How Qi Faren helped launch China into space — and why it still matters

Qi Faren, chief designer of China’s Shenzhou 5, shared his lifelong dedication to China’s aerospace journey — from early missile development to manned spaceflight — with Lee Huay Leng, editor-in-chief of SPH’s Chinese Media Group, in 2004. In the interview collected in Lee’s new book,《思索的长度》(A Long Thought), Qi reflected on patriotism, self-reliance and the spirit that has driven China’s space program through adversity — values that continue to underpin the country’s pursuit of technological advancement today.

While many Chinese were excited at the successful launch of the Shenzhou 5, some privately criticised putting money into such “vanity” projects when a lot of rural folk in China were struggling to put food on the table.

Qi Faren would probably disagree. Not because the project earned him the accolade of “chief designer of the Shenzhou 5 manned spacecraft”, but because he came from that generation of Chinese people, and was involved in developing China’s first copied missile (Dongfeng-1); he was the technical director of the launch of China’s first nuclear missile and the first satellite (Dongfanghong-1); he sent satellites into space until he became the chief designer of the Shenzhou series of spacecraft at the age of 59.

All of this gave him a deeper sense of the great historical context behind China’s space technology, from when China “stood up”, through the chaos, poverty and backwardness of the Cultural Revolution, to the incredible changes since reform and opening up.

For him, going from the “two missiles” to satellite launches and then to manned spacecraft was not purely for vanity’s sake. It was “what the country and the people needed”, and also what China needed strategically on the international stage.

“The Soviet Union wouldn’t supply us, nor would the US. So we did it on our own. That is why our aerospace creed mentions self-reliance: you must have your own intellectual property, things of your own...” — Qi Faren, Chief Designer, Shenzhou 5

China aerospace’s self-reliance

Qi was born in 1933 in Fuxian county, Liaoning, and grew up in Dalian. When northeast China came under Japanese occupation, he became a subject of the Japanese emperor, and it was not until 1945, when the Soviet Union liberated northeast China, that Qi realised he was Chinese.

After that, his memories were of American bombings and strafings during the Korean War, and a sense of injustice at the country being weak and getting bullied, so that when he took the university exams, all he wanted was to dedicate himself to his country and go into national defence.

In 1961, the Soviet Union withdrew all its experts assisting China — even in 2004, China was still facing US embargoes. These unpleasant experiences inspired Qi’s generation of Chinese scientists to work hard, and gave them a deeper sense that to gain global respect, China had to make advances in these cutting-edge technologies.

“Every time I went to the US, there were embargoes. People would be willing to sell to you and talks would go well, but after that, they wouldn’t sell. In the early 1980s, when we had just opened up, a group from the European Space Agency came. When they found out that our satellites were entirely made in China without a single foreign component, they said we were amazing, but also foolish. Because science is universal, why didn’t we use foreign components? But we said: you won’t give them to us.

“Before the 1980s, we were in a tough international situation. The Soviet Union wouldn’t supply us, nor would the US. So we did it on our own. That is why our aerospace creed mentions self-reliance: you must have your own intellectual property, things of your own. Advanced technology cannot be bought with just money. People will sell to you if you have money, but if you have no money, no way.”

In the 1960s, China was impoverished, yet it still managed to develop missiles and atomic bombs. “Back then, without the ‘two bombs’, who would take China seriously? Foreign Minister Chen Yi himself said that without the ‘two bombs’, he wouldn’t be able to do anything.”

Qi says that it is the patriotism, dedication and unity of China’s researchers that have propelled the country’s space programme forward. And China will need this spirit in the future.

Qi felt that, in terms of practical application, everything from the research of the 1960s to today’s manned spaceflights represented real, tangible results.

“The Dongfanghong-1 satellite was a science experimental satellite used to measure physical parameters, such as space temperature, atmospheric density and so on, which China had never measured before.”

