Innovative drugs: The new battleground in US-China rivalry

The race for innovative drugs has become a defining front in US-China competition. While the US leads in original innovation, China is rapidly advancing through strategy, scale and efficiency, shaping the future of global pharmaceutical development, says NUS Emeritus Professor Ong Choon Nam.

Biotechnology is increasingly becoming a focal point of geopolitical competition between major powers. China launched its “Healthy China” strategy in 2015, aiming to establish innovative drugs as a key area of independent innovation by 2030. The US, in turn, views this as a challenge to its technological dominance and even its national security.

What are innovative drugs?

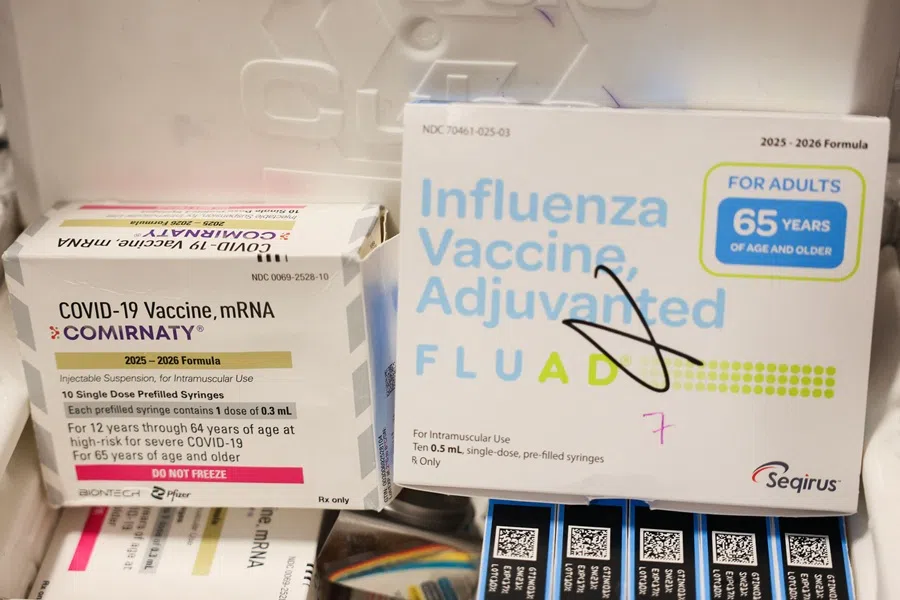

An innovative drug is a medication with intellectual property that features a significant breakthrough in its mechanism of action, chemical structure, or therapeutic efficacy. Compared to existing drugs, it offers clear advantages in efficacy, safety, or route of administration. The Covid-19 mRNA vaccine is a prime example of an innovative drug. Simply put, an innovative drug is an original, brand-name product manufactured using biotechnology, rather than a generic “copycat”.

Innovative drug development is a long, costly and high-risk undertaking. The R&D cycle is long, often taking more than 10 years from initial discovery to market, and requires substantial investment, typically amounting to hundreds of millions of US dollars. Furthermore, there is a high risk of failure, and many candidates never reach approval. To offset these massive investments and high attrition rates, successful innovative drugs receive patent protection, which allows for high initial pricing upon market entry.

Due to these characteristics, innovative drugs meet substantial clinical needs, provide better treatment options for patients, and serve as a key indicator of a nation’s scientific and medical capabilities.

The competition between both powers in biomanufacturing has moved beyond market share, escalating into a full-scale contest over critical technologies, talent and global healthcare strategy.

A clash of national strengths

The capacity for innovative drug development has become a core measure of a nation’s scientific strength. The US has long maintained a dominant position, relying on deep fundamental research, a mature venture capital ecosystem, and the global credibility of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In contrast, driven by policy and capital over the last decade, China’s biomanufacturing industry has developed rapidly and is now challenging the US’s lead. The competition between both powers in biomanufacturing has moved beyond market share, escalating into a full-scale contest over critical technologies, talent and global healthcare strategy.

Some believe the next round of Sino-US rivalry will be centred on innovative drugs. The mutual learning and competition between the two countries in cutting-edge biotechnologies like oncology, immunology, gene, and cell therapy will profoundly shape the global pharmaceutical innovation landscape.

US: research, capital, regulation

The US advantage is rooted in its mature “research-capital-regulation” tripartite ecosystem.

