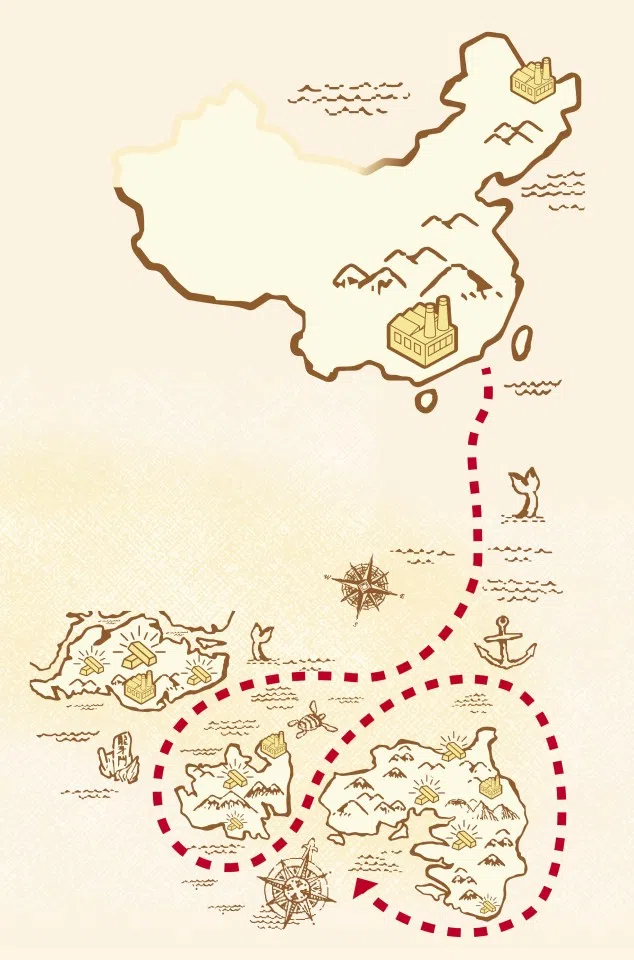

[Big read] China’s money moves south: The new frontier rising off Singapore’s coast

As China’s economy slows and US tariffs bite, a new wave of Chinese entrepreneurs is heading south — to Indonesia’s Batam and Bintan islands. Drawn by opportunity and proximity to Singapore, they’re building factories, fortunes, and a fresh start. Lianhe Zaobao journalists Lee Chee Yang and Qi Lu speak to Chinese businessmen and their Indonesian counterparts to find out more.

After lunch at a nearby mall, Mark (a pseudonym), 63, placed his suitcase in a taxi and headed for Singapore’s Tanah Merah Ferry Terminal. Ten minutes later, he was at the counter buying his ticket — a routine he knows well. After clearing security, he boarded the ferry bound for Bintan, Indonesia.

Chinese businessmen in Indonesia

For more than a year, Chinese businessman Mark has made this journey almost every two months, flying from China to Singapore before continuing by sea to Bintan. His factory there began operations in July 2024 and is now running smoothly, though his regular visits remain essential. There are still matters that require his oversight — from production adjustments to meetings with local partners.

Six months ago, Gong Hao (a pseudonym), 40, also from China, set foot on Batam for the first time — just a short ferry ride across from Bintan. The island’s infrastructure, he soon realised, lagged far behind China’s. But what it lacked in polish, it made up for in potential. Demand for factories and housing was booming. Seizing the opportunity, Gong decided to stay. He rented an office, hired more than ten local employees, and began taking on factory construction and renovation projects.

Influx of Chinese capital

Mark explained that the raw and auxiliary materials his company uses are mainly imported from Africa, the Americas, and Europe, while the finished products, such as fragrances and flavourings, are sold back to the international market. Without establishing the factory within a free-trade zone, the high import and export tax costs would have been unbearable.

In recent years, however, Chinese capital has surged into the area at an astonishing pace, standing out prominently amid what used to be a diversified landscape of foreign investors.

Batam and Bintan offer a range of tax and fee incentives to enterprises operating within their zones. Under certain conditions, these include exemptions or reductions on import duties, value-added tax, and income tax on imported goods, as well as simplified customs procedures.

As early as 1973, Batam was officially designated as an industrial development zone. In 2007, the Indonesian government further incorporated Batam, Bintan, and Karimun into its system of free-trade and free-port zones.

In the past, investors in Batam and Bintan mainly came from Singapore, Japan, Europe, and the US, with industries concentrated in electronics components, tourism, and resource processing. According to data from the Free Trade Zone (FTZ) authorities of both islands, Singapore has long been the largest source of foreign investment.

In recent years, however, Chinese capital has surged into the area at an astonishing pace, standing out prominently amid what used to be a diversified landscape of foreign investors. Taking Batam for example, figures from its FTZ authority show that Chinese investment rose from US$17.32 million in 2022 to US$51.71 million in 2023, before rocketing to US$253 million in 2024, a nearly fifteenfold increase over three years.

