Chinese provinces' battle for talents and workers after Chinese New Year

Zaobao journalist Meng Dandan looks into the current shortage of workers in various areas of China, especially in the labour-intensive manufacturing sector. Why is it so difficult to hire and retain workers, and what does this mean for the world's factory and the global supply chain?

"Hiring workers is difficult these days, even short-term ones," Li Hongyao said wearily as she packed rabbit plush toys into small parcels to be couriered. Li is the owner of a soft toy e-commerce store at the Rongcheng trading centre in the Xiong'an New Area of Hebei province.

Just after Chinese New Year, Li began recruiting toy packers through word of mouth and lifestyle media platforms. There were no takers even after more than a month so she had to do the work herself. Li offered a generous salary of 4,500 RMB (US$646), which is at least 10% higher than the average salary at Rongcheng.

Hiring woes following Chinese New Year

While inland towns in northern China are finding it difficult to recruit, major coastal industrial provinces are having an even harder time.

Huang Guoqing, the general manager at a magnesium and aluminium alloy die-casting plant in Zhuhai, Guangdong province, told Lianhe Zaobao that in recent years, the labour shortage has been the biggest challenge in resuming business after Chinese New Year. With the lifting of pandemic measures, the shortage is even more pronounced this year.

He said, "We expected this. Before the Chinese New Year, the factory offered each worker an additional half-month salary if they came back to work after 6 February (the last day of Chinese New Year), but till now, some people have not returned."

The company Huang works for has been around for over ten years, and its products are mainly used in cars, aircraft and home appliances, with 80% sold to Europe and the US, including several Fortune 500 companies.

The company currently has about 200 staff with an average age of above 35, most of whom have over ten years of work experience. He said, "The older workers are familiar with the production technology and have their families with them, so they would not easily change jobs. The ones we lack most are young rank-and-file workers."

As various regions accelerated their economic measures, a large number of key projects have started at the same time, consumption is gradually picking up, and the demand for labour in the service and manufacturing industries has greatly increased...

Three years of pandemic controls and a declining property market have dealt China's economy its hardest blow in a decade. Last year, China's economy grew only 3%, much lower than the 5.5% target.

In late 2022, the Central Economic Work Conference gave clear signals of boosting the economy and confidence to get China's economy back on track, emphasising efforts to grow domestic demand and prioritising restoring and increasing consumption.

As various regions accelerated their economic measures, a large number of key projects have started at the same time, consumption is gradually picking up, and the demand for labour in the service and manufacturing industries has greatly increased, exacerbating the labour shortage and hiring difficulties following Chinese New Year.

To recruit and retain workers, companies would normally have to boost benefits and pay to maintain operations. However, some small- and medium-sized enterprises are already finding it tough surviving under the current economic situation, and could ill afford to bridge the employment gap with better benefits and pay.

Talent crunch in new energy sector

A financial head of a private company in Qingdao, Shandong province, that produces battery packs said that the company was set up less than four years ago and is still in its infancy with less than 100 employees, far below the original target of 300 employees. He said, "In fact, we have been hiring all year round, but the economy is lacklustre and the company lacks profits to offer higher salaries. If the company had performed better, it would definitely offer a more competitive salary, and hiring would be much easier."

He lamented, "It will be harder to hire this year, as talents in the new energy sector are also in demand."

"New energy" appeared repeatedly in the work reports of 31 local governments this year, and the new energy sector is seen as a rising strategic sector to drive local economies in the transition from old to new energy. Various regions are ramping up new energy projects, worsening the talent shortage in the sector.

According to the blueprint for talent development in the manufacturing industry released by agencies including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the energy conservation and new energy sectors alone lack 680,000 talents.

"Post-80s and post-90s people are more relaxed. They are willing to earn less, rather than do tedious work." - Li Hongyao, owner of soft toy e-commerce store

Young people unwilling to work in factories

Companies that aren't performing well will naturally not be able to attract people with higher pay, and the labour shortage could worsen. While Huang Guoqing said frankly that salary is becoming less of a pull factor for migrant workers, companies are also facing great pressure and cannot provide more.

He said, "Ordinary factory workers in Zhuhai earn an average monthly pay of about 5,000 RMB to 6,000 RMB, and companies spend about 10,000 RMB in labour costs. Workers who go back to their hometown would get roughly the same amount, and some might not come back after Chinese New Year."

Li Hongyao believes that her difficulty in hiring toy packers is not caused by the salary or the poor economy. On the contrary, this year she saw an increase in orders for soft toys after Valentine's Day on 14 February, which would otherwise have trended downward in previous years.

She feels that the career ideals of the young generation of Chinese are the reason for her hiring woes. "Post-80s and post-90s people are more relaxed. They are willing to earn less, rather than do tedious work."

She explained, "Packing toys may sound easy, but each person has to fulfil at least 500 orders a day and do everything themselves, from getting the stock to putting them in bags. The nearby villagers have received compensation for housing relocation, so they are even less willing to do such tedious work for a few extra hundred dollars."

