Huawei vs Cambricon: Can two Chinese ‘Nvidias’ stall China’s AI ambitions?

The contest between Huawei and Cambricon is less about which company will be crowned “China’s Nvidia” and more about whether China can avoid becoming its own biggest competitor. Technology industry professional Akhmad Hanan explains why.

China’s ambition to achieve technological self-reliance has found its most intense battleground in artificial intelligence (AI) semiconductors. For Beijing, developing a homegrown counterpart to Nvidia, the undisputed leader in AI accelerators, has become both a strategic and political priority. Yet, the answer to who truly deserves the title of “China’s Nvidia” is far from simple.

Huawei’s breakthroughs

Two firms, Huawei and Cambricon Technologies, have emerged as frontrunners. Their rivalry not only underscores Beijing’s industrial policy dilemmas but also reveals how fragmented innovation can complicate China’s push for global tech leadership.

For Beijing, Huawei’s scale and integration make it the safest bet to underpin national AI capacity, especially in training large language models and powering government data centres.

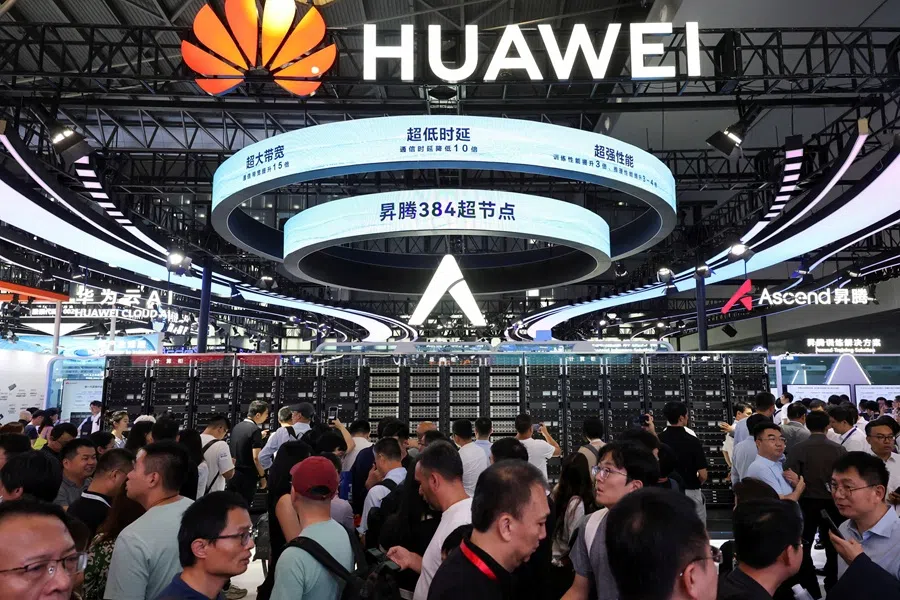

Huawei, long established as a global telecom and ICT giant, entered the AI chip race through its HiSilicon design arm with the launch of the Ascend series. Chips such as the Ascend 910 and its successors, the 910B and 910D, have been pitched as direct alternatives to Nvidia’s A100 and H100.

Combined with Huawei’s Atlas supercomputing clusters and its in-house MindSpore AI framework, the Ascend line is embedded in a vertically integrated ecosystem spanning chips, servers, cloud services and enterprise solutions.

For Beijing, Huawei’s scale and integration make it the safest bet to underpin national AI capacity, especially in training large language models and powering government data centres.

Faster and smarter AI

At Huawei Connect 2025 in Shanghai, the company revealed its long-term roadmap for AI chips for the first time. The plan includes the release of the Ascend 950 series in 2026, featuring two variants: the 950PR, optimised for prefill inference to speed up predictions and recommendations; and the 950DT, capable of decoding inference — interpreting data — and model training.

Huawei is also developing its own high-bandwidth memory, dubbed HiBL 1.0, to reduce reliance on suppliers such as SK Hynix and Samsung. The Ascend 950PR will feature approximately 128 GB of memory with a bandwidth of 1.6 TB/s, enabling it to process large amounts of data quickly. Meanwhile, the 950DT will offer even more capacity, with 144 GB of memory to handle larger and more complex tasks. These chips will anchor the company’s Atlas 950 and 960 SuperClusters, designed to connect hundreds of thousands of Ascend processors for both inference and training.

Still, Huawei’s ambitions are constrained by sanctions. US officials estimated earlier this year that the company may not be able to produce more than 200,000 advanced AI chips annually under current restrictions. To bridge the gap, Huawei has prepared the Ascend 910C, a transitional product ready for mass shipment to Chinese clients as access to Nvidia’s hardware tightens.

Benchmarks suggest [Cambricon’s] Siyuan 590’s performance already reaches about 80% of that of Nvidia’s A100, while the Siyuan 690 aspires to rival the H100.

