Why civilisations burn their own books

In times of peace, books are indeed a treasure trove. However, the scholarly air that emanates from tireless reading and burning the midnight oil holds little value amid the blood and chaos of years of war, remarks Hua Language Centre director Chew Wee Kai.

When I was a kid, we often recited a doggerel verse in Chinese: “Cursed Qin Shi Huang, he burned books but didn’t get them all, now I’m studying in misery.”

Many people would feel that books are the cause of their suffering. Over time, the old stories of Eastern Han dynasty scholar Sun Jing tying his hair to a beam, and Warring States period statesman Su Qin pricking his thigh with an awl (both to stay awake while studying), or Western Han dynasty scholar Kuang Heng boring a hole in the wall to “steal” light from his neighbour to read, are no longer chicken soup for the soul.

Meanwhile, the old adage about the midnight hours or dawn being the best time for a young man to study has gradually become a faraway legend.

When the inhumane demons of war are blinded by bloodlust, and unarmed commoners count it a luxury just to be alive, they can hardly think about how books cultivate character.

From nourishing the soul to filling the bellies

Things can have vastly different fates, depending on when and where they exist. The destiny of books is a slave to the times amid the vicissitudes of their function and value.

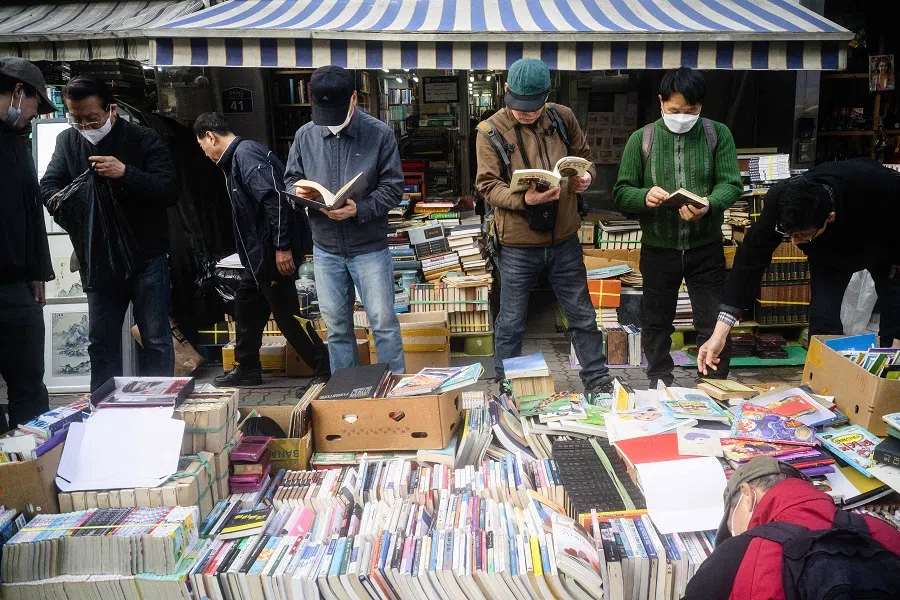

In times of peace, books are indeed a treasure trove — “if a man wishes to fulfill his lifelong ambitions, he must diligently study the Five Classics.” Books essentially became a secret manual to success and honour, like the martial arts manual Sunflower Scripture (葵花宝典) in Jin Yong’s wuxia novel The Smiling, Proud Wanderer.

Books have always held an esteemed position in society. However, the scholarly air that emanates from tireless reading and burning the midnight oil holds little value amid the blood and chaos of years of war. When the inhumane demons of war are blinded by bloodlust, and unarmed commoners count it a luxury just to be alive, they can hardly think about how books cultivate character.

A few weeks ago, I read in the morning news that Israel threatened to annex Gaza if Hamas did not swiftly release hostages. Alongside was a striking photo of children placing heavy books in a box amid the rubble of bombing. The caption said matter-of-factly that the resurgence of conflict had worsened the lack of resources in the Gaza strip, and displaced children were scavenging books from a bombed Islamic university to use as fuel for cooking.