Huang Guoqing's factory in Zhuhai encountered a similar situation last year. The factory hired two young workers aged below 25, and both left within less than six months. Huang said one felt that the factory was too noisy and the work environment was no good, while the other complained that they could not find a partner because at least 95% of the workers in the factory are men, with very few young women.

Huang is well aware of the reason why the factory can't retain young people. He said, "The work is monotonous and boring, and you could earn more in the delivery sector, so of course young people don't like it."

If China wants to stay competitive in the global manufacturing sector, it will have to engage in industrial upgrading and "turn nearly 200 million people with tertiary education into a new demographic dividend".

With young Chinese unwilling to take low-paying intense jobs, will the labour shortage and hiring difficulties cause China, the world's factory, to lose its competitiveness in labour-intensive sectors?

Xu Hongcai, deputy director of the Economic Policy Commission at the China Association of Policy Science, said that China will not lose its advantage in the manufacturing sector in the short term, but the sector will continue to shift towards Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines.

If China wants to stay competitive in the global manufacturing sector, it will have to engage in industrial upgrading and "turn nearly 200 million people with tertiary education into a new demographic dividend".

... an increasing number of migrant workers have chosen to stay in their hometowns after Chinese New Year due to the new job opportunities in China's rapidly developing midwestern region, improved rural infrastructure and the local governments' support measures.

Migrant workers working in hometowns

While China's economy and society are getting back on track after the three-year-long pandemic, the prolonged lockdowns in 2022 have badly affected the economies of eastern coastal cities and made it tougher for migrant workers to remain in the big cities.

At the same time, an increasing number of migrant workers have chosen to stay in their hometowns after Chinese New Year due to the new job opportunities in China's rapidly developing midwestern region, improved rural infrastructure and the local governments' support measures.

Last October, 37-year-old Chen Yiwei left Shenzhen and returned to his hometown in Guang'an, Sichuan. He is now working as a CNC machine operator at an auto parts processing plant about ten kilometres from his home.

He told Zaobao, "I could earn about 6,000 RMB a month if I worked full 12-hour shifts every day." He added, "I can drive to and from work every day and no longer need to rent an apartment. The cost of living is also much lower, and it's not much different from what I earn in Shenzhen. But I feel much more secure now and don't have to worry about changing jobs all the time."

Chen had worked in Shenzhen's food and beverage (F&B) industry for over a decade before returning to his hometown. His last job was in product development at an enterprise specialising in ready-to-eat meals. Although he earned a decent salary, he did not feel a sense of belonging, especially during the pandemic when the F&B industry was badly hit and enterprises were shuttered. During that time, Chen was forced to constantly switch jobs.

He recalled, "Many restaurants couldn't survive Covid-19 then... I also had to rent a new apartment whenever I changed jobs. Moving is extremely troublesome and tiring." Thinking back on how difficult life was in Shenzhen last year, Chen decided to work in his hometown instead.

After experiencing the uncertainties brought about by the pandemic, some young workers are no longer bent on leaving their families behind to earn more money in the big cities.

Thirty-three-year-old Su Lili returned to her hometown in Anhui's Suzhou during the second year of the pandemic, and has been working at an automation workshop of a power tool processing plant. She takes home a piece-rate wage like Chen, and could earn up to 5,000 RMB a month if she clocks in 12 hours of work every day.

Apart from being slightly bothered by the fact that her "hands are always drenched in engine oil" because of her factory job, she is relatively satisfied with her current income and state of life.

She told Zaobao, "I can go home every day to spend time and eat delicious food with my children. I can also bring them out to play on my two off-days a month."

Data from China's National Bureau of Statistics showed that there were 296 million migrant workers in 2022, an increase of 1.1% year-on-year. While there is no official data on the proportion that have chosen to remain in their hometowns instead of returning to the coastal manufacturing hubs, which account for one-third of global manufacturing output, it is clear that more migrant workers now prefer to work in their hometowns.

Although there are still approximately 48 million more migrant workers than workers who are based in their hometowns, the growth rate of migrant workers (0.1%) is still far less than those working locally (2.4%). Since 2015, the growth rate of migrant workers (0.28%) was already less than those working locally (1.99%).

... officials from Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu and other regions have led delegations on chartered planes, trains and cars to Guizhou, Guangxi and other massive labour powerhouses to grab talent...

Battle for talents among provinces and cities

As Chinese workers are more inclined to work in the vicinity of their hometowns, the labour dividend is shrinking as well. Following China's post-pandemic reopening and the overall drive to put the economy back on track, China's manufacturing centres and eastern provinces where demand for labour is particularly strong are desperately fighting to stabilise the workforce, with local governments and enterprises each going all out to battle for talent.

The richer eastern provinces quickly offered cash incentives and subsidies for key enterprises, while officials from Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu and other regions have led delegations on chartered planes, trains and cars to Guizhou, Guangxi and other massive labour powerhouses to grab talent as early as before the Spring Festival celebrations.

