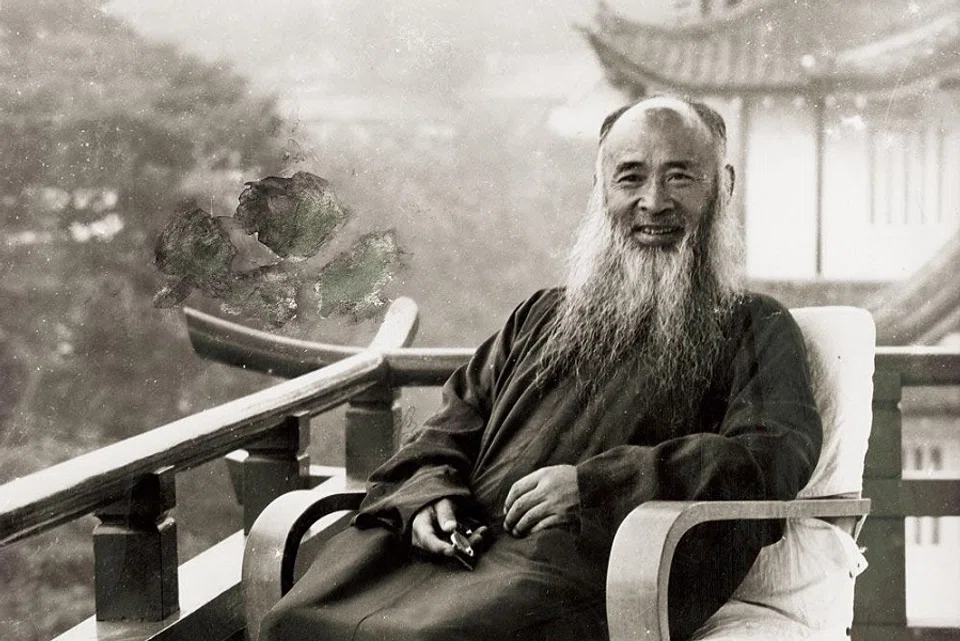

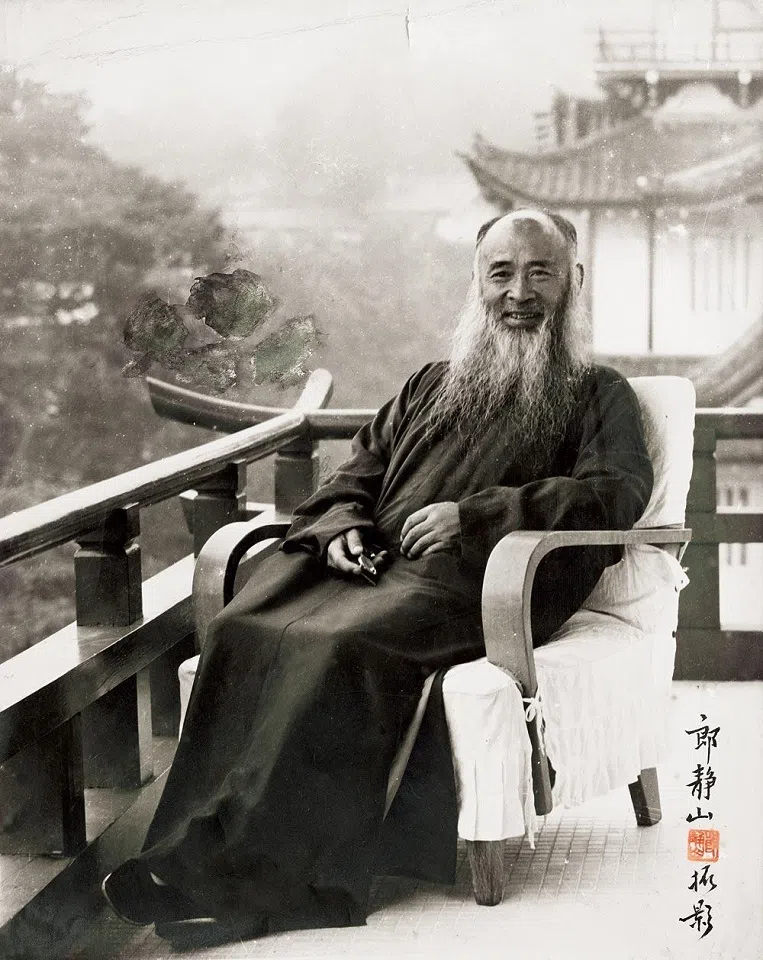

Zhang Daqian, painter and gourmet

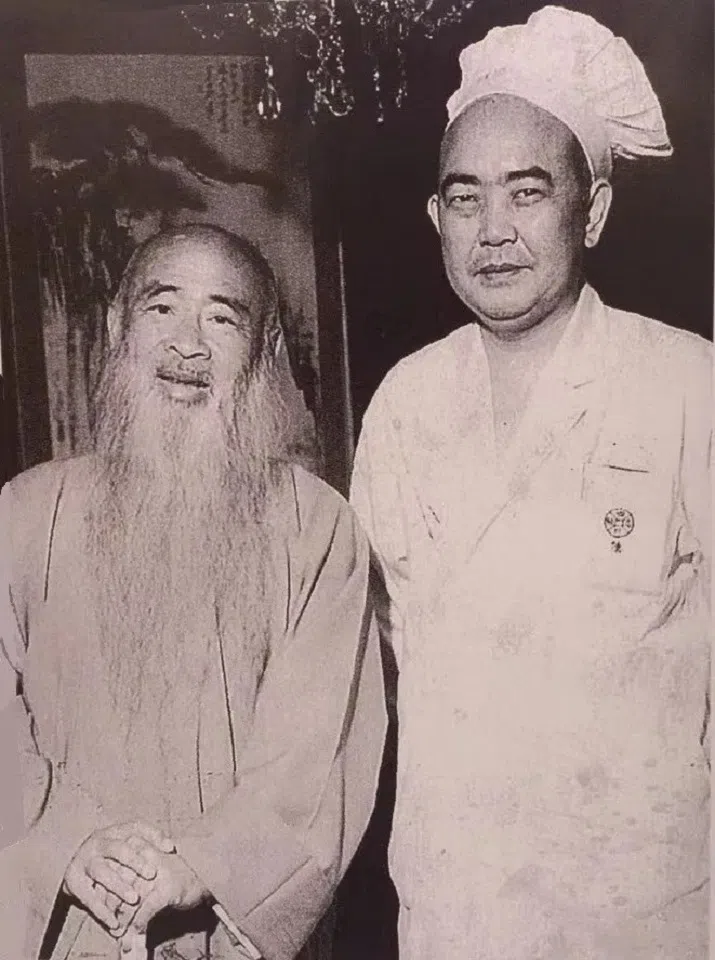

Writer Shen Jialu shares the culinary side of renowned Chinese painter Zhang Daqian. As a gracious host willing to incorporate ingredients and cooking techniques from different regions, Zhang’s culinary skills are just as prominent as his painting skills.

Zhang Daqian (Chang Dai-chien) was a world-renowned painter, and a gourmet who appreciated the culinary arts. He even said, “Artistically speaking, I am better at cooking than painting.”

He lived by “making life art and making art life”, and saw cooking as artistic creation. However, his claim of being better at cooking than painting should not be taken literally. Throughout Zhang’s artistic life, cooking and painting resonated simultaneously as a harmonious duet.

