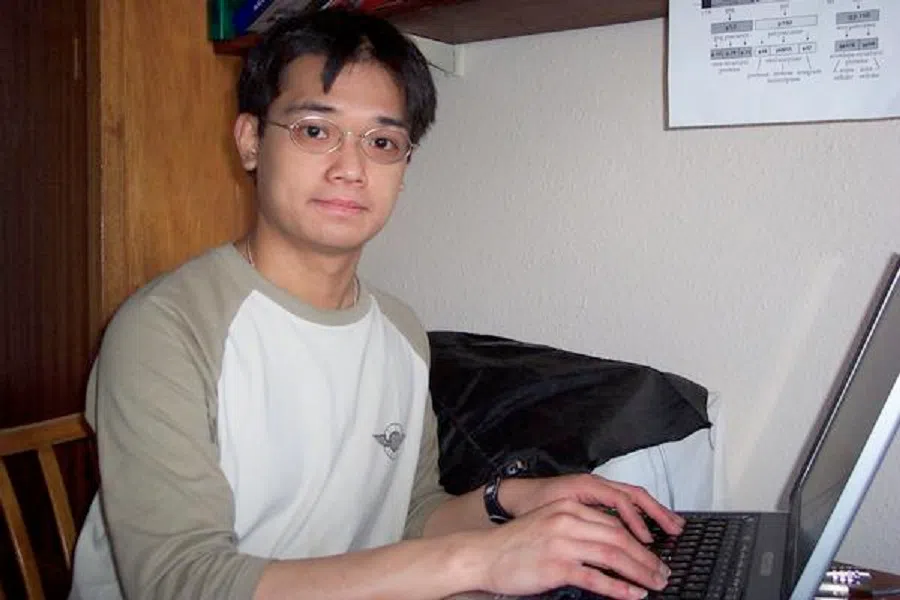

In 2001, the 19-year-old Gan became the first final year student of the TP biotechnology diploma to have a research paper published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

In 2003, Gan was serving his national service as a healthcare assistant when he jointly published a clinical study in a medical journal as first author with two doctors on hypertension among national servicemen in the Singapore Medical Journal.

His outstanding research outcomes earned him advanced placement offers from numerous overseas universities. He ultimately chose to pursue an honours degree in molecular cell biology at University College London (UCL), becoming the first Singaporean polytechnic graduate admitted directly into UCL’s second year of undergraduate studies.

Gan recalled even suggesting to the agencies that giving him a scholarship would save them money since he was starting in his second year. “But they didn’t buy it,” he said.

In a 2004 Lianhe Zaobao article about national servicemen hypertension research, the two other doctors involved praised Gan, calling him a very promising scientist.

At that time, Gan was studying in London. He told Zaobao in an email interview that he regretted not getting a scholarship from A*STAR and the Defence Science and Technology Agency (DSTA). A*STAR said his SAT score was below expectations, while DSTA did not award scholarships to polytechnic graduates then. In 2004, DSTA changed its approach and started giving out scholarships to polytechnic graduates.

Gan recalled even suggesting to the agencies that giving him a scholarship would save them money since he was starting in his second year. “But they didn’t buy it,” he said.

“It was a blessing in disguise. What seemed bad at the time, God turned into something good.”

Gan only took two years to obtain his first degree, during which he worked three jobs including being a translator/interpreter, tutor, and university teaching assistant, saving his parents a lot of money.

Being an asthmatic, Gan decided to study allergy. Since there was no such specialty offered locally, he headed to the UK on his “parents’ scholarship”.

Working three jobs and graduating within two years

Gan only took two years to obtain his first degree, during which he worked three jobs including being a translator/interpreter, tutor, and university teaching assistant, saving his parents a lot of money. For his PhD studies, he relied on a scholarship from the university.

In 2005, Gan obtained his molecular cell biology bachelor’s degree; in 2007, he got his graduate certificate in academic practice from King’s College London; in 2009, he obtained his PhD in allergy from King’s College London and became an Associate of King’s College, his master’s degree (with merit) in structural biology from Birkbeck College, and bachelor’s degree in psychology from Open University; and in 2010, he received his postgraduate certificate in business administration.

Teaching and researching at Wenzhou-Kean University

On 25 July 2022, Gan flew to Shanghai during the Covid-19 pandemic. After spending ten days in quarantine, he began teaching biology and psychology at Wenzhou-Kean University (WKU, 温州肯恩大学, Wenzhou Kenen Daxue).

