Jiangnan cuisine: How the ancient literati wrote about it [Eye on JiangZheHu series]

Jiangnan cuisine shot to literary prominence in the 11th and 12th centuries when Song dynasty elites moved from the capital of Bianliang to Lin’an, today’s Hangzhou. Since then, Jiangnan cuisine has captivated many literati epicures including Qing dynasty poet, Yuan Mei. Academic and food writer Thomas DuBois explores the gastronomical charm of that era.

Anywhere in the world, a well-prepared dish will elicit praise and admiration, but in China, it may also inspire a poem, a painting or a heated discussion of history. Or perhaps all three. For China’s imperial-era literati, fine cuisine was more than gustatory refinement, it was also a chance to revel in a profound culture of texts.

China’s long tradition of food writing stands as a distinct genre, one that combines medicine, literary tidbits and gastronomic appreciation.

Novelists use food to dress a scene. Poets set a table to serve as a metaphor for loss, the passing of time or life’s simple joys. Others pen odes of praise for the foods themselves. In four memorable lines, Southern Song poet Fan Chengda (范成大 1126-1193) immortalised the fleeting memory of an elegant meal: a simple soup composed of two ingredients —“taro like freshly congealed butter” (毡芋凝酥) and “yams like cut jade” (土薯割玉).

“Red silk” (红丝) was a steamed pudding made from sheep, pig and chicken blood. “Jade chess pieces” (玉棋子) were small rice flour cakes fashioned like the flat pucks shapes used in the Chinese game of Go.

Fan was one of many literary greats to hail from Jiangnan, the wealthy and cultured region spanning Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces. On the page, Jiangnan was a centre of refined literary culture. At the table, its many local cuisines are marked by elegant and sophisticated kitchen techniques.

Song elites dine in Hangzhou

Jiangnan cuisine shot to literary prominence in the 11th and 12th centuries, after Khitan raids on the Song capital of Bianliang (汴梁) sent thousands of the city’s wealthy and well-connected fleeing to the south. Along with the Song government, these refugees eventually made their way to the new capital in the coastal city of Lin’an (临安), today’s Hangzhou.

For a time, Bianliang’s displaced elites vocally pined for their former home. Written decades after the city’s fall, Meng Yuanlao (c. 1090-1150)’s aptly-named Eastern Capital, A Dream of Splendor (《东京梦华录》) commits to text an already fading memory, recalling street by street the food culture of the old city. In its pages are named dozens of long-lost markets, restaurants and tea shops, as well as a litany of intriguing dishes, some of which are also described in cookbooks from around the same time.

“Red silk” (红丝) was a steamed pudding made from sheep, pig and chicken blood. “Jade chess pieces” (玉棋子) were small rice flour cakes fashioned like the flat pucks shapes used in the Chinese game of Go. Detectives of the era’s elegant cuisine have even brought versions of long-lost dishes like “all-fairies soup” (群仙羹) back to modern tables.

... restaurants in Lin’an were mostly operated by refugees from Bianliang and continued to serve northern tastes like mutton, braised kidneys and all sorts of thick soups, called geng 羹.

It wouldn’t be long before the refugees of Bianliang began to sing the praises of their new home, depicting Lin’an amid a commercial and social renaissance that included a new and cosmopolitan gastronomic culture. Even more than in the lost northern capital, life in Lin’an came to revolve around pleasure, glittering entertainment and dining.

According to a contemporary guide to the new capital (《都城纪胜》), restaurants in Lin’an were mostly operated by refugees from Bianliang and continued to serve northern tastes like mutton, braised kidneys and all sorts of thick soups, called geng 羹. But even those restaurants that advertised their fare as “southern food” (南食 nanshi), were in fact already a hybrid of tastes. Out of these mixed beginnings, Song dynasty Hangzhou developed its own distinct culinary fashions, blending the northern heritage of noodles and cakes with the diverse seafood and abundant produce of the south.

And with taste came rules. The unwritten codes of Lin’an’s fashionable pleasure districts included how to dress, how to drink, even how to order. Starting your meal with large dishes first meant that you were pressed for time, small dishes indicated that you wished to linger. Ridicule awaited those who displayed their ignorance by ordering their wine and food incorrectly.

