Copying is a virtue in Chinese ink painting

Temporary orders to halt the KAWS public art installation exhibition led Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre CEO Low Sze Wee to ponder the copyright issues of Chinese ink paintings. He notes that many of Singapore's first-generation artists like Chen Wen Hsi and Fan Chang Tien were educated in Shanghai in the 1920s and were deeply influenced by the Shanghai School. Copying was a common mode of learning, and students like Henri Chen Kezhan and Chua Ek Kay did their best to copy the works of their teachers. While they eventually developed their own styles over time, Low says it could be argued that their achievements were made possible by their formative years spent on copying.

On 13 November 2021, one day before the much-anticipated KAWS public art installation was due to open in Singapore, its organisers were served a court injunction demanding the exhibition's closure and the suspension of all merchandise sales. Among other issues, the plaintiff alleged that the organisers had breached the former's intellectual property rights.

Whilst specific details of the court case are not yet known, the legal principles of intellectual property rights are clear. Many countries, like Singapore, have established legal frameworks to protect the rights of those who create original works of art such as paintings or sculptures. These rights include the right of reproduction. Hence, whenever someone wishes to make use of an artwork image, the artist's permission needs to be sought. By granting such rights, the law hopes to reward artists economically and incentivise them to create more works in the future for the public to enjoy.

At the same time, the law also recognises valid situations when such rights should be limited for the larger public good, for instance, in permitting copies for non-profit educational purposes. Copies are also allowed if done for a limited and transformative purpose such as to comment upon, criticise or parody a copyrighted work. This is known as the defence of fair use. In addition, a copyrighted work is only protected for a specific period (generally the length of an artist's life plus another seventy years), after which the work enters the public domain. These are different ways in which copyright laws try to balance the rights of artists with those of society at large.

Many ink painters today do not regard anything wrong in copying the works of others. For centuries in China, copying had been a commonly accepted way of learning how to paint.

Copying in art

However, such modern legal frameworks often find it challenging to take longstanding cultural traditions into consideration. The practice and transmission of Chinese ink painting is one such example.

Many ink painters today do not regard anything wrong in copying the works of others. For centuries in China, copying had been a commonly accepted way of learning how to paint.

This was because copying was a proven method of studying how earlier artists translated the three-dimensional world onto the two-dimensional surface of a painting This was facilitated by the fact that the simple tools used for such paintings (ink and colour pigments applied with a brush on paper or silk) had remained largely unchanged over the centuries.

Beginners learn by copying the brushwork and composition of their teachers or from studying extant masterpieces. Over time, they build up a repertoire of techniques and skills, ranging from how to handle the brush to how much ink and water to use on different types of paper. Through such copying, students eventually develop powers of close observation, dexterity in using the brush and a strong understanding of how master artists had composed their paintings to create different visual effects.

Copying in Singapore

Copying also ensured transmission of the Shanghai School painting tradition from China to Singapore during the 20th century.

The Shanghai School first emerged in the 19th century with the opening of the treaty ports by Western powers after the Opium War (1839-1842). As a result, Shanghai became the richest port city in China. With a rising mercantile class, the demand for art as status symbols surged.

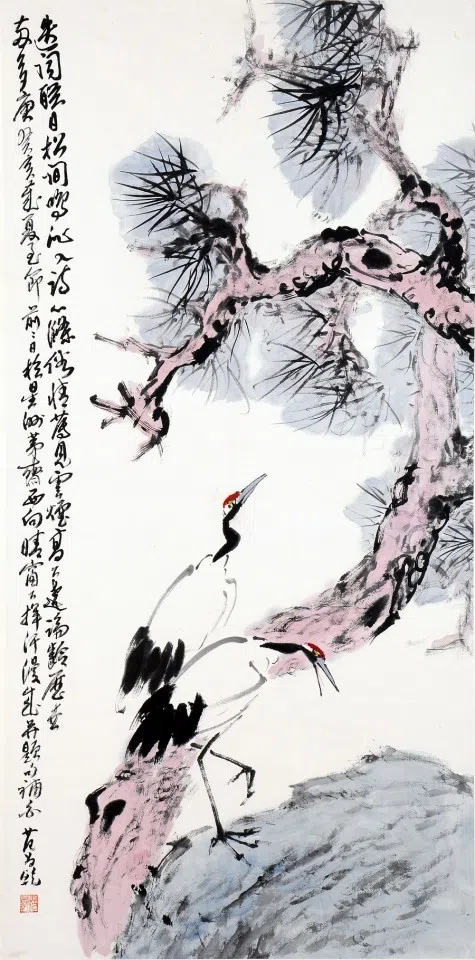

The cosmopolitan city attracted the best artistic talents from all over China who developed commercially popular styles that came to be known as the Shanghai School. Their works were characterised by rich colours, bold calligraphic strokes, lively compositions and accessible subjects like birds and flowers, or themes drawn from mythology, history, and popular fiction.