When China’s economy stalls: a contractor’s escape to Batam

In March 2023, Mark made his first visit to an industrial park on Bintan Island. The park’s infrastructure — roads, power supply, and water facilities — exceeded his expectations. More importantly, the factory site was only about an hour by ferry from Singapore’s port, and import–export procedures were relatively straightforward. He immediately concluded that the location met his relocation needs, signed an agreement with the park four months later, and after nearly ten months of approvals and construction, the factory was successfully established.

Mark’s case represents a proactive relocation by taking advantage of policy opportunities, whereas Gong Hao’s journey overseas was one of necessity amid debt and hardship.

Crushed by debt and with no way to recover his payments, (Gong Hao) followed a friend to Batam Island to start anew, as many peers faced the same plight.

Gong Hao had been a contractor for 15 years, taking on many government projects. But as China’s economy slowed over the past few years, many payments were left in limbo. To finish the work, he borrowed heavily from relatives and friends — yet the government funds he was promised never arrived. Today, local authorities still owe him more than 3 million RMB (US$421,250).

“I tried every possible way to get them (the local government) to pay, but it was futile. The main contractors are owed even more — some in the hundreds of millions of RMB.” Crushed by debt and with no way to recover his payments, he followed a friend to Batam Island to start anew, as many peers faced the same plight.

Lower costs and abundant natural resources

According to Wijayanto Samirin, senior economics lecturer at Paramadina University in Jakarta and former adviser to Indonesia’s vice president, China’s manufacturing sector has in recent years faced rising production costs and a complex geopolitical environment, making overseas diversification necessary. Indonesia’s relatively low labour costs and abundant natural resources provide investors with a competitive edge, making the country an increasingly attractive destination.

Wijayanto added that in the past, Chinese investment in Indonesia had focused primarily on natural resources and commodities. Now that China is expanding its manufacturing investments in Batam and Bintan, “it is a positive shift.”

This trend is reflected in Indonesia’s export data for July. According to Bloomberg, in the first half of 2025, Indonesia’s top ten exporters of solar cells and solar panels shipped US$608 million worth of panels and cells to the US. Six of those companies are based in Batam, and investigations revealed that these firms were actually owned by senior executives of Chinese solar companies. Together, they accounted for nearly 70% of Indonesia’s related exports to the US.

However, this surge of capital has not only shown up in robust industrial and trade activity — it has also stirred sensitivities involving land, communities, and the environment.

Surge of investment stirs unease

In 2023, a “green city” project by China’s Xinyi Glass on Rempang Island, adjacent to Batam, triggered fierce local opposition. The global glass and solar panel giant planned to invest US$11.6 billion to develop the project, which would require the relocation of about 7,500 residents.

Resort operators and environmentalists opposed the plan, warning that construction could threaten coral reefs and disrupt the island’s tourism ecosystem.

According to reports from Kompas and The Jakarta Globe, the project had been designated a national strategic project under former president Joko Widodo’s administration, and the relocation process began at the end of 2023. However, local residents strongly opposed the government’s resettlement plans, staging multiple protests and clashing with police.

A similar dispute emerged on Bintan Island, where Bloomberg reported that a subsidiary of China’s Nanshan Group planned to expand its industrial park in the island’s southeast and on nearby Poto Island, building aluminum smelting, steel, and petrochemical facilities, along with a port. Resort operators and environmentalists opposed the plan, warning that construction could threaten coral reefs and disrupt the island’s tourism ecosystem.

Social turmoil puts Chinese investment plans on hold

While such land and environmental conflicts represent localised project risks, Indonesia’s nationwide protests in late August 2025 expanded uncertainty to a broader scale. In Jakarta and other cities, widespread demonstrations erupted over lawmakers’ high salaries and housing allowances. Heavy-handed police crackdowns quickly inflamed tensions, leading to casualties and triggering turmoil in financial markets.

Although the wave of protests had nothing to do with foreign investors, Batam-based Gong Hao decided to suspend his company’s operations at that time, instructing employees to stay home and avoid going out. “You can’t rule out the possibility that some people, stirred by emotion, might turn their anger toward outsiders,” he said.

...over the next few years, some Chinese enterprises may drop Indonesia from their list of preferred destinations for overseas expansion. – Gao Xiaoyu, General Manager, Yard Zeal Real Estate

For Gong, such concerns were not unfounded. He had previously heard of clashes between Chinese-funded enterprises and local residents on Batam and Bintan, and he viewed this as a common potential risk for foreign investors operating in the region.

Gao Xiaoyu, general manager of Yard Zeal Real Estate, a firm that assists Chinese companies in establishing operations in Indonesia, revealed that the demonstrations had already caused some clients to back out. “Many of our clients are worried. Some have already canceled or postponed their investments in Indonesia.”

