Breaking Hell’s Gate: The vanishing rituals of Taoist funeral priests

Cantonese Taoist funeral priests, or nam mou sifu, were known for their physical feats such as walking over hot coals, plunging their hands into boiling oil and climbing knife ladders. While today’s priests may no longer do all this, it is still a demanding job that not everybody can do. Lianhe Zaobao lifestyle correspondent Tang Ai Wei speaks to one of the last nam mou sifu in Singapore.

(Photos: Long Kwok Hong/SPH Media, unless otherwise stated)

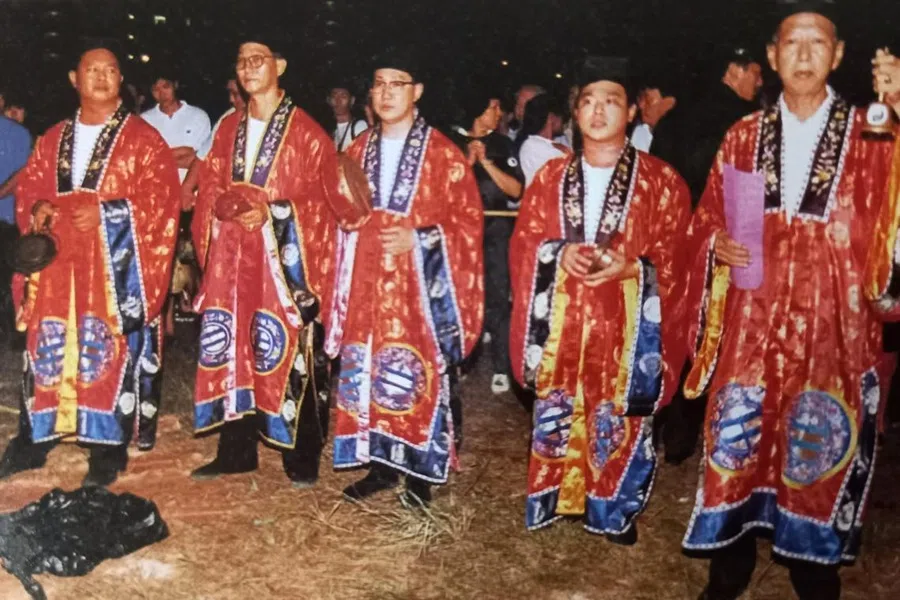

The Last Dance (《破·地狱》), a Hong Kong drama film released in November 2024, has sparked public interest in Cantonese Taoist priests in charge of conducting funeral rituals — commonly referred to as nam mou lo (喃呒佬). They actually dislike this name, finding it disrespectful, and prefer to be called nam mou sifu (喃呒师傅) or scripture-chanting masters instead.

Woo Ying Poh, a 75-year-old third-generation nam mou sifu, sighed, “I fear I may be the last of the line.”

An extremely challenging deliverance ritual

Back then, Woo’s grandfather, Woo Fa Zhang, came to Singapore from Guangdong’s Sanshui with his son Woo Yue Meng, and settled in Tofu Street — the area around what is now Chinatown Point — where many fellow Sanshui people lived. Woo Ying Poh never met his grandfather; from as far back as he can remember, there was only his father’s busy silhouette in Taoist robes.

In the second ritual, the master would plunge his bare hand into a pot of boiling oil to retrieve coins placed inside.

Tofu Street was home to many Samsui women (Chinese immigrant labourers) and majie (domestic helpers), and nearby Upper Pickering Street, with its nine-storey residential flats, was infamously known as “Suicide Street”. Woo Ying Poh told Lianhe Zaobao that back then, while there were many nam mou sifus from Guangdong, it was the Sanshui masters, in particular, who had a unique deliverance ritual for souls who died unnatural deaths to cleanse their sins and guide them to peace.

The first ritual involved the master walking barefoot over a bed of red-hot burning coal, more than a metre long. The deceased’s son would follow behind, carrying the ancestral tablet. Families scared to do so would circle around instead. In the second ritual, the master would plunge his bare hand into a pot of boiling oil to retrieve coins placed inside. The third ritual saw the master climb barefoot up a towering knife ladder two to three stories high. Each step of the knife ladder was lined with joss paper. As the master stepped onto it, the paper split cleanly in two, proof of the blades’ razor-sharp edges.

