TAPI: Pipe dream or energy lifeline?

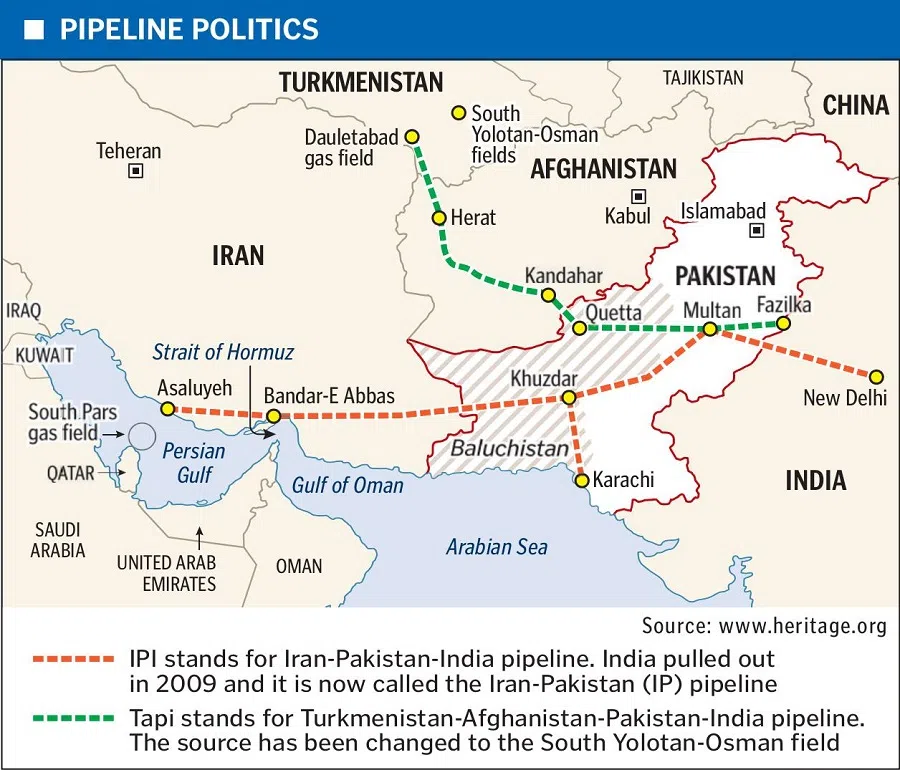

Various parties, including China, could benefit from the long-delayed Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline project. However, major security-related challenges stand in the way, says researcher Genevieve Donnellon-May.

Central Asia, a region rich in natural resources and strategically located between major markets, is often overlooked, particularly in global energy discussions. But this could soon change.

The region is interested and willing to play a crucial role in meeting South Asia’s enormous energy demands, as continued interest in major intra-regional projects like the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline shows.

This piece of critical infrastructure is poised to be a game changer in the region’s energy landscape but, so far, its journey has been fraught with formidable challenges. Will the ambitious TAPI pipeline open up new possibilities or prove a sticking point for regional relations and energy security?

... construction of the gas project has faced repeated delays. This is due in part to years of Afghan hostilities, inter-regional tensions and uncertainty in the region.

A story of repeated delays

The estimated US$10 billion TAPI pipeline is expected to cover more than 1,800 km. It is designed to annually transport up to 33 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas from Turkmenistan’s southeastern Galkynysh Gas Field, the world’s second-largest gas field in terms of gas reserves, to Pakistan and India via Afghanistan. Of the transported natural gas, Pakistan and India will receive 14 bcm via the natural gas pipeline while Afghanistan will receive 5 bcm yearly.

Initially signed in the early 1990s to provide natural gas from energy-rich Central Asia to energy-deficient South Asia, construction of the gas project has faced repeated delays. This is due in part to years of Afghan hostilities, inter-regional tensions and uncertainty in the region.

For instance, in 2018, construction began on the pipeline but was soon stopped due to security reasons after workers clearing the area were killed by unknown assailants. However, following the exit of Afghanistan by US and North Atlantic Treaty Organization forces in 2021, the gas pipeline once again became the focus of attention.

On 15 October, Turkmenistan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Rashid Meredov and Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif held a meeting in Islamabad to discuss bilateral relations and projects, including the long-awaited TAPI pipeline. This meeting follows September reports in Afghan media that “practical work” on the pipeline would soon begin, after a meeting between Meredov and Amir Khan Muttaqi, Afghanistan’s acting foreign minister.

On paper, the pipeline makes sense for all participants. Central Asia is rich in energy resources and South Asia has significant energy needs.

There are clear benefits for each country too. For Turkmenistan, the pipeline gives Ashgabat access to valuable South Asian markets, home to more than 1.75 billion people. The country’s state-owned energy company Turkmengaz is believed to hold an 85% stake in the project. The remaining three countries — Afghanistan, Pakistan and India — each hold 5%.

Diversification of export markets is a key issue given Russian company Gazprom’s decision to halt gas imports from Turkmenistan and also Turkmenistan’s continued export reliance on China.

Turkmenistan and Russia are in competition to supply natural gas to China.

