China’s huge geoeconomic footprint in the Horn of Africa

China’s extensive geoeconomic footprint in the Horn of Africa spans from building a new port and the Djibouti International Free Trade Zone to developing industrial parks in Ethiopia and linking them through the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, forming an emerging economic corridor, according to US academic Chen Xiangming.

The Horn of Africa is caught in a wave of crises. The Houthis in Yemen have been launching drone attacks at commercial ships in the Red Sea while exchanging rockets with Israel amid the current war in the Middle East. Ethiopia’s federal government is dealing with the aftermath of a civil war with the Tigray region (2020-22) and its entrenched ethnic conflicts.

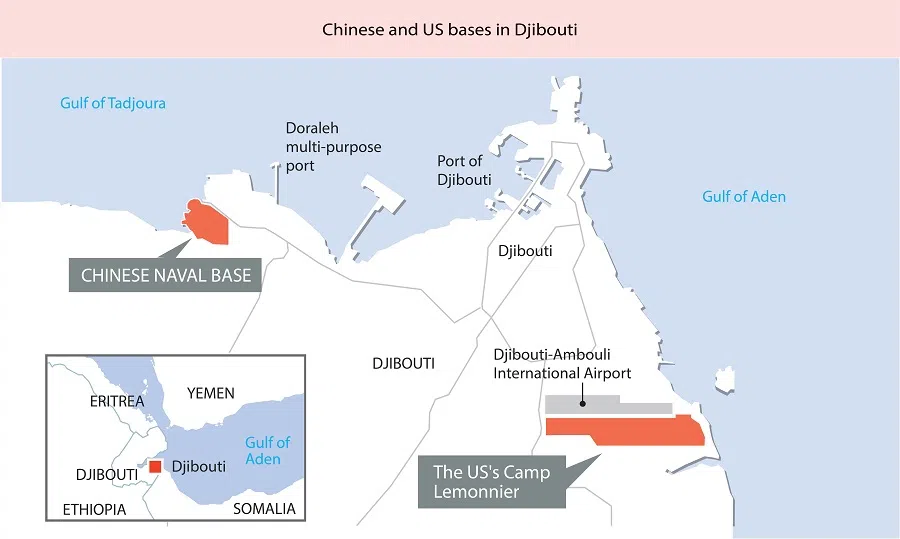

Through a geopolitical lens, China’s establishment of its only overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017 for military supplies — where US, French and Japanese military bases are also present — seemed to be a talisman in the face of the emerging great power competition. Much less known is that China has quietly spread a massive geoeconomic footprint in the Horn, primarily within and between Djibouti and Ethiopia.

Their goal is to transform Djibouti into the “Shekou of East Africa”, positioning it as a key gateway for shipping, logistics, and trade.

Located on the Gulf of Aden, Djibouti sits at the crossroads of the shipping route between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. Djibouti’s strategic location is critically important for China, which imports over one-third of its crude oil from countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran and the Gulf states.

Djibouti as a logistics gateway

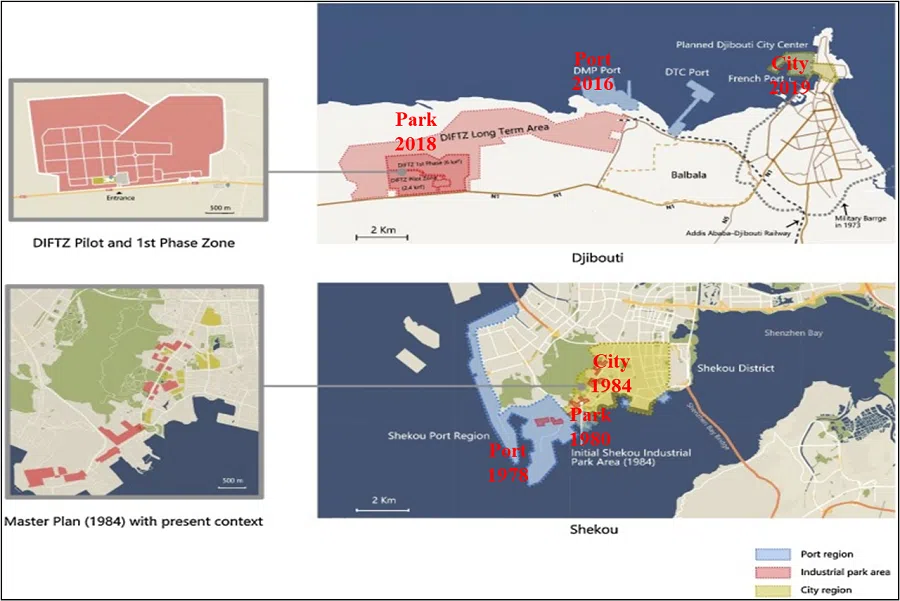

Since 2013 when the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was launched, China has engaged with Djibouti through a translocal approach. China Merchants Group (CMG), a state-owned company based in Hong Kong, has developed new logistical infrastructure at the Djibouti port via its Shekou-based subsidiary, CMPort.

