[Photos] When snakes love humans: The White Snake story and its roots in Zhenjiang

Tracing the roots of the legendary White Snake love story to Zhenjiang’s Jinshan Temple, writer Ng Kong Ling journeys through myth and history to uncover how ancient tales of snakes entwined with human passion reveal unexpected heroes — and why fascination with these enigmatic creatures endures today.

(Photos by Ng Kong Ling unless otherwise stated.)

This being the Year of the Snake, one would naturally talk about the animal in question, and the first thing that comes to mind is the Legend of the White Snake. The story is often associated with West Lake in Hangzhou, but it was not until a recent visit to Zhenjiang, Jiangsu, that I discovered the legend has deep roots there as well.

In fact, the Legend of the White Snake made it to China’s first list of national intangible cultural heritage items in 2006, and the application was submitted by Zhenjiang, which is officially recognised as the place where the tale first originated.

Pursuit of love, happiness and freedom

As one of China’s four major folktales — along with the Butterfly Lovers, Lady Meng Jiang, and the Weaver and the Cowherd — Legend of the White Snake tells of a white snake spirit who, after a thousand years of cultivation, transforms into a woman named Bai Suzhen, or Lady Bai. Accompanied by the green snake spirit Xiaoqing, Lady Bai arrives at West Lake and falls in love with a pharmacy assistant named Xu Xian. They get married and run the Baohe Hall (保和堂) pharmacy in Zhenjiang.

However, the abbot of Jinshan Temple, Fahai, discovers Lady Bai’s true identity. During the Dragon Boat Festival, he tricks her into drinking realgar wine, forcing her to reveal her original form, then deceives Xu Xian into coming to Jinshan Temple (金山寺).

To rescue him, Lady Bai and Xiaoqing battle Fahai, leading to the famous flooding of the temple, but Fahai manages to subdue Lady Bai beneath Leifeng Pagoda. After years of cultivation, Xiaoqing finally topples the pagoda, defeats Fahai (who ends up inside a crab’s belly), and rescues Lady Bai, bringing the story to a happy ending.

The snake was an important totem and symbol for the people of Chu, and locals in the area have an ancient tradition of snake worship.

The story began with folk rumours, totems and beliefs about snakes — tales of snakes devouring people, snake spirits bewitching humans, and love between snakes and humans. Over time, it evolved into a full narrative about pursuing love and fighting for happiness and freedom.

Legend of the White Snake originated over the Tang dynasty and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, and took on its basic form by the Southern Song dynasty. By the Yuan dynasty, it had been adapted by the literati into zaju (杂剧, a form of musical comedy) and huaben (话本, storytelling scripts). The earliest complete version in circulation today is “Lady Bai subdued under Leifeng Pagoda for eternity” (《白娘子永镇雷锋塔》), included in Warnings to the World (《警世通言》, Jingshi Tongyan), a Ming dynasty anthology compiled by historian and novelist Feng Menglong.

The tale has been widely circulated over the centuries. Even today, it is still adapted into novels, films and other forms of literary and performing arts. It has become known in every household, with Zhenjiang and Hangzhou as two of the most important places where the legend has been preserved and passed down.

Fictional tale, real locations

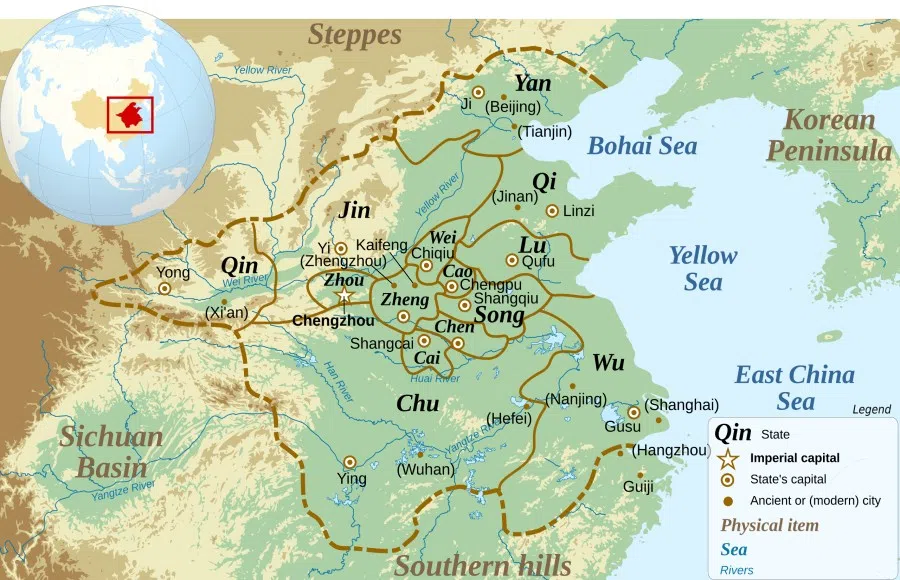

Zhenjiang is located at the former border between the states of Wu and Chu during the Spring and Autumn Period. The snake was an important totem and symbol for the people of Chu, and locals in the area have an ancient tradition of snake worship. From the early Tang dynasty, there was a nascent legend in Zhenjiang about a monk from Jinshan Temple subduing a white snake.

