When a Chinese teapot wants to 'escape from the British Museum'

A short video series featuring Chinese artefacts in the British Museum has gone viral on social media in China, with viewers being moved by the story of a teapot trying to go home to China. But even as critics highlight the heavy sentiment and patriotism in the series, it has prompted calls by China and other countries for the British Museum to return artefacts to their rightful owners.

(Photos: Screen grab from Escape from the British Museum video series, unless otherwise stated)

The most popular film on Chinese social media right now is probably not a star-studded production, but a three-part social media video series totalling less than 20 minutes - Escape from the British Museum (《逃离大英博物馆》).

The short video series aired its first episode on 30 August and its final episode on 5 September; as of 7 September, it has racked up over 290 million views on short video platform Douyin, with related topics viewed over 1 billion times. The series has also garnered over 16 million views on video-sharing platform Bilibili, as views continue to climb.

The two post-90s creators and main actors of the series, who go by their Douyin usernames Jianbing Guozai (煎饼果仔) and Xiatian Meimei (夏天妹妹), saw their fans increase by a cumulative total of over 5 million across various platforms, and were also interviewed by state media CCTV News. On 2 September, before the release of the final episode, China Movie Channel (CCTV6) even praised the motivation and sentiment of the series, noting that it had gone viral.

The story

Through the personification of artefacts at the British Museum, the short video series tells the story of a jade teapot that "escaped" and encountered Chinese reporter Zhang Yong-an in the UK. The pair then returned to China, where the teapot passed on letters from other Chinese artefacts at the British Museum.

The first two episodes of the series, at just over two minutes and four minutes long respectively, were released on two consecutive days and mainly depicted the daily life of the two protagonists in the UK. Through various sentimental details and foreshadowing, the series piqued the curiosity and anticipation of the Chinese audience.

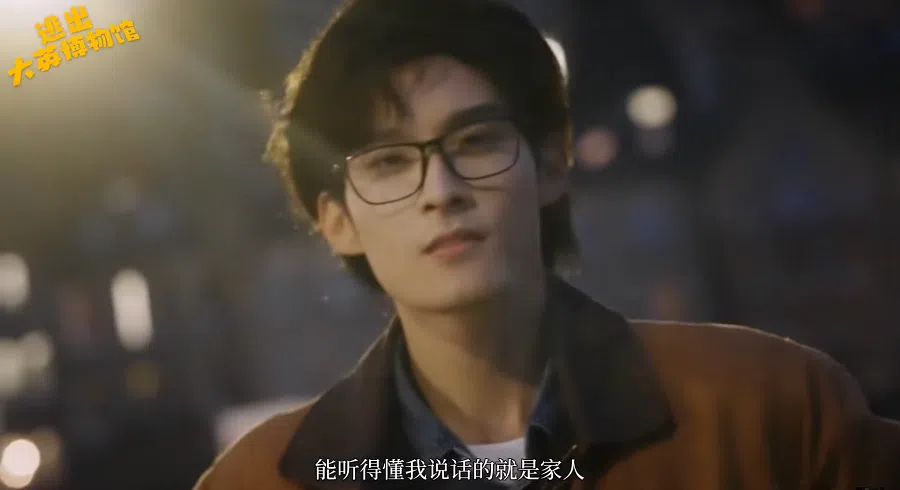

For example, the jade teapot played by Xiatian Meimei says she cannot find her way home and asks if Zhang, played by Jianbing Guozai, will bring her back to China; many Chinese netizens were also touched by memorable lines such as "anyone with black eyes, yellow skin, and who understands what I say is family".

...she pulls out a thick pile of letters, seeks out the "relatives" of the other exhibits at the British Museum, reads them the letters, and returns to the UK.

After piquing viewers' interest, in the finale, the main characters return to China, where they tour the country and experience local life, then head to a museum. However, while many netizens speculated that the teapot would seek help from Chinese authorities to rescue the other artefacts, she pulls out a thick pile of letters, seeks out the "relatives" of the other exhibits at the British Museum, reads them the letters, and returns to the UK.

In the video, the teapot says she is going back to the UK because the Chinese people "do not sneak around, and will come home one day gloriously with head held high". Countless Chinese netizens heaped praises on this line that exemplified the "bearing of a great nation".