Using books as fuel signals that the environment no longer allows people to cherish spiritual nourishment. When life gets tough, no one cares that the pages being torn out are the authors’ painstaking work. In a land scarred by bombing, books sacrifice themselves with their final glow to warm the bellies of refugees fighting for survival.

Ah, books — multipurpose “blocks” that shed the nobility of being food for the soul, destroyed to quell hunger, bearing out the words of Chinese cartoonist Huang Miaozi: “The greatest practical value of books is that, when it’s freezing cold, their pages can be torn out one by one and burned in a stove for warmth.”

In China, burning books was never exclusive to Emperor Qin Shi Huang. The bamboo volumes he did not burn subsequently fell to Xiang Yu, the warlord of Western Chu, who later conquered the Qin capital Xianyang and completed the first emperor’s unfulfilled vision of literary annihilation.

Burning of books throughout history

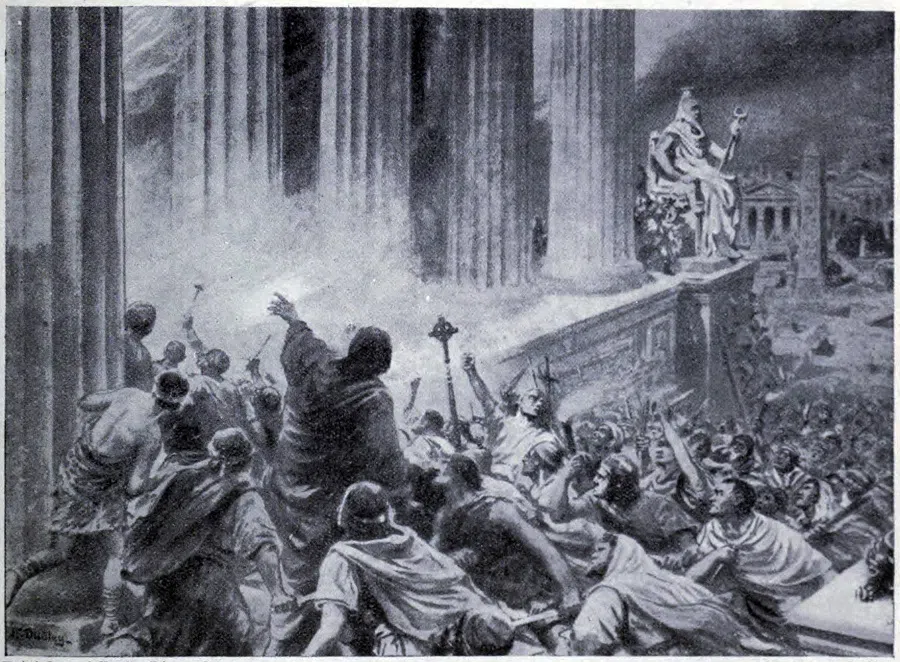

Throughout history around the world, it is mostly in times of chaos that books suffer. There are plenty of historical records of books being banned and destroyed; the West may actually have a slightly longer history of burning books than China.

About three millennia ago, after conquering the Assyrian capital, the Babylonians torched the royal library, marking the world’s first large-scale destruction of books. In ancient Rome, Julius Caesar also left an unsavoury mark as one who burned books — his actions reduced to ashes what was once the world’s largest library, the Library of Alexandria, resulting in half a million manuscripts including countless volumes documenting Greek civilisation being lost overnight. In the 13th century, France burned the Talmud, a Jewish religious text; countries such as the Czech Republic, Spain, Russia, and Italy have all destroyed tens of thousands of books under various pretexts.