Cambricon’s rapid rise

Cambricon offers a different model. Spun out of the Chinese Academy of Sciences — China’s premier national scientific research institution — in 2016, it has positioned itself as a pure-play AI chip designer. Its Siyuan series, particularly the Siyuan 590 and upcoming Siyuan 690, demonstrates rapid progress.

Benchmarks suggest the Siyuan 590’s performance already reaches about 80% of that of Nvidia’s A100, while the Siyuan 690 aspires to rival the H100. Unlike Huawei, Cambricon lacks its own captive cloud or telecom ecosystem. Instead, it supplies chips to other Chinese giants, including Baidu, Alibaba and iFlytek.

What has propelled Cambricon into the spotlight in 2025 is its financial turnaround. After seven consecutive years of losses, the company posted a net profit of 1.03 billion RMB (US$145 million) in the first half of the year, compared with a 533 million RMB loss during the same period in 2024. Revenues surged to 2.9 billion RMB, an eye-popping 44-fold increase.

Investors responded with enthusiasm: Cambricon’s market capitalisation more than doubled within a month, peaking around 580 billion RMB. Its stock jumped 130% in August alone before correcting sharply with a 14% single-day drop. The company has since raised 4 billion RMB through additional share issuance to bolster R&D. Still, its domestic market share remains modest, about 3%, but demand from ByteDance, Tencent and others is beginning to shift some inference workloads away from Nvidia.

Cambricon’s Siyuan 690 is aimed squarely at the same high-end market Huawei is targeting with the Ascend 910D.

Fragmentation risks

These contrasting models highlight how the two companies divide the AI landscape. Huawei dominates training, where massive clusters are required to build large models. Cambricon has found more traction in inference, powering enterprise and edge applications.

In theory, this division of labour could be complementary. In practice, however, the boundaries are increasingly blurred. Cambricon’s Siyuan 690 is aimed squarely at the same high-end market Huawei is targeting with the Ascend 910D.

For Beijing, this presents a policy dilemma. Supporting multiple champions can foster competition and accelerate innovation, but fragmentation risks diluting resources and weakening China’s international competitiveness.

Without convergence, China risks building parallel, incompatible ecosystems, neither large enough to seriously challenge Nvidia.

Unlike Nvidia, whose global dominance rests not only on hardware but also on its CUDA software ecosystem — which helps developers build and run high-performance applications optimised for Nvidia’s hardware —Chinese firms are still scrambling to win developer loyalty.

Huawei promotes MindSpore, its own AI development platform. Meanwhile, Cambricon is refining its inference toolchain — software tools that help AI models make faster and more accurate predictions. Without convergence, China risks building parallel, incompatible ecosystems, neither large enough to seriously challenge Nvidia.

Future choice: Governments and Institutions

The broader geoeconomic stakes are clear. With US export controls tightening access to Nvidia’s cutting-edge chips, Chinese firms are forced to rely on domestic alternatives. This bifurcation is creating two technological spheres: one centred on Nvidia and its global ecosystem, the other on Huawei, Cambricon and other Chinese players.

Southeast Asia and parts of the Global South may eventually face pressure to choose between them, much as they did during the 5G rollout. In this context, Cambricon’s lower-cost inference chips could gain traction among enterprises, while Huawei’s integrated superclusters may appeal to governments and research institutions.

Neither Huawei nor Cambricon has yet matched Nvidia’s maturity in software, developer tools or access to advanced fabrication processes.

Yet, the long-term sustainability of China’s AI chip strategy remains uncertain. Neither Huawei nor Cambricon has yet matched Nvidia’s maturity in software, developer tools or access to advanced fabrication processes. The world’s most sophisticated chips are still manufactured by TSMC at cutting-edge nodes, largely off-limits to Chinese firms under US export restrictions.

Even if Chinese chips close the performance gap, efficiency, energy consumption and software compatibility remain hurdles. Meanwhile, Nvidia continues to expand its dominance, holding more than 80% of the AI data centre market, protected by a software moat competitors struggle to breach.

Two Chinese ‘Nvidias’

Paradoxically, China may not end up with one “Nvidia” but two: Huawei, the vertically integrated giant backed by the state, and Cambricon, the nimble specialist vying to be “China’s little Nvidia”.

This dual-track approach could invigorate domestic innovation in the short run, giving Chinese firms more options and creating pressure to improve. Yet what looks like strength may also sow weakness. Rival champions mean rival ecosystems, different software stacks, toolchains and industry alliances that risk splintering the very market Beijing is trying to consolidate.

The real test for China’s semiconductor strategy is not whether it can produce chips that match Nvidia’s raw power, but whether it can build a coherent ecosystem that attracts developers, investors and global partners. Without unity, Beijing’s drive may deliver technically impressive products and temporarily buoyant firms but fail to shift the balance of global AI power.

In the end, the contest between Huawei and Cambricon is less about which company will be crowned “China’s Nvidia” and more about whether China can avoid becoming its own biggest competitor.