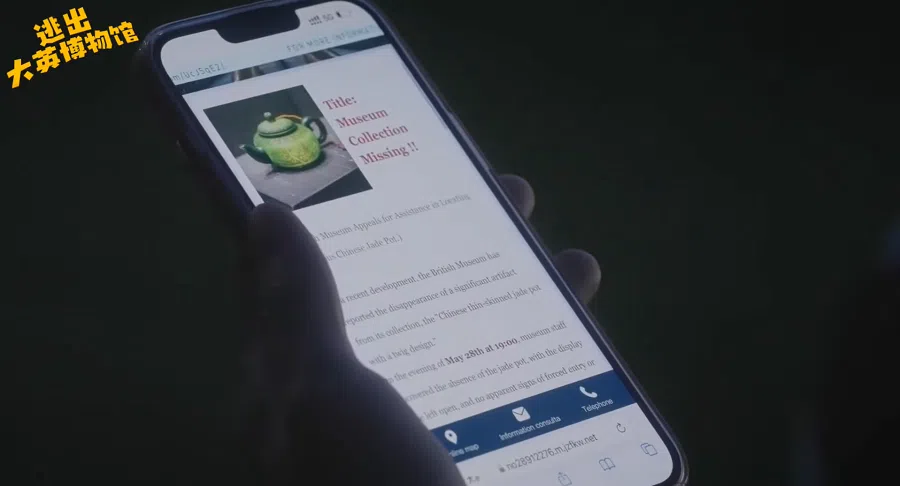

At the end, the video series rides on the popular news of the thefts at the British Museum, with Zhang becoming a news anchor and reporting on the sudden disappearance and recovery of artefacts from the British Museum.

The plot is not complicated, without too many plot twists, and does not delve into logical details. It brings out the experience of both protagonists in the style of arthouse vignettes, using voiceovers and shots of museum artefacts. In addition, as the letters are read aloud, the museum artefacts are given human characteristics, captivating the audience with memorable lines.

... with its rich detail, the production might even be considered a cultural propaganda film.

Not a masterpiece?

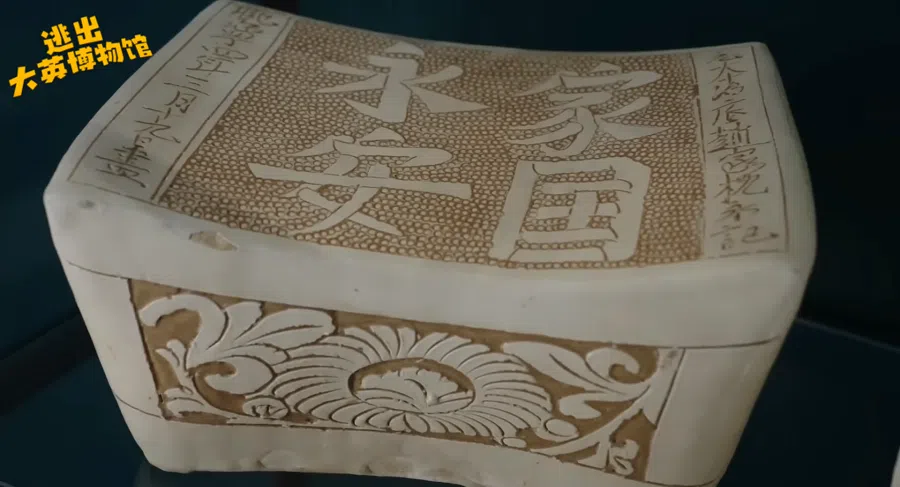

As listed by Chinese netizens and the media, the series featured about a dozen cultural relics, including a terracotta figure of a guqin player (琴师陶俑), a Tang dynasty three-colour horse (唐三彩马) and a bronze pot with dragon and tiger carvings (龙耳虎足铜方壶) from a museum in China, as well as a Jin dynasty three-colour Luohan figure (金代三彩罗汉像), a Ming dynasty glazed ceramic tiles with dragon carvings (明代龙纹琉璃砖墙), a porcelain pillow with the inscription "家国永安" (Jia Guo Yong An, meaning everlasting peace in the family and state), a wooden figure of the Bodhisattva Guanyin (木雕观音), and a carved ivory ball (象牙鬼工雕球) from the British Museum. Of course, this is just the tip of the iceberg among some 23,000 artefacts from China in the British Museum.