However, amid the Cold War and the Cultural Revolution, the political propaganda purpose of Dongfanghong overshadowed its scientific value. “Initially, it could’ve done without audio, but since the satellites for both the US and the Soviet Union had audio, ours played the song The East Is Red (《东方红》).”

Without these initial experiments, there would not have been the subsequent development or launch of application satellites — these satellites changed people’s lives without them even realising it.

“Previously, television worked on microwave transmission, and the quality was very poor. People saw blurry images, and there was a pile of unsold TVs. After the satellite launch in 1984, TV signal coverage increased from 30% to 80% of the population, and people could watch TV in colour. Nowadays, you can watch anything, including the Olympics. There are also meteorological satellites, and so on. Now we have more than ten satellites working in space, all closely tied to daily life. If satellites hadn’t been launched back then, our lives would be quite difficult.”

Going to space for the nation

Taking a historical perspective, manned space projects are also one step in preparation for the future. While it is currently only in the stage of scientific research, with no commercial benefits, Qi said: “In the long run, people will eventually have to go to space for work.” What is important is that in developing its space industry, China does not just follow others, but sees that “what suits oneself is best”.

“I believe that a country without a spiritual backbone cannot stand.” — Qi

In 1955, after obtaining a doctorate in aeronautics and mathematics from the California Institute of Technology in the US and working in applied mechanics and rocket and missile research, aerospace engineer Qian Xuesen chose to give up a cushy life and return to China. He once taught a course on missile fundamentals to Qi, who was in his early twenties. Qi wondered: “Why is such a great scientist giving lessons to us youngsters?”

Qi later figured it out on his own. “It was his commitment to his job. He did it for this people, this nation.”

He still remembers Qian saying that this career did not just require one or two scientists but a whole team. That spirit deeply influenced Qi throughout his life. Now, Qi says that it is the patriotism, dedication and unity of China’s researchers that have propelled the country’s space programme forward. And China will need this spirit in the future.

“Now, people are more open-minded and their values have changed, but we still need to foster a national spirit — something that endures in both good times and bad. This is a kind of mental strength. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, we did well in this regard, but the impact of economic transition has been significant. We need to promote it even more. I believe that a country without a spiritual backbone cannot stand.”

Qi is not talking about some vague, abstract idea driven by pure nostalgia or romanticism. He recognised that without a strong national defence and air force, China would be pushed around. This was why, when applying to university, all three of his choices were aerospace engineering courses.

Surviving the Cultural Revolution

Even during the Cultural Revolution — when many intellectuals were attacked and even disillusioned — he still felt the call of that same mental strength.

“The satellite launch happened to be during the Cultural Revolution. At the time, right and wrong were turned upside down, knowledge was not respected, and intellectuals were criticised. But driven by the interests of the country and the people, we kept working hard even though we were criticised and disrespected. Even if we were being sent to the cadre school [干校, rural communes established during the Cultural Revolution to train cadres to follow the mass line, including through the use of manual labour] the next morning, we would still work overtime to finish our experiments that night.”

In 1969 as China’s national day approached, the Red Guards came to his house to remove “class enemies” and ensure there were no “bad people”. His wife had already been sent to the cadre school, so he brought his elderly mother to Beijing to take care of his children. But once the Red Guards learned that Qi came from a landlord family, which meant that his mother was a “landlady”, they took her away. Although she was eventually released, it was no longer possible to stay in Beijing. Qi had no choice but to send his children back to the countryside with their grandmother.

Despite the grievances, Qi remained fully dedicated to the development of China’s first satellite, Dongfanghong-1. In 1970, when the satellite successfully broadcast the song The East is Red from space, he could not contain his emotions. Rushing to the stage at the celebration, what did this 37-year-old aerospace scientist say?

“We’ve finally succeeded! Our hard work paid off and we’ve lived up to the times and to our country.”