In China, burning books was never exclusive to Emperor Qin Shi Huang. The bamboo volumes he did not burn subsequently fell to Xiang Yu, the warlord of Western Chu, who later conquered the Qin capital Xianyang and completed the first emperor’s unfulfilled vision of literary annihilation. Chinese emperors continued to burn books over the next 2,000 years.

For example, after the Yuan Emperor of the Liang dynasty (one of the four Southern dynasties during the Northern and Southern dynasties period) was defeated by Western Wei, he lashed out at his books: “After reading ten thousand volumes, this is my reward!”

With one order, he consigned his 140,000-volume collection to the flames.

Li Yu, the last ruler of the Southern Tang dynasty, loved books and the arts, and had an enormous palace library. When the Song army reached Nanjing, he instructed: if the city fell, the librarians were to burn all his beloved books rather than let them be scattered around.

Even the culture-loving Emperor Qianlong of the Qing dynasty issued dozens of orders to destroy books over his 60-year reign, 150,000–700,000 volumes were confiscated or lost, topping the list for literary destruction over the dynasties. And 93 years ago, when the Japanese Imperial Army invaded Shanghai, they bombed the well-established Commercial Press and set fire to the Oriental Library and the 460,000 books in it.

Forbidden literary works that could cost one’s life

For a long time, in respectable society, erotic literature rarely saw the light of day. Obscene works that could seemingly corrupt morality were prohibited and destroyed. As a result, stories of forbidden love affairs, same-sex romances and erotic encounters went underground.

If one was lucky enough to get their hands on a volume, curling up under a blanket on a snowy night to read a forbidden book felt like puffing on opium, the words sending one into dreams and illusion.

Among the erotic classics of old, the well-known The Plum in the Golden Vase (Jin Ping Mei 《金瓶梅》) and The Carnal Prayer Mat (Rouputuan 《肉蒲团》) were just the tip of the iceberg — there were many lesser-known, sensual tales of passion. The Ming and Qing dynasties were peak periods for such literature; a quick Google search will turn up racy titles such as Wushan Erotic Chronicles (《巫山艳史》), The Vinegar Gourd (《醋葫芦》) and The Embroidered Couch (《绣榻野史》).

In an environment where thought was tightly controlled, scholars trembled at the thought of literary persecution. A slip because of books could land one in trouble, leading to the extermination of one’s family, and the implication of an entire clan. Qing dynasty scholar Gong Zizhen lamented: “I shy away in fear of literary inquisitions.”

Then there was Qing dynasty poet Xu Jun, who wrote an untitled poem with these lines, meant as a lighthearted joke: The clear breeze knows no words/Why does it ruffle the pages? (清风不识字,何故乱翻书?) The simple word “qing” (清, meaning pure or clear, also refers to the Qing dynasty), was taken to be a slight against the Manchus, which led to Emperor Yongzheng ordering Xu’s execution.

Sacrificing culture for survival

Before printing became widespread, large-scale book-burning operations led by the authorities amounted to cultural catastrophes. The destruction of books — whether by fire or by prohibition — are often linked to politics, because books have an invisible penetrative power of dissemination, and those in power wanted to control ideas and eliminate dissent, leading them to such misguided actions.

... in this wide world of ours, war is forcing people to burn pages of books as fuel for fire to cook their meals.

In times of upheaval, books were not lucky items — they could not be taken lightly, and destroying them was the best strategy. Ironically, censorship only whetted the public’s appetite for reading. Curious readers and profit-chasing bookstores provided a space for banned books. If one was lucky enough to get their hands on a volume, curling up under a blanket on a snowy night to read a forbidden book felt like puffing on opium, the words sending one into dreams and illusion.

The idiom “cooking words to stave off hunger” alludes to writing on yellowed paper by a lone light just to earn a living, reflecting a certain spiritual desolation. But today, in this wide world of ours, war is forcing people to burn pages of books as fuel for fire to cook their meals.

Is this not the helplessness of “cooking cranes and burning zithers” — a sacrifice of beauty and culture for mere survival?

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “焚书疗饥”.