Jiangnan’s dazzling culinary preeminence lasted long past the Song dynasty.

Writing ‘the land of fish and rice’

Even after China’s political centre moved back north, the combination of gentle weather, abundant crops and merchant wealth all assured Jiangnan’s continued status as a centre of sublime cuisine. Visiting Hangzhou in the late 13th century, soon after the Mongols established a regional capital in today’s Beijing, Venetian merchant Marco Polo was astounded by the abundance of the city’s many markets, laden with fruits and fresh produce, vast quantities of pepper from the Moluccas spice islands and above all an enormous supply of fish that is bought and sold each day, “so great is the number of inhabitants who are accustomed to delicate living”.

But nowhere does he mention the region’s famous love of shellfish. Perhaps he was there in the wrong season.

A prodigy at poetry and histories, he [Yuan Mei] quickly attained rank and position but left both behind to retire to his “Garden of Contentment” (随园), the name he gave to his studio near Nanjing.

Over these years, a steady stream of food writings — essays, odes, even cookbooks — attests to the growing sense of Jiangnan’s distinct gastronomic culture as a blending of cuisine, literature and beauty. The growing library of Jiangnan food writing would come to include the farmer’s treatise Madame Wu’s Handbook for Wives (《吴氏中馈录》), the medicalised cuisine of Yiya’s Legacy (《易牙遗意》) and the narrative descriptions in the Tales of Old Wulin (《武林旧事》). Above all, Jiangnan’s literary face was local. Whether travelling or dreaming of home, writers focused on food as the heart and soul of the region. Local writers praised the fresh produce and sublime preparations, nourishing the imagination if not the stomach of the reader who had yet to visit this “land of fish and rice”. The recognisable tradition of Jiangnan cuisine was as much a product of the scholar’s study as it was of the dining table.

Yuan Mei, the unparalleled epicure

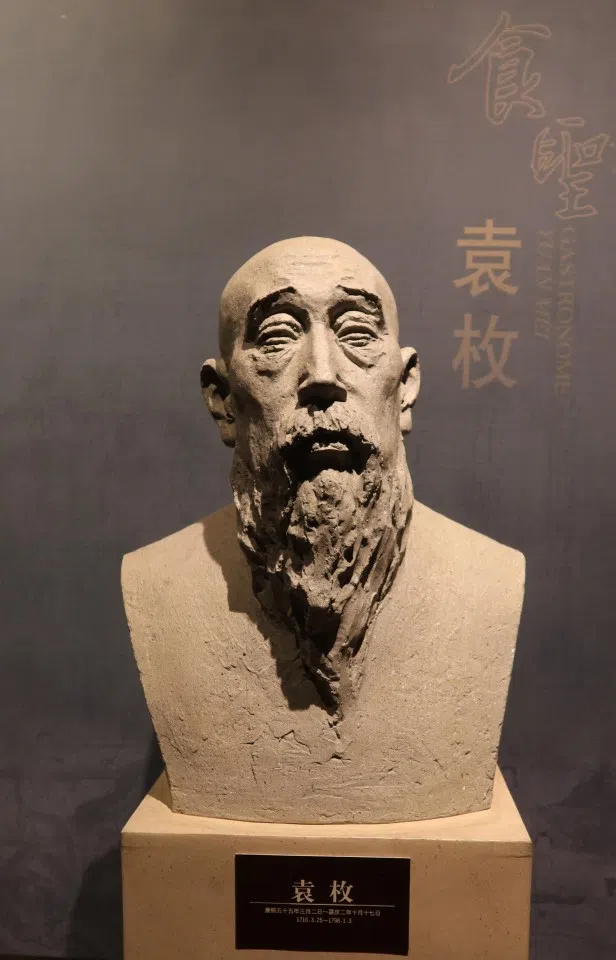

But of all the region’s literati epicures, none could approach the great gourmand Yuan Mei 袁枚 (1716–1797).

