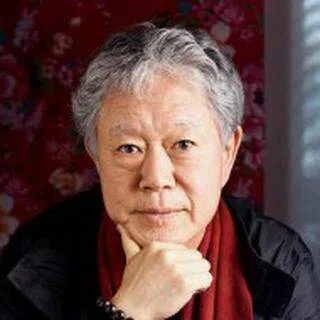

Taiwanese art historian: The joy of sharing food in old Taiwan

Taiwanese art historian Chiang Hsun reminisces about the good old days of simple food and heartfelt folk religious festivals, where regular households threw banquets and opened their doors to friends and strangers. It is in those vignettes of daily life that all of Taiwan's generosity, harmony, magnanimity and acceptance are on display.

As far as I can recall, I rarely ate at restaurants before I turned 25.

This is probably true for other Taiwanese back then - going to restaurants meant entertaining clients or celebrating a wedding or someone's 80th birthday. People ate at home on normal days.

The three square meals they had at home were very simple as well. If the household was small, there would be two vegetable dishes and a soup; if it was a larger family, there would be four vegetable dishes and a soup. People mainly ate vegetables with a bowl of rice or noodles.

When I was little, there was always tofu and vegetables in our meals. We also ate a lot of fish and small clams (蚬仔). The saying "摸蛤兼洗裤" (wash your pants while picking clams) actually refers to these clams. After school, I would rush off with my bamboo basket to gather clams at the freshwater stream nearby. I would later mash up the meat and feed them to the ducks. Later on, it was said that freshwater clams could cure liver disease so they became really expensive when a liver disease epidemic broke out. The stream became polluted and these creatures disappeared.

Eating vegetables is different from being a vegetarian and has nothing to do with religion. We often ate a variety of vegetables, at least five grains and some bean products along with shredded or diced meat, fish, and shellfish.

It's just that ordinary life should be simple and plain as they ought to be, and the supporting cast should not upstage the star.

For example, when we cooked mapo tofu and yuxiang eggplant (鱼香茄子), we would first stir-fry some minced or diced meat to bring out the flavours and coat the pan with oil. But we had no doubt that the tofu and eggplant were the stars; the minced meat was just the supporting cast. Such dishes with more vegetables than meat in them shaped my concept of a "balanced" meal, and continue to influence my views on the body and life till today.

But don't get me wrong - we didn't abstain from meat or delicacies. It's just that ordinary life should be simple and plain as they ought to be, and the supporting cast should not upstage the star. Cutting off a bear's paw, pulling out a cow's tongue, slicing off a gorilla's lips - this all sounds rather chilling. When delicacies are served, I would often remind myself to just take a small bite, in case I can't stop. After all, after sampling the exotic, we return to our ordinary lives at the end of the day. If we taste wonderful dishes every day, wonder loses its significance.

In the days when Mother helmed the kitchen, Taiwan was still an agricultural economy and ordinary people lived simple lives. I was never able to relate to Tang dynasty poet Du Fu who said that the wealthy had so much wine and meat that they started to rot and smelled foul (朱门酒肉臭).

When I was little, I lived at Dalongdong, a little enclave of the Tong'an (同安) people. The residents there were mostly merchants who ran small businesses and were quite well-off. But they weren't the filthy rich who had so much wine and meat that they started to rot. Taiwan is not cold either, so the streets weren't littered with the bones of the poor who froze to death (路有冻死骨). We were very lucky to have lived an ordinary life, so we did not have a strong sense of class consciousness.

When our neighbours' baby turned a month old, they sent us some Chinese sticky rice. When Mother made baozis (包子, steamed buns with various fillings), she shared them with our neighbours too.

Everyone lived ordinary lives and there wasn't much envy or jealousy.

Worshipping the gods

We only ate more extravagantly during the festivities, which were mostly related to temple worship.

Dalongdong is full of temples. Right in front of our house sat the Dalongdong Bao'an Temple. The Confucius Temple was situated nearby. A little further away, about a five-minute walk to the northwest, was the Jiao Hsiou Temple (觉修宫), while the Pingguang Temple (平光寺) and Lin Chi Temple (临济寺) were situated to the east. Another ten-minute walk away, located near to Dadaocheng (大稻埕), were even more temples such as Ling-An Association (灵安社) and the Xiahai City God Temple (霞海城隍庙).

... where there is worship, there are food and drinks.

Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist temples were all around. Where there are temples, there is worship. And where there is worship, there are food and drinks.