She predicted that the uncertainty arising from social unrest would likely persist into the second half of the year, and that over the next few years, some Chinese enterprises may drop Indonesia from their list of preferred destinations for overseas expansion.

However, industrial park operators and local intermediaries on the islands offered a different perspective on the recent unrest.

Both Batam and Bintan remained calm

Edmund Lai, chief marketing officer at Gallant Venture, stressed that Batam and Bintan were unaffected by the protests. “If there had really been demonstrations, my clients would have called me immediately,” he said firmly. “I can assure you that both Batam and Bintan were calm at the time — everything was normal.”

Gallant Venture is a commercial and industrial property developer that operates one industrial zone each on Batam and Bintan, with many Chinese clients among its tenants.

On 1 and 2 September, demonstrations had been announced or planned in multiple Indonesian cities, prompting heightened security in Jakarta. In Batam, Li Chengxin (pseudonym), an industrial property agent with over two decades of experience, drove around the island to see whether the unrest had spread there. “It was very safe — everyone was busy making money,” though he did notice some road closures. “Maybe the government anticipated protests, but in the end, nothing happened.”

A source familiar with the matter said that a peaceful march had indeed been planned on Batam Island, but it was called off after President Prabowo personally intervened and urged its cancellation.

Search for alternative markets

For multinational enterprises, what truly shapes long-term confidence is not just social unrest on the streets, but the uncertainty of international trade rules.

On 8 August, Reuters reported that the US plans to tighten scrutiny of transshipped goods. According to a White House executive order, products found to have concealed their origin or been rerouted illegally will face an extra 40% tariff — though what qualifies as “transshipment” remains undefined.

At present, US tariffs on Indonesian imports stand at 19%, lower than the 30% imposed on Chinese goods. An anonymous academic interviewed explained that many Chinese companies comply with Indonesian regulations by relocating key production processes to the country, thereby qualifying for “Made in Indonesia” status under rules of origin and avoiding the higher tariffs applied to Chinese exports.

“...it’s basically about ‘washing’ the country of origin.” He also conceded that, “If conditions allow, I’d want to do the same.” – Gong Hao, Chinese businessman in Batam

Gong Hao admitted that some Chinese firms overseas add minimal local processing to meet origin rules and cut tax burdens — in his words, “it’s basically about ‘washing’ the country of origin.” He also conceded that, “If conditions allow, I’d want to do the same.”

Although Gong is now focused on construction and renovation projects in Batam, he plans to build a solar panel factory that imports materials from China and exports finished products across Southeast Asia — and possibly to the US. Washington’s tariff policy, he said, remains a major concern.

Stephen Olson, a former US international trade negotiator and a visiting senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, said the first Trump administration was frustrated by the ability of Chinese companies to circumvent punitive US tariffs by routing products through third countries. So, the president is determined not to allow that to happen again in his second term, and the “transshipment provisions are clearly directed, first and foremost, towards China”.

Olson also felt that increased Chinese investment into Batam and Bintan could be driven at least in part by a desire to escape punitive US tariffs on exports from China, but it’s not necessarily the only or even the primary reason.

Deborah Elms, head of trade policy at Hinrich Foundation, chose to view this through the broader lens of global supply chain restructuring. She said that Chinese firms, like most companies globally, have recognised the risks of footprints in only one country. “Covid taught firms that diversification is important.”

Official statistics from China reflect this shift. According to the Ministry of Commerce, China’s non-financial outbound direct investment reached US$143.85 billion in 2024, up 10.5% year on year. Investment in ASEAN countries rose 12.6%, mainly flowing into Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand, with key sectors being leasing and business services, manufacturing, and wholesale and retail trade.

“A place where people have the right to take to the streets to fight for their interests,” he said, “is actually a safe place. It’s where private property isn’t protected — no matter how calm things look on the surface — that you feel truly insecure.” – Mark, Chinese businessman in Bintan

Some foreign firms turn to Indonesia’s domestic market

Gao Xiaoyu noted that many companies are now drawn to Indonesia’s vast domestic demand, fueled by its population of 270 million. “Among our clients, some no longer focus on exports — they’re developing products directly for the Indonesian market,” she said.

Mark has the same view. He observed that consumer purchasing power across Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, is rising, making it “a market with real potential” for his business. As for the recent protests and clashes, he said he was not worried, viewing them instead as “an expression of public discontent with the central government compounded by police mishandling.”

“A place where people have the right to take to the streets to fight for their interests,” he said, “is actually a safe place. It’s where private property isn’t protected — no matter how calm things look on the surface — that you feel truly insecure.”

For entrepreneurs like Mark, a sense of security comes from predictable rules, and their decision to stay or leave depends on whether costs remain manageable. Whether Batam and Bintan will become the next “gold rush havens” for Chinese enterprises remains to be seen. However, one thing is certain: capital has already arrived, and it won’t wait.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “关税与贸易战波澜四起 中企出海印尼双岛淘金”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)