Many of Singapore's first-generation artists like Chen Wen Hsi and Fan Chang Tien had been educated in Shanghai in the 1920s and were deeply influenced by the Shanghai School. When they eventually settled down in Singapore after the end of the Second World War, they also brought this painting tradition with them and transmitted it to their students in Singapore.

One well-known example was Fan Chang Tien and his students such as Henri Chen Kezhan. Rather than enrolling in a formal art school, Chen chose the traditional route of learning ink painting from the senior artist Fan. This involved one-to-one instruction where Fan demonstrated the techniques for painting different subjects.

Chen recalled that his teacher often emphasised close observation and mastery of traditional techniques. Chen was not allowed to bring the demonstration pieces back home. Instead, Fan insisted that Chen pay close attention to his demonstrations and then practise the techniques at home, based on what he had absorbed from class. He also made Chen compare and assess the quality of different paintings by various artists. All these were done to train Chen to think for himself and develop a sound understanding of the qualities of good paintings.

However, teachers like Fan understood that copying was a means to an end, and not the end itself. Having a good grasp of painting techniques was insufficient. It was equally important for artists to understand how to apply their knowledge to reality. Hence, studying nature was also a key ingredient in artmaking.

Every aspect of nature - be it mountains, rivers, flora, or fauna - was different. Its appearance to the human eye would also differ, depending on the season, weather and even time of day. The potential permutations were limitless, and therefore, an artist needed to know how to apply his acquired techniques flexibly. He might even need to invent new brushstrokes to capture particular forms, like the Song dynasty artist Mi Fu who was credited with introducing a technique of using moist washes and horizontal texture strokes (called "Mi dots"), to depict the misty rivers and hills of the area where he lived.

Once an artist has attained a solid foundation in painting techniques and a deep understanding of his subject matter, he was then expected to develop a personal language that was a synthesis or re-interpretation of past styles, and a reflection of his personality, temperament and character.

Once an artist has attained a solid foundation in painting techniques and a deep understanding of his subject matter, he was then expected to develop a personal language that was a synthesis or re-interpretation of past styles, and a reflection of his personality, temperament and character. This explained why Fan's students eventually developed styles markedly different from their teacher's.

This view was also echoed by another of Fan's students, Chua Ek Kay, who observed that whilst Fan taught the basics of Shanghai School painting to his students, he also encouraged them to develop their own styles. Chua likened this approach to Qing dynasty artist Shitao's theory of "the method of no method" (无法之法, 乃为至法). In other words, once an artist had mastered the tradition, he needed to transcend it, to overcome the deadening effect of orthodox techniques.

Developing one's own style

The difference between teacher and students was amply demonstrated through their artworks. Fan was primarily known for his paintings executed with confident brushwork, usually paired with original poetry written in fluid running script (xingshu). His subjects often included flora and fauna, particularly those infused with traditional cultural symbolism such as bamboo and lotus. For students like Chen and Chua, whilst their early works looked like their teacher's, they eventually developed radically different styles and subject interests from the late 1980s onwards, after Fan had passed away.

By then, Chen's paintings had fewer explicit references to the natural world and became more abstract. Instead of describing form or using calligraphic linework, Chen was more focused on complex manipulations of colour and brushwork to convey sensations and movement. By the late 1980s, Singapore's post-independence policies had led to rapid urban redevelopment. Chua was struck by an acute sense of loss when encountering the city's old shophouses in various states of transformation. That led him to create a series of ink paintings of local street scenes, filled with a sense of melancholy and passing of time.

Both Chen and Chua are regarded as important Singaporean artists today. It could be argued that their achievements were made possible by their formative years spent on copying.

During the early days when mechanical reproduction was not available, the only way that masterpieces could be widely circulated and studied was through hand-made copies.

Value in copying

Copyright laws aim to protect originality and promote innovation in artmaking. Consequently, copying is discouraged. However, as illustrated by the example of ink painting, techniques and styles are understood, practised and transmitted from one generation to the next by copying. Hence, there is value in allowing or even encouraging artists to copy the works of others.

Moreover, copying played an important role in the writing of art history in China. During the early days when mechanical reproduction was not available, the only way that masterpieces could be widely circulated and studied was through hand-made copies. Hence, our understanding of Chinese art history today has been partly shaped by being able to refer to surviving copies of long-lost masterpieces. For instance, even though none of the famous 4th century painter Gu Kaizhi's original artworks have survived to the present, we still have some idea today of what they might have looked like, thanks to the copies made by later artists.

In a society where much respect is accorded to seniority and ancestry, Chinese artists have long been regarded as custodians and transmitters of culture. Hence, creating a work that refers to the past, especially the styles of great masters, signals an artist's intent to be included as part of an illustrious lineage.

In the context of Chinese ink painting, reverence for the past and paying homage to tradition are valued traits. How could these be protected or even promoted by modern laws? As the practice of ink painting evolves, and more intellectual property rights disputes (like the KAWS case) arise in the future, these are questions worth pondering over.