The Confucius Temple holds a commemoration ceremony on 28 September every year, which sees the attendance of government officials. The ritual includes a Ba Yi Dance (八佾舞, eight-row dance), performed by my alma mater Dalong Elementary School. I took part in the performance once - I shaved my head, wore a long robe, held a pheasant feather and swayed from side to side. It wasn't exactly a pleasing sight - we went on an empty stomach and had to hold our hunger in until the government officials arrived. By the time the music played and fireworks were set off, the weaker among us already started vomiting or fainting.

All of Taiwan's generosity, harmony, magnanimity and acceptance are found in its common folk.

The type of worship sessions I loved most were the events organised by ordinary folks. These were neither fully Confucian, Buddhist or Taoist festivals but simply folk religion rituals involving food and drink. On these occasions, regular households - not wealthy families - held buffet banquets for everyone to join in.

I loved attending these banquets with my friends up until the time I left for university. We ate our way from Dalongdong to Dadaocheng, and from Wanhua's Bangka Lungshan Temple (艋舺龙山寺) to Qingshui Temple. All of Taiwan's generosity, harmony, magnanimity and acceptance are found in its common folk.

Taipei had changed by the time I returned from Europe and started teaching at a university. But I still enjoyed bringing my students to Tainan to participate in the King Boat ritual (王船祭). While we were there for a "field trip", how could we miss out on having a hearty meal? That was the 1980s. McDonald's had opened in Taiwan but the students were still amazed by the large banquets in the countryside.

Folk rituals dearly missed

Traditional folk worship is vibrant, noisy and lively. The food served at these "banquets" are also some of the most high-quality and value for money I've ever seen. Outside the temples, during the Seventh Month Pigs of God Festival (猪公), even the sacrificial pigs with their mouths stuffed with pineapple slices seem to be smiling from ear to ear. There's no room for petty feelings, tears, sadness or grief.

Nowadays, you don't see many folk rituals taking place. Apparently because they go against good morals or social ethics (有违善良风俗), they've been explicitly prohibited.

As soon as the government intervenes, "good" morals or social ethics immediately turn "bad". Everyone sees just how "bad" social customs are whenever the elections draw near.

It was like watching the eight immortals cross the sea, as each troupe had their own special talents.

I miss folk rituals. Taiwanese opera performances used to be held for a few months a year outside the Bao'an Temple. The best opera troupes across the island would take turns to perform. When it was time to commemorate the birthday of Baosheng Dadi (保生大帝, Grand Emperor of Life Protection), there would be three stages set up in front of the temple. Three plays would be enacted at the same time over a couple of days. As the three plays had the same content, each troupe had to be creative about giving a unique performance. It was like watching the eight immortals cross the sea, as each troupe had their own special talents.

The audience responded with thunderous applause and businessmen generously gave cash rewards, throwing banknotes on a large red sash. The whole process was direct and in full view of the public. Even the congratulatory message was a simple "good show", and nothing convoluted or coy.

I used to always look forward to this time of the year. After watching the performance, we would visit people's homes and feast at their banquets.

Dining with our backs to the coffins

Once, a friend of a friend invited us to a coffin shop to partake in their banquet. There was no address but we eventually found a shop with two rows of coffins stacked against the walls, and six or seven tables placed in the middle. "This is it," everyone said. The owner greeted us warmly, saying, "Oh, you must be Ah Quan's friends. Have a seat!" We started eating as soon as we sat down with our backs against the coffins. Soon after, "Ah Quan" joined us but it was not the Ah Quan my friend knew. Our friend apologised profusely and quickly got up, embarrassed. But the owner insisted that we stayed. "You guys are one of us," he said.

A while later, we found another coffin shop with a similar layout. It also had two rows of coffins placed upright against the walls, leaving a space for the living to sit. This time, we only started tucking in after confirming that the owner was indeed the "Ah Quan" our friend knew.

Blessings flowed from the heavens, the earth and the gods. This is the Taiwanese folklore that I witnessed as a teenager.

Good shows should go on along with a free flow of good food. We were able to enjoy good shows and good food only because we were celebrating a deity's birthday and sharing in its divine blessings. Blessings flowed from the heavens, the earth and the gods. This is the Taiwanese folklore that I witnessed as a teenager.

There are not many coffin shops nowadays. I guess all the "Ah Quans" have grown old. Nobody talks about these good customs anymore either.