One, fundamental research leadership and efficient translation: established in 1887, the National Institutes of Health is the world’s largest funder of bioscience research, providing billions annually to drive novel innovation. Concurrently, technology transfer offices at top universities and medical centres (such as Harvard, Stanford, MIT, and so on) effectively commercialise lab patents, spawning many biotech startups.

Two, venture capital and the talent magnet effect: specialised venture capital clusters in Silicon Valley and Boston provide both funding as well as R&D strategies and industry networks. Their high-risk tolerance aids in the development of disruptive technologies and continually attracts top global talent, forming an effective innovation network.

The FDA’s review standards are seen as the “quality gatekeeper” for drug standards. Approval grants a “passport” to the global market, providing the drug with high credibility and pricing power, which in turn attracts global capital investment.

Three, FDA regulation and credibility: the FDA’s review standards are seen as the “quality gatekeeper” for drug standards. Approval grants a “passport” to the global market, providing the drug with high credibility and pricing power, which in turn attracts global capital investment.

China: state ambition, market size, talent accumulation

China’s rise is driven by a combination of state will, a massive market and regulatory reform.

One, national strategy and policy incentives. Innovative drugs have been elevated to a national strategic level since 2015. The National Medical Products Administration reformed its review process, significantly accelerating new drug approvals. Adjustments to the national medical insurance catalogue have released payment capacity for innovative drugs, while accession to the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) has aligned its pharmaceutical regulations with global standards.

Two, clinical trial resources and speed. A 1.4 billion population provides a unique advantage for patient recruitment, allowing clinical trials to be completed faster. Collaborative development with local contract research organisations further reduces costs and increases efficiency. These enhancers allow rapid progression from early-stage “fast-following” to “high-quality” development.

The return of many overseas-trained professionals and a focus on areas like cell therapy (CAR-T), gene editing and nucleic acid drugs provide China with the potential for leapfrogging or achieving a breakthrough by taking a different route.

Three, end-to-end cost control. A recent collaboration model among enterprises, hospitals and R&D institutions has accelerated the clinical translation process, helping the biomanufacturing sector develop drugs at a lower cost.

Four, accumulation of R&D talent. According to the 2024 Nature Index, while China still lags behind the US in life sciences, it is quickly approaching European levels. The return of many overseas-trained professionals and a focus on areas like cell therapy (CAR-T), gene editing and nucleic acid drugs provide China with the potential for leapfrogging or achieving a breakthrough by taking a different route.

Challenges on both fronts

Yet high R&D costs in the US, along with drug-pricing disputes like those surrounding the Inflation Reduction Act, may dampen incentives for innovation. Furthermore, supply chain dependence on Chinese active pharmaceutical ingredients poses a challenge as well. The “patent cliff” — the sharp drop in revenue when patents expire and competitors enter — is pushing many companies to partner with Chinese firms. Pfizer’s and Eli Lilly’s deals alone have reached nearly US$90 billion this year, as they race to replenish their R&D pipelines.

In China, the industry faces “involution” — capital clusters around a few popular disease targets, leading to fierce competition and price wars. Internationally, Chinese pharmaceutical companies still lack the brand credibility and pricing power of FDA-approved drugs.

Innovation with Chinese characteristics

For China, fully replicating or surpassing the US in all aspects may not be the goal. A wiser path is differentiated competition: biology is inherently diverse, rich in metaphor and governed by the constant norm of survival of the fittest. R&D can take an alternative route, starting from the genetic differences between ethnicities.

Focusing on diseases prevalent in Asia — such as liver and stomach cancers, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, dengue vaccines, and thalassemia gene therapy — allows companies to convert local knowledge into global advantage.

The extraordinary discovery of the anti-malarial drug, artemisinin, by Nobel laureate Tu Youyou demonstrates that TCM is an invaluable knowledge base and resource for modern biomedical innovation. Its integration with cutting-edge technology should be encouraged.

Artemisinin is a modern drug, but its discovery is deeply rooted in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). The plant from which it is derived — sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua) — has been used in TCM for more than 2,000 years under the name qinghao (青蒿) to treat fevers, including those linked to malaria. In the 1970s, Chinese scientist Tu Youyou and her team isolated the compound artemisinin (originally called qinghaosu) and confirmed its anti-malarial properties. Their breakthrough came from examining ancient TCM texts, which revealed that using a low-temperature extraction method, similar to wringing the juice from the plant, preserved the active component.