Born into relative poverty and raised by an aunt, Yuan quickly developed a love of books — the first of his many voracious appetites. A prodigy at poetry and histories, he quickly attained rank and position but left both behind to retire to his “Garden of Contentment” (随园), the name he gave to his studio near Nanjing. Yuan also gave this name to a collection of poetic criticism and perhaps most famously, to a book of recipes.

Yuan Mei’s Recipes from the Garden of Contentment (《随园食单》) was a collection of Jiangnan dishes but it was much more. The recipes themselves were among Yuan’s favourites, but they were hardly his own creations. Most were cribbed from other food writing of the time, including more technical works such as Flavouring of the Pot (《调鼎集》), a thick collection of shorthand reference notes on hundreds of dishes.

But Yuan was not writing for the cook; his audience was the cultured gourmand. He begins his treatise by unloading a personal list of rules and grievances — the latter including food that is visually unappealing or overcooked, or drunken diners that ruin a fine meal. Each rule is buttressed with Confucian quotes and literary metaphors. No longer simply a matter of personal pleasure, dining becomes a metaphor of knowledge and path to virtue.

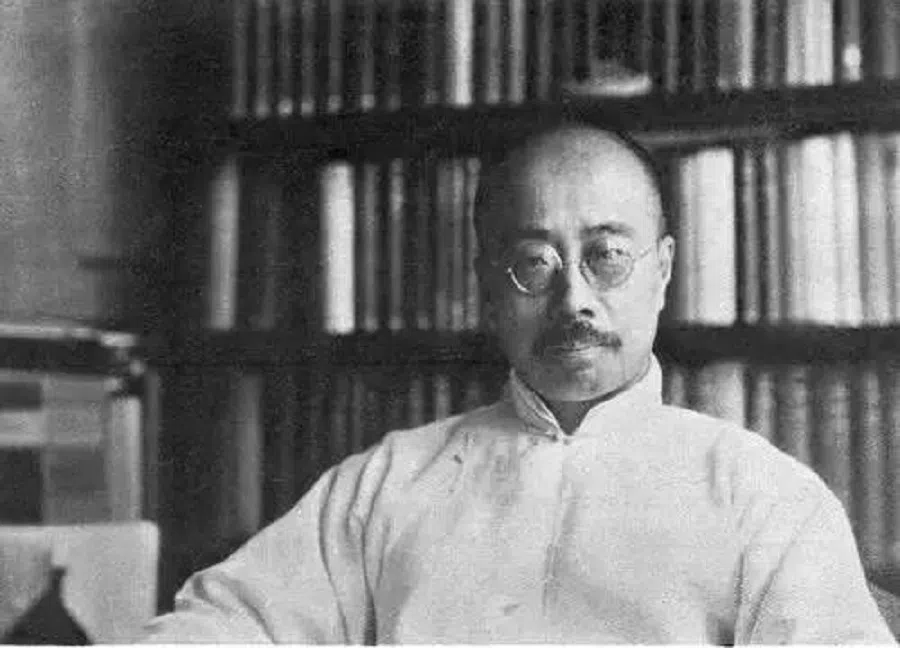

Yuan was far from the last of Jiangnan’s culinary voices. Shaoxing native Zhou Zuoren (周作人 1885-1967) wrote extensively about food, penning dozens of short pieces musing about topics from chestnuts to cannibalism.

Returning to the food itself, Yuan displays the culinary aesthetic of a well-heeled literatus but never strays far from his native land. Praise for a dish’s taste is often paired with a locally-sourced cultural tidbit — a moniker or saying, the location of the best produce, or an association with a famous figure. With these, Yuan roots the culture of sublime cuisine firmly in the soil of home.

Yuan was far from the last of Jiangnan’s culinary voices. Shaoxing native Zhou Zuoren (周作人 1885-1967) wrote extensively about food, penning dozens of short pieces musing about topics from chestnuts to cannibalism. While Zhou was culinarily won over by Beijing, his better-known brother, essayist Lu Xun 鲁迅 (1881-1936) remained rooted in the tastes of home, using details like one protagonist’s famous love of anise-spiced beans (茴香豆), to add local flavour to his stories.

And the best may be yet to come. Culinary fashion and literary styles constantly renew themselves. Jiangnan’s newest age of gastronomes may just now be finding its voice on social media.