Such banquets do not take place every day. Once the rituals end, opera troupes would pack their props and costumes into a small truck, and the women who played the role of young ladies in the opera (小旦) would breastfeed their babies next to the trucks, unbuttoning their tops with one hand and directing the loading and packing with the other. They were calm and composed, much like Mu Guiying, a legendary heroine and cultural symbol of a steadfast woman.

I first encountered "sadness" when I saw what happened after the end of an opera performance. The helmets, armour, swords, spears, cymbals and drums were all packed up, and the babies were crying after drinking milk. The opera actress put down her child, stood before the gods, and clasped her hands in prayer, pious and sincere. The truck's engine started, and it soon scooted off, kicking up clouds of dust. Looking at the truck drive further and further away, I knew that the festivities were over, and understood what "sadness" was.

After the noisy festivities were over, we humbly returned to eat Mother's ordinary home-cooked meals.

This not only applied to my family - back in those days, mothers were often the ones who took care of the family's three meals. At the 44 Kan site, a commercial street, it was the women who busied themselves with preparing three meals a day. Buying groceries, washing them, cooking rice, preparing dishes... The women worked all day in the kitchen.

Dinner at dusk was at a big round table in the dining room. The men ate at the table first, drinking alcohol and also scolding people. After they were done, the women ate the leftovers with the children. Then, the women cleared the table and squatted on the floor by a large basin to wash the dishes and chopsticks. Finally, they put a kettle on the stove for hot water to wash the feet of the men before they went to bed.

A doctor friend of mine told me that men from that era mostly suffered from oral cancers because they always ate piping-hot food. He said, "Eating after the food has cooled a little is better." This was his finding, which I didn't verify.

Mother's dishes

Mother cooked three meals a day for our family of eight so she often had to think of new ideas for her dishes. Using flour, she made baozis, mantous (馒头, steamed buns) and dumplings. She made thick and thin noodles by hand, which were incredibly springy, unlike those made by machines.

Mother also made mao erduo (猫耳朵, lit. "cat's ear", gnocchi-like dumplings), which was called ma shi (麻什) back in her hometown. It should be a staple of the northwestern region, but I'm not quite sure of the exact term.

One makes ma shi with an action that has a "ci" sound. I'm not sure of the Chinese character but that was how Mother pronounced it. "Ci" means using your thumb to roll small pieces of dough into the shape of a cat's ear. These concave gnocchi-like dumplings are boiled in water until they are 80% cooked, then placed in boiling stock to absorb their flavours. This dish is more flavourful than noodles.

It was very much like a family craft assembly line - one person cannot get the job done, everyone must help out.

Mao erduo is entirely handmade. Mother was often the one who kneaded the dough, rolled it up, cut it into strips and separated them into small dough pieces. My siblings and I would then roll them into the shape of a cat's ear. When Mother made dumplings, she was also the one in charge of making dumpling wrappers and preparing the filling. Then we would all wrap them together. It was very much like a family craft assembly line - one person cannot get the job done, everyone must help out.

Eating at home, cooking together, and sharing laughter and banter is also a type of parent-child relationship.

Mao erduo stock is made with tomatoes, enoki mushrooms, shredded egg crepe, shredded carrots, peas, shiitake mushrooms, black fungus, and shredded (or diced) cabbage. None of the ingredients are expensive, but the broth of such ingredients would be bursting with flavour. Back in those days, Mother called the stock shao zi (哨子).

I guess because Mother fled from place to place during the war, she learned how to make various local dishes along the way. For instance, she knew how to make many types of noodle dishes. Among them was qihua mian (旗花面), made by cutting dough sheets into small rhombuses. I loved watching Mother slice the stack of dough sheets with her big cleaver. She would slice the layers of dough sheets diagonally and then lengthwise. When the pieces fell into place, they would become neat and uniform rhombuses the size of a fingertip, and resemble carved flowers or paper-cut art (剪纸). Paper cutting is an art form now. Back in those days, housewives would skilfully make delicate paper cuttings with a simple pair of scissors. Slicing dough and cutting paper utilise the same skill set.

During the Chinese New Year festivities, beautiful paper cuttings with designs more exquisite than Louis Vuitton's would be stuck on the windows of every household.

Later, I saw an elderly woman work her magic on a thick stack of papers and a pair of scissors in a yaodong (窑洞, an earth shelter dwelling) in northern Shaanxi. During the Chinese New Year festivities, beautiful paper cuttings with designs more exquisite than Louis Vuitton's would be stuck on the windows of every household. In such artwork, there was no "artist" - every woman could count herself as a professional artisan of paper cuttings, making such art from a young age until she married and became a mother. In the same way, women used their paper cutting skills to whip up noodle dishes for their families. Mother inherited this muscle memory; her hands remembered the way handicrafts were made by ordinary women from thousands of years ago.