Today, artemisinin and its derivatives serve as the foundation of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), the World Health Organisation’s most effective and recommended treatment for malaria worldwide.

The extraordinary discovery of the anti-malarial drug, artemisinin, by Nobel laureate Tu Youyou demonstrates that TCM is an invaluable knowledge base and resource for modern biomedical innovation. Its integration with cutting-edge technology should be encouraged.

Another approach is to focus on areas where expertise is already established — such as cell therapy, gene editing, and nucleic acid drugs — turning scale and efficiency advantages into tangible global competitiveness.

Two possible scenarios

The US-China competition in innovative drugs, rooted in geopolitics, is reshaping the global biotech landscape and heightening the risk of intense rivalry. Two scenarios are possible in the future:

Cooperation and competition (co-opetition)

The US and China are fundamentally complementary in the pharmaceutical sector — the US relies on China’s supply chain and manufacturing capabilities, while China relies on US fundamental research and access to international markets.

Economically, both countries are concerned about high drug costs and seek low-cost alternatives, sharing common interests in global public health challenges such as rare diseases and emerging infectious threats. In the short term, decoupling would be painful for both countries.

In a framework of competition and cooperation, the US provides innovation and sets standards, while China accelerates execution, expands markets and optimises costs.

In a framework of competition and cooperation, the US provides innovation and sets standards, while China accelerates execution, expands markets and optimises costs. This complementary model of “high standards + large market” will fuel a multipolar and efficient global pharmaceutical landscape.

Decoupling, or pursuing separate paths

If decoupling happens, it could drive up the cost of innovative drugs and dampen scientific enthusiasm. Higher tariffs to protect US pharmaceutical companies would also affect investment confidence. The FDA may raise requirements for Chinese clinical data, raising barriers for Chinese firms entering the US market. Mechanisms like the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US would also strengthen scrutiny over biotech investments to prevent technology leakage and the acquisition of sensitive data by “unfriendly nations”.

However, crises also hold opportunity — it might spur Chinese pharma to actively explore third-party markets like Europe, for instance, through collaborations with European companies in the field of antibody-drug conjugates. As a Chinese Idiom says Saiweng shima (塞翁失马), it might just be a blessing in disguise.

Singapore: a gateway for Chinese drugs going global?

As a critical node in the global eco-business system, Singapore can serve as an “accelerator” for Chinese innovative drugs seeking to go global.

One, it is a high-quality partner. Singapore boasts top-tier scientific talent, expertise in recognised clinical trial systems (such as the FDA and European Medicines Agency), and production facilities that meet international standards. Eight out of the world’s top ten pharmaceutical companies have established operations here, contributing about 2.5% to Singapore’s GDP.

Singapore’s population disease profile reflects that of Asia, making it an ideal location for developing Asia-specific innovative medicines.

Two, it helps boost international credibility. International collaboration with Singapore can significantly enhance the global credibility of data and act as a stepping stone into the Southeast Asian market of 600 million people.

Three, it is a microcosm of Asian diseases. Singapore’s population disease profile reflects that of Asia, making it an ideal location for developing Asia-specific innovative medicines. Singaporean patients would also be the first to enjoy the benefits of innovative drugs tailored for Asians.

Four, the country is a global financial and talent hub. Singapore offers abundant private equity and a stable business environment. Its universities consistently produce well-rounded talent skilled in international regulations, making the city-state an ideal hub for Chinese pharma to secure financing and establish global headquarters.

Not a zero-sum game

The innovative drug competition is a microcosm of the US-China tech rivalry. The US retains its lead in original innovation with a mature ecosystem, while China is rapidly advancing through strategy and efficiency. This competition is not a zero-sum game; healthy co-opetition is expected to accelerate new drug R&D, lower patient medication costs, and ultimately benefit the world.

Looking ahead, both the US and China need to solve internal challenges — the US must control costs and China must reduce involution and promote novel innovation. For Chinese pharmaceutical companies, fully surpassing the US is not a short-term goal. A more realistic path is to achieve differentiated breakthroughs in specific disease and technology domains. Only through a global-minded R&D strategy and high-quality international cooperation can China secure an indispensable position in the global landscape.