Many of the key locations featured in Legend of the White Snake, such as Jinshan Temple, Baohe Hall, White Dragon Cave and Fahai Cave, are real sites in Zhenjiang today. During the Dragon Boat Festival, theatres in Zhenjiang often stage performances based on the White Snake legend, and it is a custom to drink realgar wine and visit Jinshan Temple.

Baohe Hall is located on Wutiaojie (五条街, lit. Five Streets) in Zhenjiang. Feng Menglong’s Ming dynasty tale says that when Xu Xian first arrived in Zhenjiang, he worked at the pharmacy by day, and lodged at Wanggong Building (王公楼) in Wutiaoxiang (五条巷, lit. Five Lanes) at night, referring to what is now Wutiaojie.

While the story is fictional, the locations are real, as was Fahai. In the legend set in the Shaoxing era during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of the Southern Song dynasty, Fahai is the antagonist. However, the real Fahai was a respected Tang dynasty monk.

Wutiaojie is a lively and bustling commercial area in Zhenjiang, not far from Jinshan Temple. In Legend of the White Snake, Xu Xian and Lady Bai work at Baohe Hall, dispensing medicine and aiding the poor, and curing many difficult illnesses. With fewer people falling ill, there was a drop in numbers who prayed for healing at Jinshan Temple; this lack of piety displeased the monk Fahai, setting in motion the ensuing conflict.

While the story is fictional, the locations are real, as was Fahai. In the legend set in the Shaoxing era during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of the Southern Song dynasty, Fahai is the antagonist. However, the real Fahai was a respected Tang dynasty monk. Born into a prominent family as Pei Wende, he became a monk and took the religious name Fahai.

While meditating on Mount Jin, Fahai saw that the temple buildings were dilapidated and overgrown with weeds, and pledged to restore the temple. During the reconstruction, a large cache of gold was unearthed while laying the foundation, and Fahai turned all the gold over to the state. Moved by his actions, the emperor bestowed the gold to the temple for its rebuilding. The temple came to be known as Jinshan Temple, and Master Fahai is regarded as one of its founding figures.

The Jinshan Temple seen today is the result of generations of repair and reconstruction. The main buildings of the temple are constructed with the mountain, such that they are integrated as one. Looking up from the foot of the mountain to the summit, the halls, balconies and pavilions are closely connected in a dense architectural cluster, hence the saying: “One sees the temple and the pagoda, but not the mountain.”

Fahai came to Jinshan and found the cave to meditate, and burned part of his finger as a pledge to restore the temple. When completed, it was named Jinshan Temple, and Fahai disappeared.

Halfway up the mountain is Fahai Cave, where Fahai meditated and cultivated himself. The cave is small; just a few people in it makes it hard to move around. Within is a statue of Fahai, smiling and benevolent, unlike the antagonist in the Legend of the White Snake.

According to the information at the cave entrance, Fahai came to Jinshan and found the cave to meditate, and burned part of his finger as a pledge to restore the temple. When completed, it was named Jinshan Temple, and Fahai disappeared.

Just for fun, let’s compare this with the story and imagine: if Fahai lived in this cave, meditating and restoring the temple, would he be bothered to go to the marketplace and stir discord? And after the temple was completed, he vanished — did he really hide inside a crab’s shell, never daring to show himself again?

At its peak, this huge temple housed more than 3,000 monks; through thousands of years, it has been a place full of legendary flavour.

Behind the legend: Who’s the hero?

Jinshan Temple is a well-known Zen Buddhist monastery in China. Since its founding, Jinshan Temple has had its fair share of snake legends. It is the place of origin of the grand ritual Shuilu Fahui (水陆法会, lit. water and land dharma assembly), which began with Emperor Wu of Liang during the Northern and Southern dynasties period over 1,500 years ago.

The emperor dreamed that his beloved wife Chi Hui, or Lady Xi — who had just passed away — was transformed into a venomous snake and asked the emperor to perform Buddhist rites to help her soul find peace. Thus began the Shuilu Fahui, which gradually became the biggest sacred ritual of the time, making Jinshan Temple the hall where it began. Today, the ritual is listed among China’s intangible cultural heritage, and has spread to other parts of the world.