With her single pair of hands, she took care of our family's three meals, and didn't make us feel like we missed out on dining out at restaurants. On the contrary, I am lucky that I enjoyed home-cooked meals every day until I was 25. Not to mention that I had lunch boxes to bring to school with me. Each time I opened them, my classmates even wanted to exchange their lunch for mine.

We never had a luxurious kitchen or exquisite, state-of-the-art kitchenware. Our pots, pans and dishes were all simple and plain: big earthen jars, big iron pots and iron ladles, bamboo chopsticks, stone chopping boards, wooden rolling pins of different lengths... But the most ordinary elements of Metal, Wood, Water, Fire and Earth created the most extraordinary flavours I've ever tasted in my life. Sweet, sour, salty, spicy and bitter tastes; I learnt how to appreciate each and every one of them. They are the flavours of the dishes that Mother prepared by hand, and also the flavours of life that Mother patiently let me experience.

Learning to count our blessings

Sometimes I wonder which of Mother's dishes I miss the most. Our kitchen was so plain and most ingredients were inexpensive. Mother rarely cooked with luxury ingredients.

Now that I think about it, Mother never cooked with expensive ingredients like shark's fin, abalone or lobster.

Father always told us to put our hands behind our backs. Maybe he believed that killing a chicken was bad karma, so he made us do that to show that the children were not involved and so no harm would come to us.

We kept many chickens, ducks and geese, but only for their eggs, so we had eggs to eat every day. Unless we were celebrating a festival, there wouldn't be meat on the table. When I say "meat", I am referring to whole chickens, whole ducks and big slabs of pork. Pork knuckles, chickens and ducks were delicacies reserved for Chinese New Year's Eve.

A few days before Chinese New Year's Eve, I would be woken from sleep by the yelps of pigs being slaughtered. It was a little terrifying, but also quite exciting. We slaughtered our chickens and ducks ourselves - Father was in charge of this. He would first pluck the feathers around the throat of the bird, and boil some water to scald the chicken or duck before plucking the rest of the feathers. We would gather around him to watch. Father always told us to put our hands behind our backs. Maybe he believed that killing a chicken was bad karma, so he made us do that to show that the children were not involved and so no harm would come to us.

We were especially happy during such festivities because we got to eat dishes we didn't normally eat, and the atmosphere was celebratory. Whole chickens, ducks and fish would be on the table, and we first worshipped our ancestors, thanked the heavens and the earth, before finally digging in - it was all a blessing that we would never forget.

I always feel that we would be "trampling" on our blessings if they got all too many and we all got too greedy. We "trample" on our blessings when we don't cherish good things. So, even today, I am still excited and joyous when I occasionally eat steak, Buddha Jumps Over the Wall, shark's fin and lobster. But I've never tasted bear's paw and gorilla lips. Every time I see the luscious lips of gorillas at the zoo, I do think about what those flexible lips would taste like. They are the real "famous mouths" (名嘴, referring to famous pundits).

Whenever I see a pot of Buddha Jumps Over the Wall, I still exclaim, "Wow, so many chicken testicles!" But, eating a pot full of "testicles" for three consecutive days is definitely a bad idea. When it comes to testicles, two are enough. Eat too much and it becomes disgusting. Not only would your stomach hurt, you would feel sorry for having good things and feel guilty about "trampling on" your blessings.

This is what Father and Mother taught me. Or rather, the education I received from that era. It may not be the greatest piece of truth, but it taught me to count my blessings and cherish them, instead of trampling on them under my feet.

The next generation grew wealthy and stuffed their faces with alcohol and food. Now they drive their father's Lamborghini and speed on the roads, knocking down people and fleeing the scene after. It almost seems like a trend nowadays - what can we do?

Each generation has their own habits. I can't change mine, and the next generation won't change theirs. May we each cherish our blessings and pray that they will not be trampled on to the point of extinction. May our island always be blessed.

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as "母親的家常菜(上)".

Related: Life and life lessons in the old markets of Taiwan | Taiwanese art historian: The five elements of cooking in the olden days | Taiwanese art historian: Why a mother's winter melon soup is best | The old days of eating well without a refrigerator | Pickled vegetables, fermented beancurd and stinky egg: An art historian's love of preserved foods | Remembering Mother's cleaver in the 'Palace of Versailles kitchen'