“The research environment in China in 1992 was tough, and the pay was low — people even said you’d be better off selling tea eggs than developing missiles.” — Qi

From crisis to flawless

Qi was 59 years old when China initiated its manned space programme in 1992. At that age, switching from satellite design to spacecraft design was incredibly difficult. Furthermore, “the research environment in China in 1992 was tough, and the pay was low — people even said you’d be better off selling tea eggs than developing missiles”. The space team faced talent drain as many left for foreign or private enterprises. Yet driven by the same spirit, Qi took on the task. He said, “We old timers led a group of youngsters and worked on it for over a decade.”

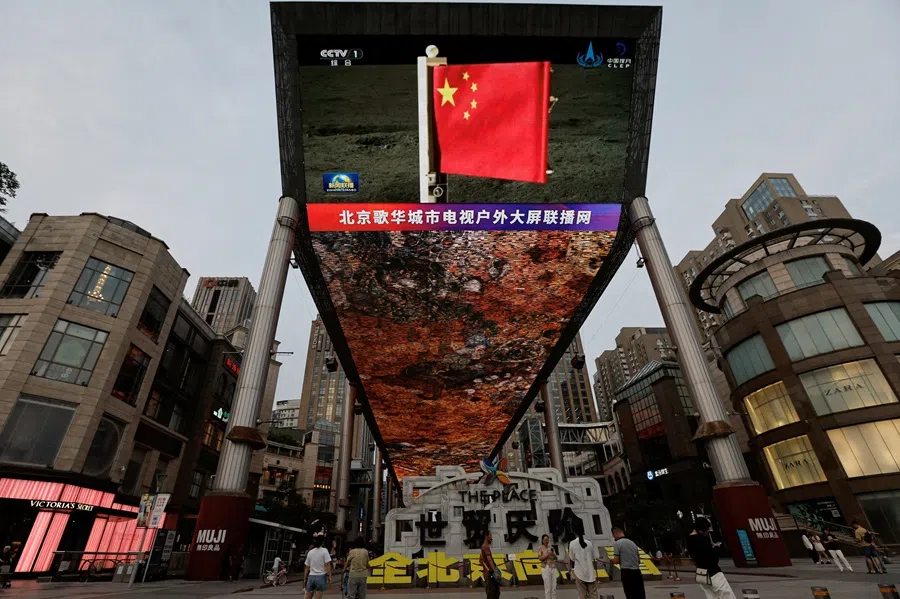

As a result, the Shenzhou series — from unmanned spacecraft to the nearly flawless 2003 Shenzhou 5 manned mission — finally propelled China into the ranks of countries with manned spaceflight capabilities.

Qi dedicated his entire life to China’s aerospace cause. Even when his wife was diagnosed with late-stage lung cancer, he remained busy working on the Shenzhou 2 spacecraft and could only visit her at night. After entering the base, he would be away from home for months at a time, and could only comfort his wife via daily phone calls. His wife passed away in 2001.

As for today’s younger generation, he does not expect them to work as tirelessly and selflessly as his own generation did, because that era is over. “For us, we never chose what we wanted to do — the director chose for us. Now, if someone is unhappy, they can say, ‘I quit.’ This is a new thinking and a new trend. I would also consider it progress.”

“The other key is a sense of collective belonging. Many things can’t be bought with money, nor solved by salary alone.” — Qi

But Qi hopes that China’s space industry can retain talent — people who not only possess knowledge, but also embody the aerospace spirit of “self-reliance, hard work, selfless dedication, strong coordination, pragmatism, and the courage to climb”.

He said, “Today’s young people are just as knowledgeable and capable as we were, but there’s still a gap when it comes to the spirit of dedication. To retain people, first and foremost, we need a meaningful mission — something they genuinely want to work on. Of course, compensation shouldn’t be too low, but if the mission is compelling enough, they’re willing to accept ‘less’, not ‘nothing’. The other key is a sense of collective belonging. Many things can’t be bought with money, nor solved by salary alone.”

The book is available for purchase online at bookshop.sg, ZShop, Amazon and Sea Breeze Books, as well as major bookstores including Kinokuniya, Maha Yu Yi Pte Ltd, POPULAR Book Company, Union Book Co Pte Ltd and City Book Room.