Adapting the port-park-city (PPC) model of logistics-led urban development introduced in Shekou in 1979, which spurred Shenzhen’s rapid growth, CMPort aims to replicate this success in Djibouti. Their goal is to transform Djibouti into the “Shekou of East Africa”, positioning it as a key gateway for shipping, logistics, and trade.

Completed in 2017 with six berths, the new Djibouti port is capable of receiving 100,000-ton ships and handling 7.1 million tons of bulk cargo and 200,000 twenty-foot equivalent units, or TEUs.

To advance from port to park, CMG has invested US$400 million in developing the Djibouti International Free Trade Zone (DIFTZ). Upon completion, the DIFTZ will cover 48.2 square kilometres, making it the largest free trade zone in Africa. The first phase occupies 6 sq km and involves an investment of US$4 million. It includes the 2018 inauguration of a pilot zone spanning 2.4 sq km, which features subzones dedicated to logistics and warehousing.

In 2019, fDi magazine ranked the DIFTZ tenth among “The Top Ten Free Trade Zones in the World”. The DIFTZ’s resident enterprises surpassed 200 by September 2022, 300 by May 2023, and 389 by May 2024. The zone is projected to create around 6,000 jobs through the pilot zone and 50,000 jobs by 2025, and US$2.5 billion in gross output in 2035. Despite having implemented a modified port-park project in Djibouti, CMG has done relatively little about the “city” component of PPC.

... Ethiopia has prioritised labour-intensive manufacturing to raise the manufacturing share of its GDP from 4% to 17% by 2025, embracing industrial parks as the main strategy.

Shaping Ethiopia’s industrial landscape

Unlike the small port-state of Djibouti with around one million people, Ethiopia is both landlocked and Africa’s second largest nation with over 120 million people, 57% of whom in the 15-64-age group. Given its abundant working-age population and low labour cost that is 1/6-1/8 of China’s average, Ethiopia has prioritised labour-intensive manufacturing to raise the manufacturing share of its GDP from 4% to 17% by 2025, embracing industrial parks as the main strategy.

China has helped Ethiopia build manufacturing-focused special economic zones (SEZs) of both public and private ownerships, through the Overseas Trade and Economic Cooperation Zone (OTECZ) programme under the BRI.

The Eastern Industrial Zone (EIZ), Ethiopia’s first private SEZ built by companies from the Zhangjiagang Free Trade Zone in Jiangsu province, has received approval as an official OTECZ. In 2011, Huajian Group, a large private shoe company from the Chinese city of Dongguan, opened a factory in the EIZ to produce footwear for such international brands as Guess and Naturaliser.

Given the huge shoe-making labour cost differentials, the expected improvement in local labour productivity to 80% of China’s would allow Huajian to make a 15% profit, compared to the profit margin of 3-5% in southern China.

China has participated in building most of Ethiopia’s industrial parks.

Huajian also leased a large plot of land at an annual cost of US$4 per sq m — significantly lower than industrial land prices in southern China. In 2015, the company began developing the Huajian Light Industrial City, which, upon completion in 2025, will cover 500,000 sq m and include an industrial park, an office zone, and a commercial centre.

Ethiopia has developed 29 industrial parks, of which 22 are operational. This includes 16 state-owned parks and six privately-owned parks. China has participated in building most of Ethiopia’s industrial parks. For example, China’s Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) built the Hawassa Industrial Park, Ethiopia’s largest state-owned SEZ, in 2016.

