Trump vs Biden: Who makes a better choice for Southeast Asia

The US presidential election on 3 November 2020 will be the most consequential in a generation, both for the US and the rest of the world. The lack of policy-oriented debate in the campaign to date means that the future of US foreign policy and the country's approach to the Asia-Pacific is unusually speculative regardless of which candidate wins.

On 1 October, President Donald Trump and First Lady Melania Trump tested positive for Covid-19, throwing another wild card into the heated election campaign.

If Trump is re-elected for a second term he is likely to pursue many of the same policies, domestically and internationally. The Republican National Committee opted not to publish a 2020 party platform, instead deciding to persist with the 2016 party platform. A second term is also likely to be characterised by the same rancour and unpredictability that marked his first term in office.

Unless Biden wins an overwhelming majority of the states, the popular vote and the electoral college, Trump could legally challenge the result, leading to political uncertainty and possibly violent protests for several months.

Unless Biden wins an overwhelming majority of the states, the popular vote and the electoral college, Trump could legally challenge the result, leading to political uncertainty and possibly violent protests for several months. Such a scenario would likely be more destabilising than the aftermath of the 2000 contested presidential election. The spectacle of political chaos would further undermine America's international image and reinforce the narrative that the US is a great power in decline.

If Biden does take office in January 2021 his administration is likely to be less unpredictable and more consistent than his predecessor, with fewer high-level resignations and fewer posts left unfilled. However, Biden will face enormous challenges, including containing the Covid-19 pandemic (which has claimed more than 210,000 lives in America) and the country's worst economic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s which it has caused.

Whichever candidate wins, Southeast Asian countries will find themselves at the centre of intensifying Sino-US rivalry, especially over the South China Sea where tensions will remain high or worsen.

Under Biden, US foreign policy will not "snap back" to that of the Obama era, though his administration may place a greater emphasis on strengthening America's relations with allies and international organisations which have frayed under Trump. America's more hardline strategy towards China will remain largely unchanged under Biden. The atmospherics of Sino-US relations could improve slightly and the tactics used by Washington to pursue this rivalry may also change.

The future trajectory of US-China relations under either Trump or Biden will greatly influence Southeast Asia's security environment. Whichever candidate wins, Southeast Asian countries will find themselves at the centre of intensifying Sino-US rivalry, especially over the South China Sea where tensions will remain high or worsen. Regional states will be watching events in America over the next few months with more anxiety than hope.

The Trump administration's mixed record

The Trump administration's engagement with Southeast Asia over the past four years presents a mixed record.