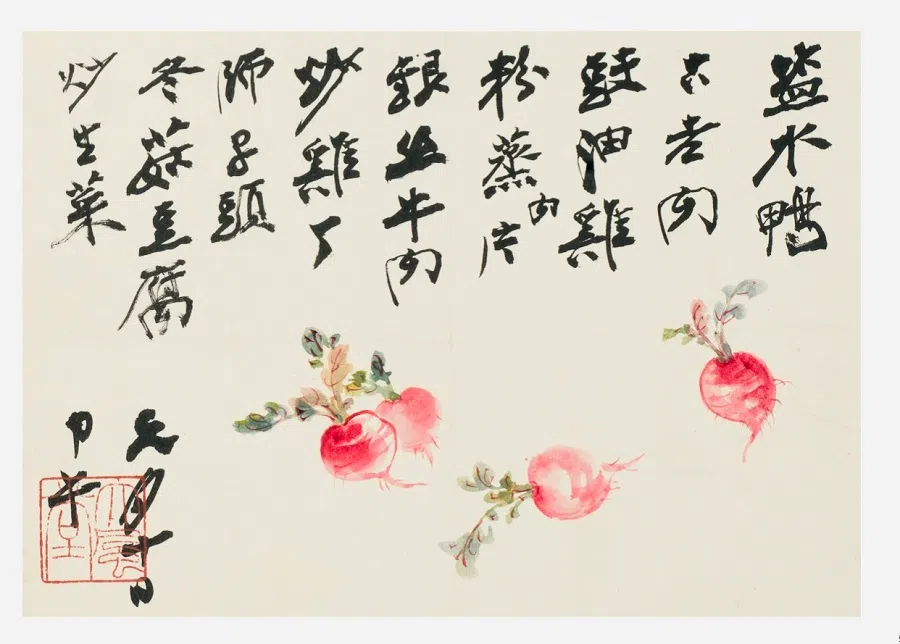

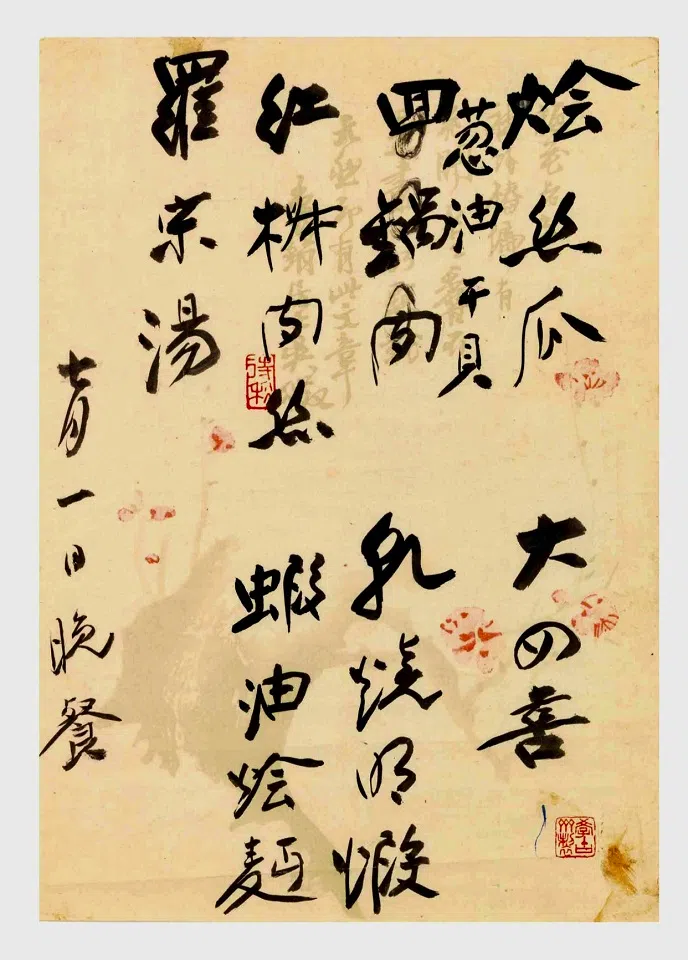

There are certain words often used in articles to describe Zhang’s artistic life, and I am particularly interested in the term “cuisine”. My eyes would light up whenever I come across Zhang’s handwritten menus at auction previews. I would admire them, take photos and verify their authenticity.

One day, a friend showed me a batch of Zhang’s menus, more than 50 pages of duplicates and originals. I eagerly studied the more than half that I had never seen before. Even in the sweltering summer, I felt refreshed, as if there was a breeze under my arms as I guzzled seven cups of drinks.

Zhang loved meat and had it at almost every meal. Rich dishes such as braised pork, sugar-glazed pork knuckle and Dongpo pork were his favourites...

Entertaining guests with good food and hot drinks

Since the Ming and Qing dynasties, poets often drifted with the wind, drowning their sorrows in wine and expressing their aspirations in poetry. Over the past 200 years, there have been plenty of painters such as Xu Wei, Ren Bonian, Wu Changshuo and Xu Beihong, who were at one time stuck and struggling. However, with the development of the commodity economy, talented artists such as Zhang Daqian could thrive in the market by selling their crafts, living a life of luxury, surrounded by fine clothes and exquisite cuisine.

Cao Pi — the first emperor of Wei during the Three Kingdoms period — said, “It takes three generations to understand clothes, and five to understand food.”