Competition to supply natural gas to China

Since 2010, Beijing has been the largest customer of Turkmenistan gas and recent figures further stress the importance of the Asian emerging power to the Central Asian state. According to Business Turkmenistan, the first quarter trade turnover in 2024 between the two countries totalled almost US$2.6 billion, of which Turkmenistan’s natural gas sales to China comprised almost 92% (US$2.39 billion). Other reports state that Turkmenistan has become China’s largest gas supplier in the first half of 2024, with exports worth US$5.67 billion.

Turkmenistan and Russia are in competition to supply natural gas to China. Earlier this year, Turkmenistan reportedly ended its long-term gas contract with Russian energy corporation Gazprom while pursuing a major deal with Iraq, escalating its competition with Russia. This rivalry has intensified since 2022, when sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted Gazprom to halt European exports and pivot towards Asia.

Currently, Turkmenistan is in talks with China National Petroleum Corporation to expand gas exports via the planned Line D pipeline of the Central Asia-China pipeline. Meanwhile, Russia aims to boost its gas exports to China and Asia, including through the Sakhalin 2 project, to compensate for lost European shipments.

... security risks in Afghanistan make China hesitant to directly engage in the TAPI pipeline project, despite Beijing’s strategic interests in stabilising Afghanistan.

Stakeholder interests in TAPI

While not directly involved in the TAPI pipeline project, China is interested in development and energy projects in Central Asia, including under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which both Turkmenistan and Pakistan are members.

Beijing’s stance on initiatives like TAPI is shaped by its energy needs, regional interests and security concerns. Though adopting a cautious stance, media reports have suggested that Beijing is interested in the project which in turn could fit in with Beijing’s broader goals of regional economic integration and stability as well as diversification of energy routes. However, security risks in Afghanistan make China hesitant to directly engage in the TAPI pipeline project, despite Beijing’s strategic interests in stabilising Afghanistan.

To the southeast of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan stands to gain significantly from the project through increased investments, energy supplies, job creation and lucrative transit fees estimated between US$300 million and US$500 million. Estimates suggest that the potential transit revenues could account for an enormous 80-85% of Afghanistan’s central budget, making it a highly appealing project to the country’s leaders.

Meanwhile, both India and Pakistan are expected to gain from a new energy supply which enables them to meet increasing energy demands for growing and more urbanised populations. In the case of India, the country’s primary energy demand is expected to increase from 937 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in 2020 to between 1250 to 1500 Mtoe in 2030. The primary energy demand of Pakistan, for its part, is expected to increase from 75.5 Mtoe to 99.2 Mtoe by 2030.

... security concerns persist, particularly due to the presence of militant groups in Afghanistan, especially near the Afghan-Pakistani border, posing a continuous threat to the pipeline’s progress.

While the prospects are promising, significant challenges still lie ahead.

Difficult challenges ahead

Emerging from decades of conflict, Afghanistan is grappling with major economic and security hurdles. In particular, US-led Western economic sanctions and the international community’s refusal to recognise the Taliban as the legitimate government are linked to ongoing restrictions on women’s rights. Continuing US and European sanctions, prompted by new laws that further limit these rights and the growing presence of Al Qaeda, add to the difficulties, as noted by the National Resistance Front of Afghanistan.

Others further question Taliban’s capacity to provide skilled workers (such as engineers) to support infrastructure development, and which could remain a critical barrier to the project’s success.

Significant regional instability and security concerns must be addressed too. The Taliban has committed to ensuring the safety of the TAPI project by buying land along the pipeline’s route and pledging to provide adequate security for those involved in its construction. However, security concerns persist, particularly due to the presence of militant groups in Afghanistan, especially near the Afghan-Pakistani border, posing a continuous threat to the pipeline’s progress. Despite these challenges, Taliban leaders have reassured Turkmenistan of their commitment to protecting the pipeline.

Islamabad’s relations with Kabul have also soured since the Taliban regained power in 2021, fuelled by fears that the Taliban could control Pakistan’s energy supplies for political gain.

Inter-regional tensions should be considered as well, as strained relations between India and Pakistan show. Notably, Islamabad’s persistent diplomatic and military tensions with New Delhi are another hurdle to the materialisation of the TAPI project. India, for its part, has already raised concerns about the project’s logistical and economic aspects, such as the hidden costs of building the TAPI pipeline.

Islamabad’s relations with Kabul have also soured since the Taliban regained power in 2021, fuelled by fears that the Taliban could control Pakistan’s energy supplies for political gain. Terrorism concerns further exacerbate these fears.

The Taliban has not fulfilled its 2020 Doha Accord commitment with the US to prevent terrorist groups from using Afghan soil for attacks against Pakistan, specifically regarding the outlawed Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan. This group, which operates from Afghanistan and is responsible for numerous attacks in Pakistan, has heightened tensions between the two nations. The Taliban, however, denies these allegations.

The TAPI pipeline represents a bold initiative with the potential to transform the energy dynamics of Central and South Asia while also fostering regional cooperation. However, significant obstacles — including security challenges, (geo)political tensions, intra and inter-regional concerns — must be addressed for the project to reach its full potential. At this stage, however, this appears unlikely.