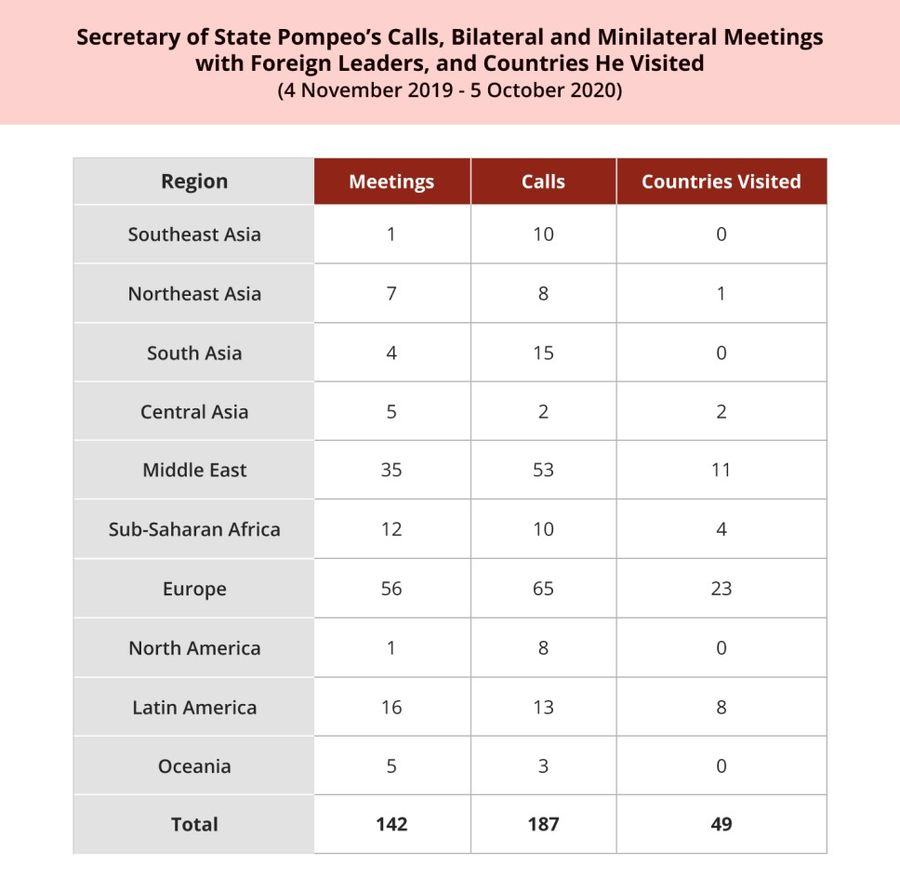

Trump has had very few bilateral meetings with Southeast Asian heads of government. In fact, over the last 11 months, Trump did not meet a single leader from Southeast Asia (see Table 1). Since March 2019, the only regional leader he met was Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in September 2019 in New York.

Although the White House no longer publishes a record of the President's phone calls with world leaders, it appears that Trump has rarely spoken on the telephone with Southeast Asian heads of government either. In April 2020, Trump did speak with Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte about the Covid-19 pandemic and ways to strengthen US-Philippine security ties.

Compared with the Obama administration, Trump has paid little attention to ASEAN.

Compared with the Obama administration, Trump has paid little attention to ASEAN. The President cut short his attendance at the East Asia Summit (EAS) in 2017, and in 2019 the administration sent America's lowest-level delegation ever to the EAS and ASEAN-US Summit. Due to the pandemic, the Special US-ASEAN Summit to be held in March 2020 in the US was postponed indefinitely. The 15th EAS scheduled for 11 November 2020 will likely be a virtual event. Trump's participation will depend on the political situation in the US a week after the election. Vice President Mike Pence may stand in for him, as he did in 2018.

According to State Department press releases, since the last EAS and ASEAN-US Summit in November 2019, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo's engagement with ASEAN has been limited. Pompeo participated in the Special ASEAN-US Foreign Ministers' Meeting on Covid-19 on 22 April (US time), the EAS Ministerial Meeting video call on 9 September, and the ASEAN-US Ministerial Meeting video call on the same day. He skipped the ASEAN Regional Forum Ministerial Meeting video call on 12 September and the first Mekong-US Partnership Ministerial Meeting on 11 September. Deputy Secretary of State Stephen E. Biegun led the US delegations for those regional meetings.

Between November 2019 and September 2020, outside of ASEAN-led mechanisms that include the US, Pompeo met with one senior Southeast Asian official (the Lao foreign minister on 28 June in Washington D.C.), called or participated in nine video or phone calls with regional foreign ministers, and one with Hun Sen, the prime minister of Cambodia (on 8 April) (see Table 2).

Economic engagement

Fortunately for Southeast Asian economies, they have not been a focus of the Trump administration's aggressive unilateralist economic policies. This, despite eight of the ten regional economies boasting trade surpluses with the US, with Vietnam's the largest and most unbalanced. Unlike with South Korea, and Canada and Mexico, the Trump administration has not sought to withdraw from the US-Singapore free trade agreement, America's only bilateral free trade agreement in Southeast Asia. Except for the Philippines, Southeast Asian states have not responded positively to the Trump administration's push for new bilateral trade deals. Two years after planned US-Philippine exploratory talks were announced, details on them remain sparse.

Southeast Asian economies have been affected much more by the knock-on effects of Trump administration trade and investment actions taken against other targets. Trump's early decision to withdraw the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was not determined by the participation of four Southeast Asian states in this mega-regional trade deal.

Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam persisted with the deal after the US withdrawal and signed the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in March 2018. More than two and half years later, though, Malaysia and Brunei have not ratified it.

The Trump administration's blocking of the appointment of new judges to the World Trade Organization's Appellate Body has seriously undercut the organisation's dispute settlement mechanism. However, Southeast Asian states are not particularly frequent complainants or respondents in WTO disputes. Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam have yet to file a complaint, while Malaysia and Singapore have filed one each in the past 25 years.

The Trump administration's more aggressive approach to China's economic policies long deemed unfair by the US, and China's responses to these Trump administration punitive actions, will have more effect on Southeast Asian economies. The 2020 ISEAS State of Southeast Asia survey report shows that 64% of those surveyed expect these knock-on effects to be bad for the region.

Defence engagement

America's defence engagement with Southeast Asian states has strengthened under Trump. Under its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) policy, the administration has promoted a networked region made up of bilateral alliances, partnerships and multilateral arrangements. The US government has also sought to increase arms sales to the region while trying to persuade regional states to end purchases of defence equipment from Russia and China.

Since Trump took office, US-Thai defence relations have been normalised, while security ties with Vietnam, Singapore and Indonesia have been further consolidated. Due to President Duterte's pro-China and anti-American leanings, the US-Philippine alliance has come under strain, though the country's national security establishment has been largely successful in preserving defence ties with America. Most significantly, in June 2020 the Duterte administration suspended for 6-12 months its February decision to terminate the 1998 Visiting Forces Agreement. Philippine-US relations during the Duterte administration improved when President Trump took over from President Obama. Military ties with Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos remained limited due to US sanctions.

The South China Sea dispute has been a major focus of the Trump administration's Southeast Asia policy. Since 2017, the US government has moved from merely criticising China's assertive policies in the South China Sea to labelling Beijing's claims and activities as being unlawful. The US military has substantially increased the frequency of its presence missions on, over and under the South China Sea. Between May 2017 and August 2020, the US Navy conducted 24 Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the disputed Paracel and Spratly Island - six times more than during the Obama administration. The Trump administration's tougher South China Sea policy has generally been welcomed by the Southeast Asian claimants, especially its support for their sovereign rights in their exclusive economic zones. However, there is some concern that a US-China military confrontation in the area could embroil the region in an unwanted crisis.

The Trump administration's rejection of multilateralism and its approach to China should remain the most important determining factors in US engagement with Southeast Asia

Overall, America's image in Southeast Asia has suffered over the past four years. In its annual survey of regional elite opinions in January 2020, the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute found that 49.7% had little or no confidence that the US would "do the right thing" internationally, while 77% believed America's engagement with Southeast Asia had declined since Trump took office. Three-fifths agreed that a change of leadership in the November 2020 US presidential election would increase their confidence in America's position in the region.

A second Trump administration, as indicated by the lack of a 2020 Republican Party platform, would likely persist with the same personalised approach to foreign policy and diplomacy, and economic and defence policies. The Trump administration's rejection of multilateralism and its approach to China should remain the most important determining factors in US engagement with Southeast Asia

... contentious areas in US-China relations will remain unresolved - Taiwan, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, unfair trading practices, influence operations, espionage etc - and in all likelihood, will worsen.

A Biden administration and Southeast Asia

Although US party platforms are not meant to be concrete pledges of action, they do give a general indication of the policy directions the administration will take. The Democratic Party platform makes a number of promises on foreign policy:

1. The US will stand up to China over intellectual policy theft and industrial cyber espionage;

2. Alliances are the cornerstone of America's national security and should be repaired and reinvented to deal with new challenges;

3. Democratic values will be at the core of foreign policy (and "Burma's persecution of the Rohingya" will be condemned);

4. America will spend more on diplomacy and public health while maintaining strong armed forces. As the party platform is short on details, it is difficult to discern what the policy implications may be for Southeast Asia.

As there is a general bipartisan consensus on China and the perceived threats it poses to US national security, a major shift in policy on China should not be expected, least of all a return to "engagement" which is now generally seen to have failed to transform China into a more democratic country and a supporter of the rules-based international order. Thus, contentious areas in US-China relations will remain unresolved - Taiwan, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, unfair trading practices, influence operations, espionage etc - and in all likelihood, will worsen.