According to biographies of Zhang, his mother was a good cook. Every meal was carefully prepared, and the fragrance of mala (numbing and spicy) became the basic flavour for the family.

Zhang loved meat and had it at almost every meal. Rich dishes such as braised pork, sugar-glazed pork knuckle and Dongpo pork were his favourites, while Jinhua ham and scallion-braised sea cucumber were the magic weapons to whet his appetite.

I also have reason to believe that Zhang would explore local cuisine and customs in his travels across China, using banquets or cooking as an excuse. Clad in his blue robe, with his flowing beard, he would venture into streets and alleys, visit markets, and chat with farmers and vendors, committing to memory these “foreign” flavours and ingredients to incorporate into his cooking later.

Zhang was a man of passion, warm and hospitable, with high emotional intelligence and exceptional social skills. As the value of his paintings skyrocketed, he would often welcome guests with open arms, heating wine and tea, spending just as much as he earned.

Coupled with his wealth of bizarre and fascinating stories, he would have a huge gathering when the humour took him, and talk freely and endlessly, creating an optimistic and uplifting atmosphere that drew like-minded friends to his side.

In Beiping (now Beijing), Zhang was particularly close to fellow artists such as Yu Fei’an. They would frequently dine together at the renowned Chunhua Restaurant (春华楼), known for its master chefs and signature dishes.

Later, they established the “Rotary Club” (转转会), comprising 12 members: Zhang Daqian, Pu Xinyu (Puru), Zhou Zhaoxiang, Qi Baishi, Chen Banding, Yu Biyun, Chen Baochen, Yu Fei’an, Pu Xuezhai (Pu Jin), Fu Zengxiang, Xu Nailin and Cheng Duolu.

The Rotary Club was like an art salon, where members would bond while composing poetry, painting and exchanging artistic ideas in a casual atmosphere. Such dinner gatherings were a fashionable trend among the literati in the Republic of China.

“His sour and spicy fish soup was fragrant and extremely fresh, making one’s mouth water. Truly unforgettable.” — Fellow artist Xie Zhiliu

In 1936, Xu Beihong wrote in the preface to a book of collected paintings by Zhang Daqian: “He excels at Sichuan cuisine, enthusiastically engaging in high-spirited conversations, often in the kitchen cooking exquisite dishes for his guests. People would forget their worries as the gathering runs through the night into the next morning.”