Woo Ying Poh’s father and elder brother were highly skilled and could perform all three of these demanding rituals. He admitted that he was never able to master them himself. Until now, he has yet to see any other nam mou sifus perform them either.

He and his father and brothers often performed deliverance rituals to guide the souls of lonely, helpless Samsui women and majie, as well as other fellow Cantonese immigrants.

From several tens to hundreds of dollars

Woo has six elder brothers and a younger sister. Only he and his fifth and sixth eldest brothers inherited their father’s mantle. “I wasn’t particularly interested at first, and even went around fixing water pipes with my second brother,” he recalled. “It wasn’t until I was 22 that my mother asked me to join and help out.” He spent a year learning — not only memorising scriptures but also grasping how to chant while performing funeral rituals.

He and his father and brothers often performed deliverance rituals to guide the souls of lonely, helpless Samsui women and majie, as well as other fellow Cantonese immigrants. Back then, they charged anywhere from several tens of dollars to about S$100 per ceremony. After Tofu Street was demolished in the 1970s, Woo moved to the Redhill area. He later apprenticed under a Maoshan master to learn exorcism, and the use of talismans to ward off misfortune, offering solutions for his clients’ various needs.

In the past, bereaved families would approach nam mou sifus directly, who would then refer them to undertakers. Today, the process has reversed, with nam mou sifus taking on a more passive role. Undertakers, based on the family’s wishes, often recommend Buddhist rites when a simpler ceremony is requested. Woo pointed out that Taoist rituals can be just as simple — the deceased can be cremated right after the master has opened the way. Reflecting on how funeral practices have changed, he said, “Funerals used to last much longer, giving us more breaks to rest in between. Now, with shorter wake periods, the rituals are more compressed and fast-paced.”

Last three standing

Woo’s two elder brothers passed away in 1990 and 2023 respectively, leaving him the last in the family still in the line of work. Today, there are only about 20 nam mou sifus left in Singapore who chant in Cantonese, aged from their 50s, up to 80.

Each funeral ritual requires at least four people: a main ritualist who sets the pace of the ceremony, along with three musicians. Feeling his age, Woo rarely takes on new assignments or leads ceremonies anymore, but now mostly serves as a musician or assistant.

With younger generations unwilling to take up the mantle, Woo likens himself and his peers to the “last generation of nam mou”. Although it saddens him, there is little he can do.

With younger generations unwilling to take up the mantle, Woo likens himself and his peers to the “last generation of nam mou”. Although it saddens him, there is little he can do.

A wedding from a funeral

These days, Woo spends time with his wife, Tan Mong Fai, 57, taking leisurely strolls with their pet bird. Tan first met Woo during her father’s funeral, where he was conducting the ritual. “I’m 18 years younger than him. My dad brought us together. We got married just over a year after we met,” Tan said with a smile. Woo describes his wife as his “white cane” (盲公杖), someone who offers him guidance and support in life.

After watching The Last Dance, many people have asked Woo how accurate the film’s depiction is. His usual reply is: “They consulted experts while filming. Some are real and some dramatised — believe it, and it becomes real.”

In the past, nam mou sifus routinely learned the “Breaking Hell’s Gate” ritual (破地狱) and performed it if the family requested it and was willing to pay extra. “Now,” Woo said, “including myself, there are only three masters left in Singapore who still know how to perform it. The youngest is nearly 60. As for me, I can no longer do the jumping.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “末代喃呒师傅 破地狱本地或成绝响”.

![[Big read] Love is hard to find for millions of rural Chinese men](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/16fb62fbcf055b710e38d7679f82264ad682ce8b45542008afeb14d369a94399)

![[Big read] China’s 10 trillion RMB debt clean-up falls short](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/d08cfc72b13782693c25f2fcbf886fa7673723efca260881e7086211b082e66c)