America's South China Sea policy under Biden will remain unchanged. We can anticipate an increased tempo of exercises with allies and partners, presence missions and FONOPs. The US will continue to provide capacity-building support for the Southeast Asian claimants.

The Biden campaign has promised to revert to the Democratic Party's reserved support for multilateralism as an important tool of American global leadership. Biden has committed America to rejoining the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change "and lead the world to address the climate emergency". He has pledged to rejoin the World Health Organization "on his first day in office". Rejoining the World Health Organization and seeking to revive US global leadership should mean that a Biden administration would be more willing to support a global plan for the equitable distribution of coronavirus vaccines. A Biden administration would likely stop denying new judges to the WTO Appellate Body, and work more closely with the EU, Japan and others to reform the WTO with their shared concerns about China as a major impetus.

Southeast Asian perspectives

Over the past four years, Southeast Asian leaders have adjusted to Trump's mercurial style of leadership. If Trump is re-elected they will continue to work with his administration on a range of economic, political and security issues. ASEAN and Southeast Asian states may become less critical of Trump's continued absences from ASEAN-led meetings and more accepting of lower-level US representation as they have with China and Russia.

Several regional states are likely to welcome a second Trump term, especially Vietnam - which appreciates his administration's harder line on China, especially in the South China Sea - and Thailand which normalised relations with the US after Trump took office.

In the worst-case scenario, if military conflict breaks out over Taiwan, Southeast Asian states may come under pressure to choose sides even if they wish to remain neutral.

However, their foremost concern will be an intensification of US-China rivalry - in trade, technology and in the South China Sea and Mekong region. Although Taiwan is not part of Southeast Asia, it is geographically contiguous. Rising tensions between the US and China over Taiwan would likely have a spillover effect on the region. In the worst-case scenario, if military conflict breaks out over Taiwan, Southeast Asian states may come under pressure to choose sides even if they wish to remain neutral.

Some Southeast Asian countries will hope that the US will join the CPTPP. The prospects of this are not good.

If Biden forms the next administration, Southeast Asian states will hope for three changes in approach and policy:

1. A less transactional approach to bilateral relations.

2. More frequent participation by senior US officials in ASEAN-led forums, especially the EAS.

3. Some Southeast Asian countries will hope that the US will join the CPTPP. The prospects of this are not good. According to the Democratic Party platform, the US will "not negotiate any new trade deals before first investing in American competitiveness at home". Democrat legislators have long been wary of free trade agreements. In 1993, the Clinton administration needed strong Republican support to override Democrat opposition in the House of Representatives to the North America Free Trade Agreement. The Republican members of Congress today would likely be less willing to support any trade deal pushed by a Democrat president. Even the Democratic nominee for the 2016 US presidential election, Hillary Clinton, did not fully support TPP, an initiative of the administration she served in.

Southeast Asian states will be less enthusiastic about a Biden administration if it adopts a strong rhetorical stand on promoting democracy and human rights, as previous Democratic administrations have done. These concerns would be aggravated if a strong proponent of human rights is appointed as secretary of state.

Concerns about America's relative decline against China were prevalent in Southeast Asia before Donald Trump's surprise 2016 presidential victory. Fears about US disengagement from the region and China's more aggressive use of its growing power over the last four years have aggravated these significantly. A second Trump administration or a first Biden administration will find it hard to address these worries but will need to gain greater regional support for US policies on China and efforts to reassert US leadership.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2020/112 "The Trump Administration and Southeast Asia: Half-time or Game Over?" by Ian Storey and Malcolm Cook.

Related: Trump or Biden, the US is on a path of decline | China's preferred choice: Trump or Biden? | To manage Trump the 'destroyer', China needs 'guerrilla' tactics | A win for Biden is a win for China? | Unfavourable views: Southeast Asia's perceptions of China and the US worsen amid Covid-19 | China's Southeast Asian charm offensive: Is it working? | How a Biden presidency can win back lost American influence in Southeast Asia