Forging cross-border transport connectivity

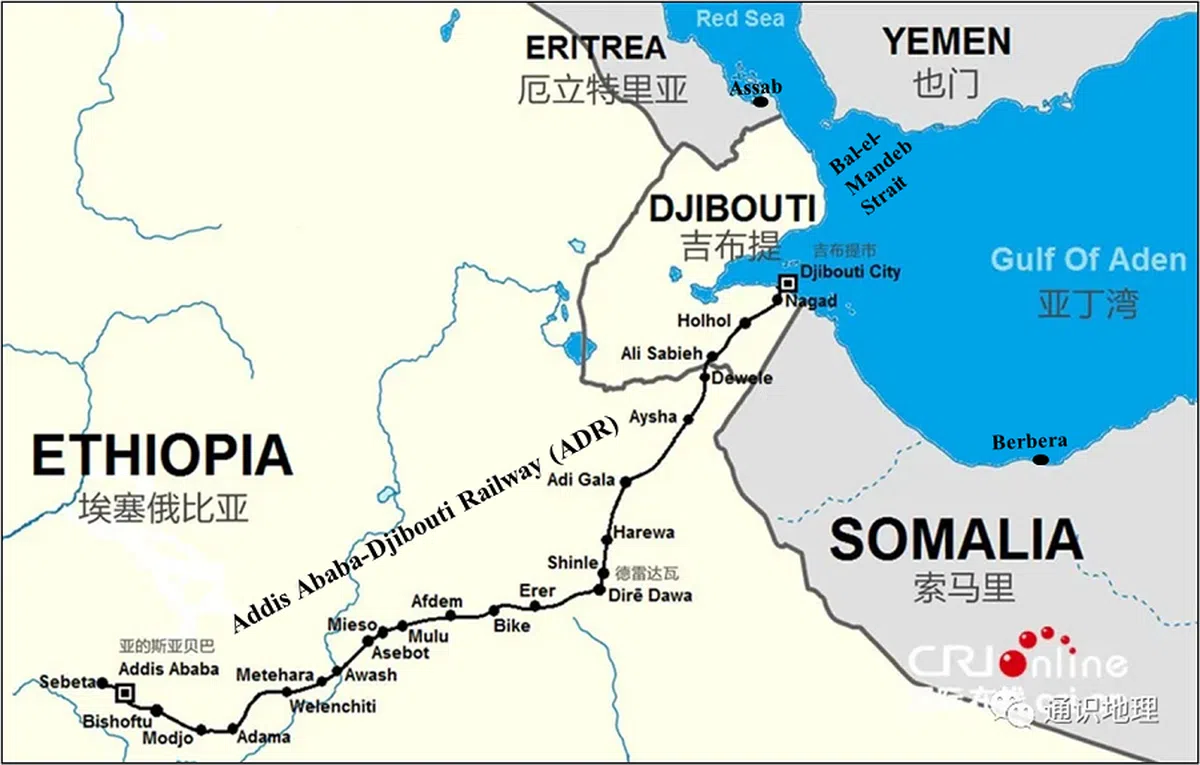

China has developed logistical infrastructure in Djibouti and industrial parks in Ethiopia through both state and non-state corporate actors, linking them via the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway (ADR).

With over 90% of Ethiopia’s exports going through Djibouti Port — which depends on Ethiopia for 70% of its port activities and one-quarter of its national revenues — the ADR allows Djibouti and landlocked Ethiopia to have a gateway-hinterland transport connection with mutual benefits.

However, contrary to common assumptions about large-scale BRI projects, these developments were not planned or coordinated by the Chinese government.

In 2012, Ethiopia secured a loan of US$2.5 billion from the Export-Import Bank of China, to cover 70% of the cost in Ethiopia, while Djibouti got US$492 million from the same source to pay for 85% of the construction on its side, with the remaining financial gap covered by the two governments.

Built jointly by CCECC — which happens to have built the Hawassa Industrial Park — and China Railway Engineering No. 2 Group Co. at a final cost of US$4 billion, the ADR was completed in 2016 and began operation in January 2018.

The ADR now carries a total of 120,000 person passengers annually while shipping over 2 million tons of cargo.

Stretching 752 kilometres and 23 stations, 19 in Ethiopia and 4 in Djibouti, the ADR is Africa’s first electrified railway, running at 160 km/hr for the passenger train and 120 km/hr for freight. The ADR’s monthly revenue exceeded US$9 million and US$10 million in October and November 2021 respectively, the best results since 2018, and 37.4% higher than in 2020.

With the passenger train, a 20-hour bus trip from Djibouti City to Dire Dawa in Ethiopia on bumpy roads has become a comfortable train ride of three hours. The ADR now carries a total of 120,000 person passengers annually while shipping over 2 million tons of cargo.

Ethiopia’s China-built industrial parks have underperformed in exports, fulfilling only 46% of the target for the 2023-34 fiscal year.

Uncertainties about future developments

From constructing a new port and the DIFTZ to developing industrial parks in Ethiopia and linking them through the ADR into an emerging economic corridor, China’s geoeconomic footprint in the Horn of Africa is wide and deep. However, the success of adapting the PPC model of logistics-led urban development to these distinct contexts depends on effective and responsive localisation.

Ethiopia’s China-built industrial parks have underperformed in exports, fulfilling only 46% of the target for the 2023-34 fiscal year. This is due to the US removing tariff-free imports from Ethiopia in 2022 and domestic ethnic conflicts.

The ADR has not lived up to its full capacity due to several challenges, including the Ethiopian government’s monopoly on rail and highway operations, which has led to irrational pricing. Additionally, issues such as unstable electricity supply and inefficient shipping links between ADR stations and nearby industrial parks have further hampered its effectiveness.

These national and cross-border constraints introduce uncertainty about the current and future impact of China’s extensive geoeconomic engagement in the Horn of Africa.