Some enterprises desperately in need of workers to fulfil orders have turned to creative tactics to attract talent.

In Zhejiang's Wenzhou, which is known for its well-developed private economy, employees are rewarded 1,000 RMB in cash for referring new hires to the enterprise. Some enterprises in Zhejiang's Yongkang are even offering attractive consumption vouchers to retain their migrant workers. Lucky winners of "golden consumption vouchers" can almost pay for a brand-new car.

Some local governments and enterprises play the "warm and friendly" card to grab talents by offering accommodation for migrant couples. Some also provide a plethora of employee benefits such as team building programmes, training and travel subsidies to attract young workers.

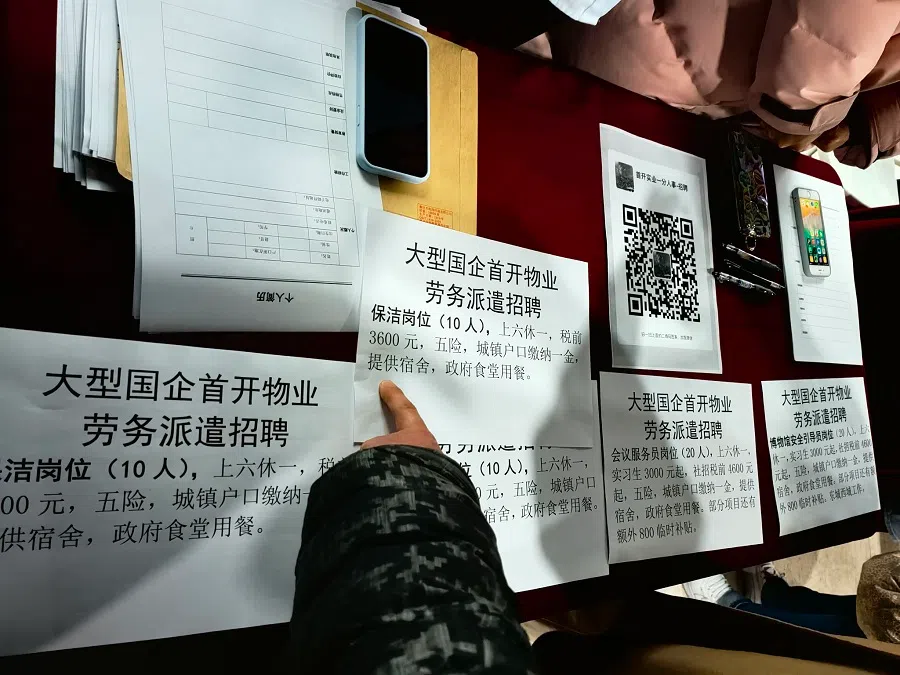

At the job fairs held in February in Tongzhou (Beijing's sub-centre) and Dongcheng (Beijing's urban core), I found that numerous enterprises tried to attract more eyeballs by highlighting the fact that they are "state-owned enterprises", and that employees are allowed to eat at "state-owned canteens". They also promoted other employee perks such as birthday and holiday vouchers, as well as gifts.

He [Huang Guoqing] also plans to invest in another automated robotic arm to further reduce labour costs in the long term.

Other enterprises also indicated that they have long-term business relationships with state-owned enterprises and other institutional units, highlighting job stability to attract job seekers. Several enterprises have also relaxed the age limit of applicants.

Apart from organising frequent online and in-person job fairs, Beijing has even rolled out a subsidised housing programme for people returning to the city after the Spring Festival holidays to ease the pressure of high housing prices. Under the programme, 52 housing agencies will offer 530,000 accommodations to new residents, youths and essential workers who keep the city running, along with various subsidies such as discounted rental commission and no deposits. The programme is aimed at encouraging young and migrant workers to return to work in Beijing after the Spring Festival holiday to avoid any disruptions to the city's operations.

Robots to the rescue?

Nonetheless, the labour shortage has yet to affect the productivity and operations of China's labour-intensive provinces. More than 90% of migrant workers have returned to work in Jiangsu, Guangdong and Shanghai, significantly curbing the labour shortage issue.

Huang Guoqing said that while some employees have yet to return to work, the factory is generally operating normally. He also plans to invest in another automated robotic arm to further reduce labour costs in the long term.

On the other hand, Li Hongyao anxiously awaits interested toy packers as she is exhausted from consecutive days of overtime after the Spring Festival. She said that she would consider increasing the salary offer if she is still unable to hire anyone, since she is encouraged by the massive number of orders she recently received.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "用工荒招人难 中国"抢人大战"".

Related: China's youths are feeling the pressure from low wages | Post-00s youths want to rewrite workplace norms in China | Why China has too many graduates and not enough skilled workers | Plight of China's new generation of young migrant workers highlights pitfalls of labour reforms | 200 million Chinese are in flexible employment. Is this their choice?

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)