Gan’s full name in English is Samuel Gan Ken En, Ken En being the English transliteration of the Hokkien pronunciation of his Chinese name. Coincidentally, Ken En in hanyu pinyin is also part of WKU’s Chinese name. From chancing upon the university’s online recruitment advertisement to successfully becoming a research professor there, it all seemed fated.

In 2020, when the pandemic exacerbated the plastic waste problem, he started looking into the plastic disintegration abilities of superworms and mealworms, and how to use sugar to accelerate the process.

As for why he opted for a joint venture university, he felt that a purely Chinese one would be culturally challenging; he also considered that the teaching materials were all in English.

Gan brought two research projects with him to WKU — worms that break down plastic, and music research. Gan’s “worm project” is interesting and eco-friendly.

In 2020, when the pandemic exacerbated the plastic waste problem, he started looking into the plastic disintegration abilities of superworms and mealworms, and how to use sugar to accelerate the process.

Worms and plastic waste

Gan explained that it originally took one kilogram of worms around 1,000 days to consume 1 kilogram of plastic waste, but he managed to double the rate in 2020. Today, he has increased the speed to seven or eight times the original.

He went on, “We have reduced it from three years to just over three months, and are in the midst of patenting it in China. At the same time, we are studying ways to speed up the process further and hope to achieve a tenfold increase in future. If we succeed, not only can we solve the problem of plastic waste pollution, but the excrement of the worms can also be used as fertiliser, effectively turning waste into treasure.”

Gan emphasised that the method does not involve genetic modification and is highly scalable. He explained, “Many scientists feel that the worms act too slowly and want to speed things up through fermentation, but this creates plenty of waste and results in more problems.

“On the other hand, genetic modifications produce undesirable consequences most of the time. There is also the concern that the worms might escape and pollute the environment. Since the worms are a natural means of fermentation that doesn’t create more waste and with no extra costs, why create more problems for ourselves?

“So, we try to keep it as natural as possible. By optimising the living environment and adding certain supplements, we can make the worms eat faster. The idea is to go back to being perfectly natural, a return to the Garden of Eden instead of creating new products.”

He found that replaying song lists every three or four songs can increase customer turnover. “Subconsciously,” Gan explained, “patrons feel it’s time to leave after hearing the same song five or six times.”

From worms to music

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Gan’s team developed a machine learning model and algorithm for automatically classifying coronavirus antigen rapid test results, as well as a contactless infrared thermometer.

Gan’s research also extends to music. While at A*STAR, he published a report on the effects of background music on customer traffic in restaurants and bars. He found that replaying song lists every three or four songs can increase customer turnover. “Subconsciously,” Gan explained, “patrons feel it’s time to leave after hearing the same song five or six times.”

And if restaurants want to boost sales and get customers to order more food and drinks, the key is to make them feel more comfortable by lowering the music volume as much as possible, because they want to chat.

“I had to completely re-optimise my music project,” he explained. “Singapore favours Western music, but China’s culture and dialects create different musical preferences, requiring complete localisation.

“Unlike shopping centres in Singapore, where one can play music to create a unified soundscape, Chinese shops are more individually segregated, making centralised music distribution difficult.”

Gan has won numerous accolades, including being named one of the “world’s most promising researchers” in the Interstellar Initiative by the New York Academy of Sciences and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, as well as one of the 30 world class fusion innovators featured in the book Innovation Through Fusion by SP Jain School of Global Management. He is also the Bronze winner of the inaugural Merck Lab Connectivity Challenge and recipient of the 2022 British Council UK Alumni Awards in the “Science and Sustainability” category.

Chasing after dreams and research freedom

Gan was attracted by China’s size and its enormous investments in basic research.

In 2022, Gan was offered a three-year contract extension by A*STAR, but after taking into account the differences between the organisation’s direction and his personal aspirations, he decided to head to China instead.