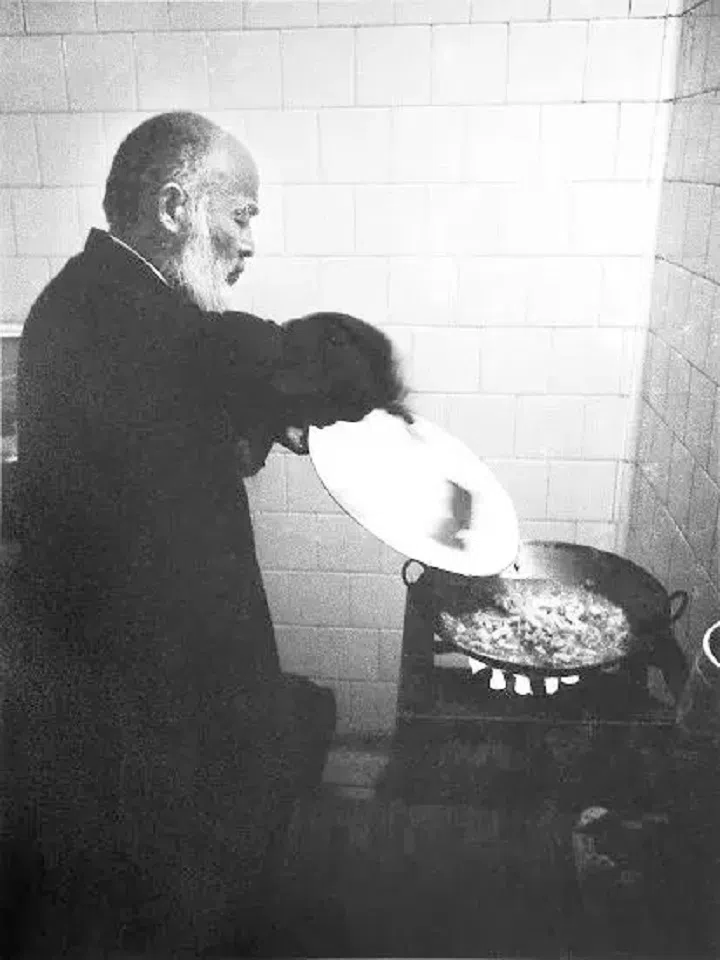

Painter Xie Zhiliu also recalled in his writings: “Daqian’s side talent was being a good cook. He was also warm towards guests, personally cooking in the kitchen for them. His sour and spicy fish soup was fragrant and extremely fresh, making one’s mouth water. Truly unforgettable.”

Rolling up his sleeves to cook

Hosting a banquet in one’s own home is showing the highest courtesy to guests. Most literati would have household servants or hired chefs to prepare meals — Lu Xun had invited restaurant chefs to cook in his home. However, Zhang Daqian liked to roll up his sleeves to cook. He treated his home-cooked dishes as art, inviting guests to savour them. His kitchen became a platform for culinary experimentation, and he showed his genuine sincerity through hometown flavours.

According to Chinese etiquette, the host of a banquet would personally plan the menu, and so Zhang’s menus also reflected traditional Chinese culture.

Fellow literati recalled that when old friends and honoured guests visited, or on important occasions, Zhang would carefully plan the menu; write down guests’ names as a sign of respect; indicate who cooked each dish, such as “Qian” (himself), “Wen” (his wife Xu Wenbo), “Ke” (his daughter-in-law), or “Liu Gu” (六姑, lit. Sixth Aunt, referring to his chef at Bade Garden in Brazil); specify ingredients in the dishes; add concise tips for chefs as a special consideration, such as “scallion segments eight centimetres long”, “thoroughly deshell shrimp”, or “add scallion threads to taste when serving”; and inscribe and stamp important banquet menus for guests to take home as a keepsake.

After relocating overseas in 1949, despite being in a foreign land and unable to cook extravagant dishes, Zhang Daqian could still masterfully blend flavours. He happily accepted and perfectly replicated various cuisines, including Cantonese, Shandong, Anhui and Jiangsu dishes.

In 2001, a Taiwanese man surnamed Fu auctioned off a book Daqian’s Home Culinary Study (《大千居士学厨》) for charity. The book was a collection of notes recording Zhang’s daily meals and banquet menus during his stay at the home of politician Guo Youshou in Paris in 1962. This casual, scribbled journal of just about 800 words was brimming with Zhang’s personality.

The journal’s value lay in its inclusion of 17 dishes cooked by Zhang, describing ingredients and cooking methods, some in detail, others simply. These recipes were not too complex in terms of cooking method and equipment, allowing anyone to showcase their culinary skills anytime, anywhere.

After leaving France, Zhang went to Belgium, and stayed with a friend surnamed Fu. Zhang gifted this notebook to Fu as a keepsake. It eventually fetched a good price at auction, causing a stir and becoming a charming anecdote.

Three characteristics of Zhang Daqian’s menus

After carefully reading these menus from friends, I discovered three distinct features of Zhang Daqian’s menus.

A myriad of flavours

Zhang based his food on Sichuan flavours, but no matter the setting, his menus typically featured only two or three mala dishes, such as Daqian-style chicken, mapo tofu, stir-fried chicken diced with chilli, bang bang chicken (Sichuan-style chicken), steamed pork with chilli, fried prawns with garlic, stir-fried chicken wings with chilli peppers, and Sichuan-style braised pork trotters with peppercorns.

The other dishes were relatively mild, such as steamed duck with wine, Chengdu-style vegetarian stew, tofu and meatballs, silver-thread beef (beef with deep-fried crispy rice noodles), Wuyuli Lake fish, duck with shredded ginger, thick chicken broth, stir-fried fresh mushrooms, scallion-roasted duck, steamed fish, and braised tofu with mushrooms.

Wandering the world, looking back at one’s hometown, never forgetting one’s initial intentions, and finding nostalgia in local flavours — this is one of the precious aspects of a Daqian-style home banquet.