Apart from the museum, the two protagonists also watched the flag-raising ceremony at Tiananmen Square and saw the giant pandas in Chengdu, along with experiencing traditional activities such as taichi, Chinese opera, sugar blowing, and molten iron throwing - with its rich detail, the production might even be considered a cultural propaganda film.

As expected, the series received mostly positive reviews. Many Chinese netizens commented on social media and movie review sites that they were "in tears", moved by the genuine sentiments shared among the cultural relics, between the relics and the Chinese people, and the sentiment for family and country. They also heaped praises on the clever ending and the magnanimity it portrayed.

Many netizens also took it upon themselves to explain certain details - for example, the main jade teapot character is actually a teapot decorated with a Mughal style pattern of lotus flowers and entangled branches of Medinilla magnifica that the British Museum had purchased in 2017. It is a modern object and not an ancient relic, which is why she is "simple and trusting and knows her way home".

Then there is the fact that the scene was set in Henan Museum because of a Chinese poem: "If friends and family from Luoyang (in Henan province) ask about me, tell them that my heart is still as pure as ice in a jade teapot (洛阳亲友如相问,一片冰心在玉壶)."

State media China News (中国新闻网) published an article on 6 September praising Escape from the British Museum as a work of creativity and depth, with a strong sense of family and country. It noted that short videos can also portray broad perspectives, and that young social media influencers of the new era have pure passion and dreams, and are willing to work hard.

However, there were also critical voices on the Chinese internet. Some critics felt that regulating the country's cultural relics protection mechanism, enhancing the standard of museum management and then recovering artefacts via official channels would be more practical than stirring up people's patriotism and devotion to the country through film production.

Other netizens pointed out that the series is just a sweet romantic drama in the guise of a patriotic production, as it overplayed the emotions between the protagonists, with flaws in character design and filming; it is not a masterpiece, and it only went viral because it selected the right subject.

... the success of the material also had everything to do with hitting the right time, place and people in terms of publicity.

Right time, right place, right people

Personification is not a new concept - CCTV film series National Treasure (《国家宝藏》) also used the technique to tell the story of displaced cultural relics. However, the difference is that this video series was released right when some 2,000 artefacts had been stolen from the British Museum.

The incident prompted Hartwig Fischer to resign as British Museum director on 25 August, along with requests from Greece, Egypt and Nigeria for the British Museum to return their artefacts. On 28 August, Chinese state media Global Times posted a strongly-worded commentary requesting the British Museum to "return all Chinese cultural relics... to China free of charge", as the topic became the top search on Weibo at one point.

The popularity of Escape from the British Museum also attracted attention in the UK press. While there was generally little criticism of the video series itself, the BBC and other media outlets pointed out that Chinese officials have in recent years placed increased emphasis on cultural heritage and ownership as a means of reinforcing nationalist sentiments and promoting national identity.

The examples cited by the BBC included the boycott of luxury brand Dior when it was accused of culturally appropriating China's traditional horse-face skirt for an outfit last year; also, early this year during the controversy over "Lunar New Year", the English translation used for nongli xinnian (农历新年), a vlogger visited the British Museum saying that the Chinese artefacts must be homesick, which prompted this short video series.

Escape from the British Museum stood out from similar productions because the creative team spent months of effort in polishing the script and shooting in multiple locations, while the success of the material also had everything to do with hitting the right time, place and people in terms of publicity.

The right time was launching the series just when the British Museum's theft scandal was gaining attention on Chinese social media platforms; the right place is the fact that Douyin's massive user base helps the rapid dissemination of short videos on the internet; most importantly, the right people is the Chinese people, who do have feelings for Chinese artefacts that are overseas and anticipate their return, while the authorities also want to add value to the videos and strengthen such national sentiments.

Where historical relics belong depends on the opinions of conservation experts and diplomatic manoeuvring between countries. Personal sentiments or a short film may have little power to resolve the issue. By highlighting the overseas artefacts and the discussion surrounding them, the short film has brought attention to the issue and hopefully, it will not just be a one-off or one-sided discussion.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "《逃出大英博物馆》走红背后".

Related: Blue and white porcelain in Istanbul's Topkapı Palace Museum | The book box: A cultural journey from Geylang to China and back | Chinese films hit it big during CNY, but is it enough to save the industry? | When neighbours disagree: Did China 'steal' South Korea's culture and historical memory?