During the Qing dynasty, Jinshan Temple was ranked among China’s four great temples, alongside Putuo Temple, Wenshu Temple and Daming Temple. At its peak, this huge temple housed more than 3,000 monks; through thousands of years, it has been a place full of legendary flavour.

Many legendary stories are set in and around Jinshan Temple. Besides the flooding scene in the Legend of the White Snake, other stories include outlaw Zhang Shun’s night raid of the temple in Water Margin, and female general Liang Hongyu beating the war drums in the battle for Mount Jin. In Journey to the West, the monk Tang Sanzang takes his monastic vows and grows up at Jinshan Temple, where he is put forward to preside over the Shuilu Fahui for the Tang Emperor, and where he begins his journey to the Western Regions to retrieve the Buddhist scriptures.

These legends and tales are based on historical fact, with fictional elements thrown in. But even in made-up tales, there are traces of the original subjects, which are embellished and exaggerated over time to make it engaging.

In real life, of course, a magical duel involving the flooding of Jinshan Temple could never happen. However, in ancient times, Mount Jin was indeed an island in the middle of the Yangtze River — it only gradually connected with the surrounding land during the Qing dynasty. So, in Lady Bai’s time, it would have been easy to stir up winds and waves around Jinshan Temple.

The fight between human and snake was also real. There are historical records of Master Fahai losing an arm while subduing a “dragon” (referring to a snake).

One needs to exaggerate a little when writing a story — the epic scene of summoning torrential waters from West Lake and getting help from the Dragon Kings of the Four Seas along with their marine minions is a key plot point in the Legend of the White Snake, and leaves quite an impression.

On the very top of Mount Jin stands the iconic Cishou Pagoda, first built during the Southern Qi and Liang dynasties (two of the Southern dynasties), which explains why Fahai and Lady Bai’s battle involves a pagoda. But in crafting the story, the narrative scope had to be expanded, and so Leifeng Pagoda in Hangzhou was used instead.

The fight between human and snake was also real. There are historical records of Master Fahai losing an arm while subduing a “dragon” (referring to a snake). While Fahai was restoring the old monastery, a large white python often appeared on the mountain path, biting and injuring passersby, deterring people from going up the mountain to pray and offer incense. Fahai stepped up to rid the people of the scourge and had his right arm bitten off while subduing the python; in the end he drove it into the river, removing the threat.

North of Mount Jin is White Dragon Cave. According to Stories of Divine Monks (《神僧传》) from the Ming dynasty, in the cave was a white python that breathed out toxic smoke, deadly to anyone who passed. The Tang dynasty monk Lingtan went into the cave to meditate, and the python fled into the sea — a similar story to Fahai’s.

Of course, the story got bigger as it spread. It is rumoured that White Dragon Cave connects directly to West Lake, and this claim is carved in large characters at the cave; it is said that Xu Xian secretly travelled through here to Hangzhou, to meet Lady Bai at the Broken Bridge on West Lake.

Within the Jinshan Scenic Area is the Jinshan Cultural Expo Park (金山文化博览园), showcasing Mount Jin’s history and culture in its replica traditional-style buildings. Among the exhibits, the biggest draw is a live white snake.

Giant snakes on the prowl

Since ancient times, there have been giant snakes in Mount Jin, shaping various folk legends about snakes. It would not be unheard of to have snakes and bugs on a river island scurrying into the temple. And since Buddhist monks have a precept of not taking a life, it would make sense for them to drive the pythons into the sea.

Given its long history as a prominent Buddhist temple, people talked especially about the strange and wondrous tales spread about Jinshan Temple, which got increasingly wonderful with each retelling as folk artists kept adding to it.

Even after more than a thousand years, there have been recent sightings of giant snakes at Jinshan Temple. Within the Jinshan Scenic Area is the Jinshan Cultural Expo Park (金山文化博览园), showcasing Mount Jin’s history and culture in its replica traditional-style buildings. Among the exhibits, the biggest draw is a live white snake.

A worshipper found it in the mountain a few years ago; it was captured by the staff and put on display in the exhibition hall. This giant snake measuring over one metre long has been dubbed Lady Bai, drawing visitors for photographs.

When I went, the white snake had just shed its skin. A strip of the old skin hung from the display case, while the snake itself lay curled in a dim corner, barely visible, prompting visitors to murmur and fret. But the venue was prepared. Above the display case hung a sign written large: “Self-cultivation is not easy — please do not disturb.”

One may wait a thousand years for just one encounter; if you are fated to meet, it will happen.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “蛇影千年 中国镇江寻访《白蛇传》”.

![[Big read] Prayers and packed bags: How China’s youth are navigating a jobless future](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/16c6d4d5346edf02a0455054f2f7c9bf5e238af6a1cc83d5c052e875fe301fc7)