Zhang often said that Sichuan cuisine is not all spicy, and that officials and upper- and middle-class households served few spicy dishes for guests, but mostly showcase the freshness of ingredients through their pure natural flavours. Some famous Sichuan chefs had also told me that clear and fresh flavours are served at grand banquets, while mala dishes are served at casual gatherings. This is the Sichuan way.

Wandering the world, looking back at one’s hometown, never forgetting one’s initial intentions, and finding nostalgia in local flavours — this is one of the precious aspects of a Daqian-style home banquet.

In Zhang’s vast culinary repertoire, we often see dishes from other regions, such as steamed duck in salt water, eight-treasure duck, sweet and sour pork, shredded meat in Beijing sauce, braised ham in honey sauce, stir-fried pork kidneys, sea cucumber braised with scallions, duck steamed with wine and orange peel, sweet and sour cabbage, borscht, braised chicken gizzards, braised pork belly, braised gluten, yellow croaker with noodles, water shield soup, and fish noodles.

Why did Zhang introduce dishes from other regions into his family banquets? Actually, it is not surprising. Perhaps during his travels and sojourns in foreign lands, Zhang, with his broad vision, would naturally draw inspiration from his surroundings. He used cooking to explore the qualities of local ingredients and often adopted techniques from other regional cuisines to create Sichuan dishes or incorporate local flavours, challenging himself in the process. Or perhaps his guests were not from Sichuan, and he needed to accommodate their dining habits.

For instance, sea cucumber braised with scallions is a specialty of Shandong cuisine, which is also the base for shredded meat in Beijing sauce. Stir-fried pork kidneys, braised ham in honey sauce, and chicken and rice with pine nuts are representative dishes of Huaiyang cuisine.

Many people do not know what xunyingtao (熏樱桃, lit. smoked cherry) is on Zhang Daqian’s menu. I learned from Chinese culinary master Xu Hefeng that it is actually smoked frog legs...

Thick chicken broth is a famous local dish from Lianshui in Jiangsu province, and Sichuan chefs adapted it into thick liver broth. Meat with pine nuts, braised chicken gizzards and shrimp oil noodle soup are quintessential Suzhou dishes.

Kung pao squid or kung pao chicken is not unique to Sichuan; the kung pao flavour originated in Guizhou and only later became part of Sichuan cuisine. Stir-fried shrimp balls, paper-wrapped chicken, abalone in oyster sauce, tofu in oyster sauce, and chicken in scallion oil are Cantonese dishes. The dish called watermelon bowl is found in Guangdong, Fujian and Jiangsu cuisine, but not in Sichuan cuisine.

Xiaolongbao and borscht became well-known in Shanghai. As for broccoli in milky soup, it is essentially cream of broccoli soup found in Chinese-style Western meals.

Many people do not know what xunyingtao (熏樱桃, lit. smoked cherry) is on Zhang Daqian’s menu. I learned from Chinese culinary master Xu Hefeng that it is actually smoked frog legs, which were once popular in the Zhenjiang area.

As long as it delights the palate

The second valuable aspect of the Daqian home banquet is its ability to absorb and integrate various strengths, combining elements without restrictions, utilising everything at its disposal.

Zhang Daqian pioneered the splashed-colour painting technique, showcasing a refreshing innovative spirit that astonished the world, which was valuable in allowing him to promote contemporary Chinese painting around the world. This thinking is also subtly embodied in the Daqian home banquet.

The elegant gatherings of southern Chinese cities often begin with a refined soup dish. Zhang Daqian modified the “mixed bowl” in Sichuan cooking by using ingredients such as crispy meat, chicken giblets, fish cakes, fish maw, mussels, fried tofu, mushrooms, bamboo shoots and choy sum, creating a clear broth named xiangyao (相邀, lit. invitation to meet), to open the palate and delight everyone.

The mysterious dish liuyi si (六一丝, lit. six-one silk, referring to shredded ingredients) often appeared on Zhang’s menu. The story goes that on Zhang’s 61st birthday, Chen Jianming, a Sichuan culinary master residing in Japan, came up with a special dish for the “bearded gentleman” — Zhang was known for his magnificent beard.

Chen selected six seasonal vegetables, including green bean sprouts, enoki mushrooms, green peppers, cucumbers and pickled squash, along with dried squid.

Each ingredient was sliced in shreds and quickly stir-fried over high heat; the dish featured vibrant colours and clear layered textures without being greasy, symbolising good fortune and longevity. Zhang Daqian and his guests praised it highly.