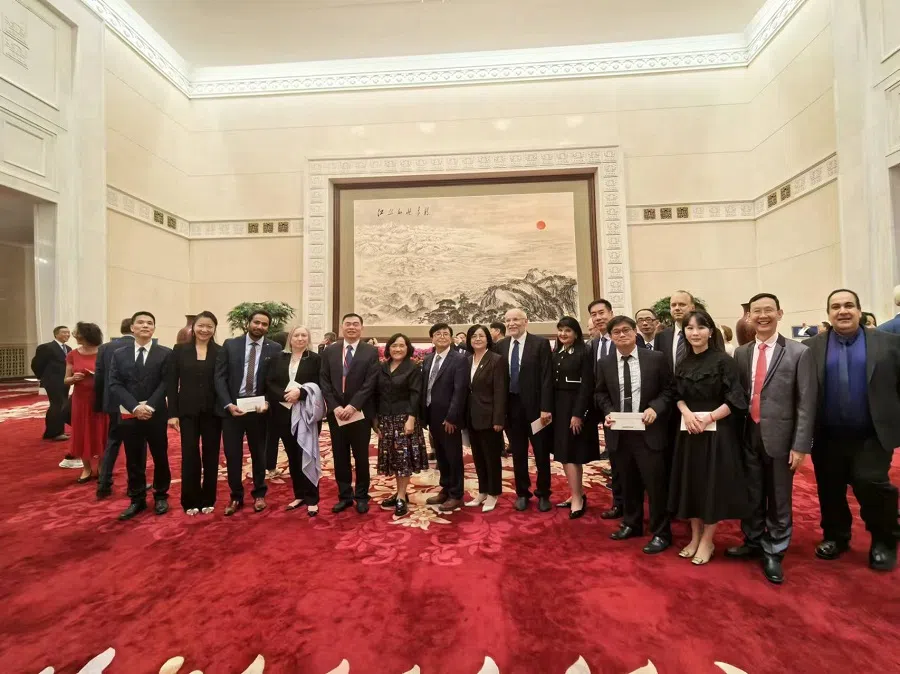

He acknowledged that his decision was influenced by China’s strong appreciation for scientists like him. As a provincial-level talent, Gan received permanent residency from Chinese authorities within just two years.

In 2022, the vice-mayor of Wenzhou, Wang Zhenyong, specially visited WKU to meet with Gan and his team.

“China is a big country with more organisational sponsors. At the same time, it is also more tolerant of different types of research, allowing researchers to focus on a particular domain for 30 to 40 years...” — Professor Samuel Gan, a multi-disciplinary researcher and academic

At the end of September this year, Gan and WKU vice-chancellor, Dr. Eric Yang, represented the university to attend a dinner banquet organised by Ding Xuexiang, vice premier of China and member of the Communist Party of China Politburo Standing Committee, for foreign experts at the Great Hall of the People.

Supportive environment for scientific research

Gan lamented that China attaches huge importance to and is very understanding towards foreign scientists, so he intends to remain there for the long term to contribute his expertise, which is why he accepted Chinese permanent residency.

“China is a big country with more organisational sponsors. At the same time, it is also more tolerant of different types of research, allowing researchers to focus on a particular domain for 30 to 40 years. So, the scientists here can keep working on a particular area instead of facing pressure to change their research direction every five years. It is a very conducive environment for scientific research.”

China’s big domestic market also makes it easier to commercialise research outcomes. Currently, Gan is looking into the commercialisation of worm research and some educational tools he developed in Singapore.

“From a research scientist’s perspective, I consider China my home — a place where I can relax, feel valued, and be my true self. At the Sino-American cooperative university where I currently work, I enjoy the freedom to conduct research I am passionate about and feel a sense of belonging in the realm of science.”

While he offered praise, Gan noted that the dilemma between “theory and practice” exists in both China and Singapore.

“[China’s] overemphasis on academic outcomes neglects application and produces researchers lacking practical experience and adaptability,” he argues. “Researchers need a better balance between theory and application to effectively serve society.”

Giving to society

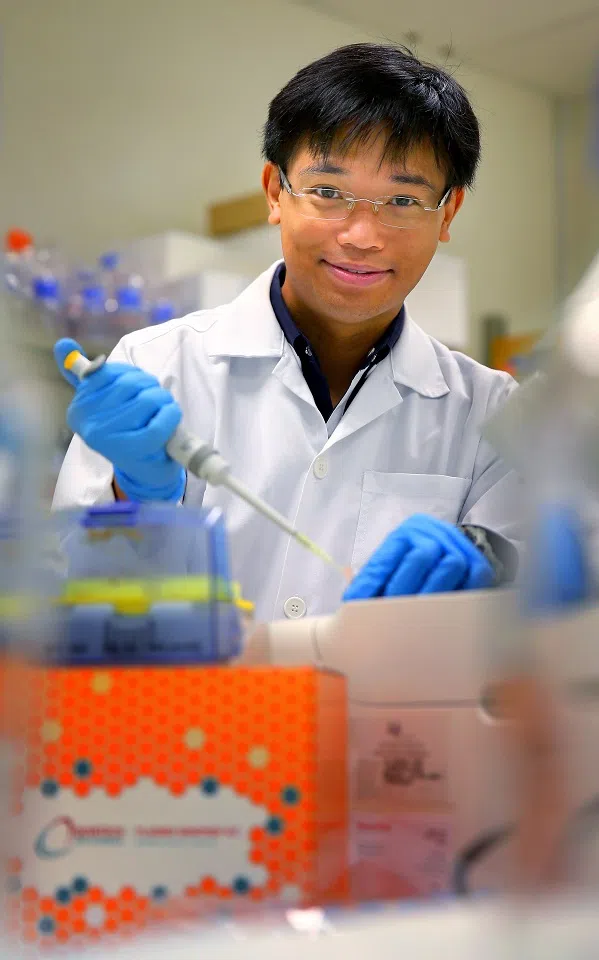

In 2010, Gan started working at A*STAR as an administrator. Three years later, he became the leader of a research team. In 2021, he became the senior principal investigator of its Antibody Product Development Lab. His multidisciplinary research spans antibody engineering and viral drug resistance for targeted drug design.

While Gan is impatient by nature, scientific research often cannot be rushed.

“A*STAR’s KPIs (key performance indicators) require projects to demonstrate impact on society, academia, and technology. Therefore, planning is crucial, and it must include both long-term and short-term plans — like having both slow-cooked dishes and instant noodles.”

In 2017, Gan founded APD SKEG in his alma mater, Temasek Polytechnic. The name is an acronym derived from his initials and those of his work laboratory (Antibody & Product Development Lab).

Rather than profit, Gan’s motivation for founding the company was to create a platform for sparking interest in scientific research and making a positive social impact. The company developed over 50 mobile applications, provided research consulting services and courses, and offered student internships. To Gan, academic research goes beyond publishing papers. “Who’s going to read the papers you published? One should work instead on research that contributes positively and which stimulates the economy.”

After accumulating so much knowledge from books, who would have thought that this super scholar’s biggest regret is not studying theology first?

Gan also encourages students to start their own ventures, such as teaching basic Java and mobile application development courses, to gain experience and help others.

APD SKEG closed last year due to disruptions from the pandemic and Gan’s relocation to Wenzhou. “We managed to break even,” Gan reflects. “Surviving for over five years wasn’t bad.”

Most fascinated by theology

After accumulating so much knowledge from books, who would have thought that this super scholar’s biggest regret is not studying theology first?

“Asians don’t typically value diverse interests,” Gan observes. “Many people think I’m wasting my time and lacking focus.” He laughs, adding, “Ultimately, results matter most. Focus is useless without results, right? So, I need to produce outcomes to prove them wrong!”

Gan constantly optimises his time for maximum efficiency. He works on research papers during long train rides and reads two books concurrently, switching between them when he tires of one. At just 16, while waiting to start at TP, he wrote a science fiction novel. To date, he has authored and contributed to 11 books, including textbooks and individual chapters in other works.

According to Gan, who is a sixth-generation Christian, the English missionary, James Laidlaw, converted his Taiwanese ancestors after arriving in Taiwan. Having spent 11 years attending theology lessons in Mandarin at the Chin Lien Bible Seminary, he is proficient in the language.

Gan feels all subjects originate from theology. In fact, all of Western education is based on Christian beliefs, and the roots of Oxford, Cambridge, Princeton, and Harvard can be traced to churches.

He also pointed out that the beginning of education can be traced to theology. Since theology produced so many different domains, a cross-disciplinary practitioner like him has to know theology in order to integrate knowledge.

Theology has helped him integrate everything

Gan has a reputation as a humorous and supportive teacher who encourages his students’ entrepreneurial aspirations. He often cooks for them and organises trips.

When asked whether he has any regrets, Gan said: “Too many. Academically, I wish I had studied theology first. Christian theology has given me a deeper understanding of life and sparked my deep interest in other disciplines.

“More importantly, theology has helped me to integrate everything I know into a comprehensive system and provided me with a more thorough understanding of the world.” — Gan

“More importantly, theology has helped me to integrate everything I know into a comprehensive system and provided me with a more thorough understanding of the world.”

At the end of the interview, I ask Gan what he is studying at the moment.

“Oh, I am doing my master’s degree in Christian Studies at the Third Millennium Seminary. Theology is my favourite, so I am retracing my path and will not be studying other disciplines anymore.”

Learning never stops. Listening to him, I need to catch my breath.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “跨学科奇才颜庆应教授 一手科研一手商 教课写作不耽误”.