Later, Zhang incorporated this dish into his Da Feng Tang home banquet (大风堂家宴), adjusting ingredients according to the season. At summer gatherings, he would often serve this little stir-fried dish, sharing with guests its seasonal crunchy freshness. This dish also reminds me of the different yet similar Suzhou dish shisi dacai (十丝大菜, lit. ten types of shredded vegetables).

Later, “red braised seven delicacies” appeared on Zhang Daqian’s menu, with ingredients consisting of six vegetarian and one meat component: dried tofu, roasted gluten, bamboo shoots, mushrooms, wood-ear fungus, tofu skin and pork kidney. Is that not a variation of liuyi si?

Then there is “Daqian chicken cubes”, evolved from mala chicken cubes in Hunan cuisine. To achieve better texture, Zhang Daqian chose young roosters with newly grown combs, cut their meat into cubes and marinated them. The other ingredients were simple, with just celtuce leaves or stems. The seasonings included Sichuan pepper, Pixian bean paste, dry red chilli, pepper, onion, ginger and Sichuan salt. While there was a taste of Sichuan flavour, the finished dish was not overly spicy or dry, but tender, fresh and smooth, with a rich fragrance, catering to more palates.

Zhang often told his students, “How could someone who cannot appreciate fine cuisine understand art?”

When this dish was served, it immediately received acclaim from friends and fans, earning it the name Daqian chicken cubes. It quickly gained popularity in restaurants, and became a signature dish for many. Even on his 80th birthday, Zhang wanted to cook this signature dish for his guests.

Creativity at its finest

The willingness to innovate is the third valuable aspect of Zhang Daqian’s home banquets.

Zhang often told his students, “How could someone who cannot appreciate fine cuisine understand art?”

Zhang Daqian’s culinary legacy in Dunhuang

Recently, a few friends and I visited the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang to admire the art. A friend from the Dunhuang Art Institute learned of my interest in food culture and shared stories about Zhang Daqian’s time in Dunhuang.

Back then, Dunhuang was a forgotten corner, with scarce material supplies. Zhang spent over two months sketching in Dunhuang, eating and living simply. But his innate sensitivity to ingredients led him to create local dishes still served in some restaurants in Dunhuang today, for example boiled lamb, fried eggs with elm seeds, stir-fried chicken strips with young alfalfa, mushroom and lamb offal stew, and shredded chicken with jujube paste and yam.

How did he find fresh mushrooms in the vast desert? It turned out that outside his residence stood a row of poplar trees, under which mushrooms grew during summer. Though not visually appealing, they were edible and non-toxic. Every two or three days, he could gather a plateful, making them an excellent local ingredient.

Zhang Daqian drew a map based on his explorations, marking not only the routes for picking mushrooms, but also the locations with the most abundant and delicious mushrooms.

In the autumn of 1941, Nationalist Party elder and president of the Control Yuan, Yu Youren, was inspecting the newly opened Lanzhou-Xinjiang Highway in northwest China. On hearing about the visit, Zhang Daqian invited Yu to tour the Mogao Caves. After accompanying Yu’s group on the tour, which happened to be during the Mid-Autumn Festival, Zhang personally cooked a table full of “Daqian’s Dunhuang Cuisine” for his guests.

During the dinner, Zhang and Yu talked congenially about the historical and cultural significance of Mogao Caves, as well as how they should be preserved and utilised. Zhang suggested that the government nationalise the caves and establish an agency to manage, protect and research Dunhuang art. Yu enthusiastically agreed and proposed establishing a Dunhuang academy of arts. In 1944, the National Research Institute on Dunhuang Art (now known as the Dunhuang Research Academy) was founded.

I once saw a TV documentary where Zhang Daqian drew a map based on his explorations, marking not only the routes for picking mushrooms, but also the locations with the most abundant and delicious mushrooms. When he bid farewell to Dunhuang, loaded with his artwork, he gifted this “mushroom map” to Chang Shuhong, who later became the director of the National Research Institute on Dunhuang Art. Chang was deeply moved.

During our recent visit to Dunhuang, we also got to taste boiled lamb, lamb offal and mushroom soup, full of the flavour of the “Da Feng Tang Mountain Kitchen”.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “作为美食家的张大千”.