US tariffs: Punishing the least developed economies in Southeast Asia?

US tariffs target Southeast Asian supply chains, hitting Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam the hardest. While Chinese FDI is prominent in Cambodia and Myanmar, traditional investors still dominate more developed SEA economies. Academic Guanie Lim says ASEAN must prioritise multilateralism amid trade tensions and respond with strategic coherence.

On 2 April, US President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs rocked the world. Few countries were spared, not even those traditionally counted among the US’s closest allies. In Southeast Asia, the impact was especially acute. The region’s least developed economies — Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam — faced the steepest tariffs, ranging from 49% to 44%.

While disbelief and confusion were the initial reactions, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) policymakers wasted no time in coming up with responses. In Vietnam, Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh convened an emergency cabinet meeting with key economic ministries and agencies soon after day broke in Asia. In addition to voicing his concern with the 46% tariff imposed on Vietnamese products, Chinh urged calm among investors and ordered the creation of a task force to manage the unfolding situation. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet followed swiftly, offering immediate tariff concessions in exchange for negotiations with Washington.

The adage of sticking together or risk being sidelined one by one rings truest here.

Thus far, Southeast Asian leaders have largely responded individually, avoiding retaliatory measures and signalling to Washington that dialogue remains possible. As rational as this may appear, such uncoordinated responses risk exposing the region to greater threats. Any move by a member state to cut a bilateral deal with Washington — or worse, to exploit tariff disparities between neighbours — could trigger a race to the bottom, undermining both regional cohesion and negotiating power.

Amid the turbulence, there are glimmers of hope. Malaysia, the incumbent ASEAN chair, has moved swiftly to convene consultations with Indonesia, the Philippines, Brunei and Singapore. The immediate plan is to exchange views and explore the best solutions for all member states during a special ASEAN Economic Ministers’ Meeting. The adage of sticking together or risk being sidelined one by one rings truest here.

Rethinking China’s economic footprint

While this latest round of trade war may be framed as a direct salvo at China, it is also targeting the broader web of supply chains radiating from it, many of which pass through Southeast Asia. In effect, the economies hardest hit are those seen — rightly or wrongly — as channels through which Chinese firms have sidestepped earlier rounds of tariffs.

Implicit here is the notion of China’s expanding economic footprint in Southeast Asia, not least the deep purse string of its cohort of firms which have invested in the region. This anxiety was also summed up by the questions my colleagues and I had to answer during a recent hearing at the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

However, is that really the situation on the ground? A dispassionate analysis of key statistics suggests that the answer is no.

In virtually every year since 2012, Chinese FDI also ranks the lowest in Southeast Asia.

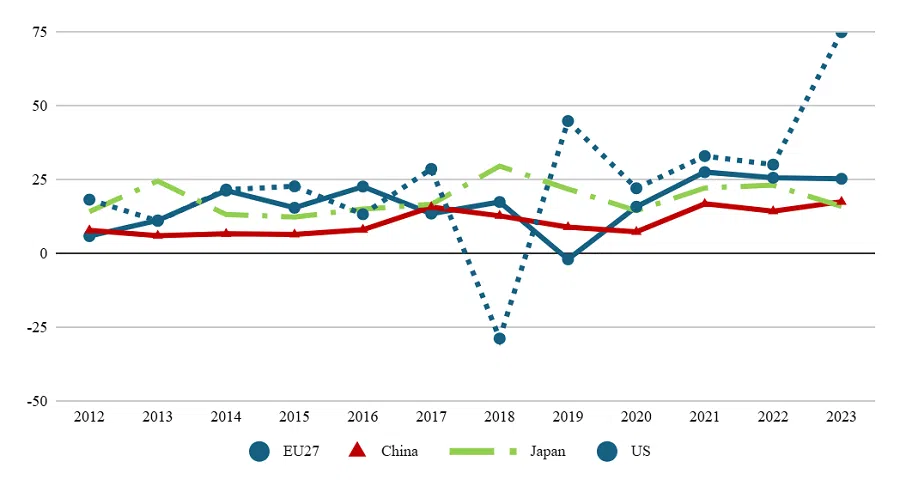

Figure 1 demonstrates that US firms have generally outinvested their contemporaries from the EU27, China, and Japan between 2012 and 2023. Although there was a sharp drop-off in 2018, US firms have rebounded strongly in the subsequent years. In 2023, US foreign direct investment (FDI) has even surpassed the combined investment of the EU27, China, and Japan.

For Chinese FDI, it has definitely grown from a rather low base, but this pace of growth is modest, at least compared to those of EU27, Japan, and the US. In virtually every year since 2012, Chinese FDI also ranks the lowest in Southeast Asia.

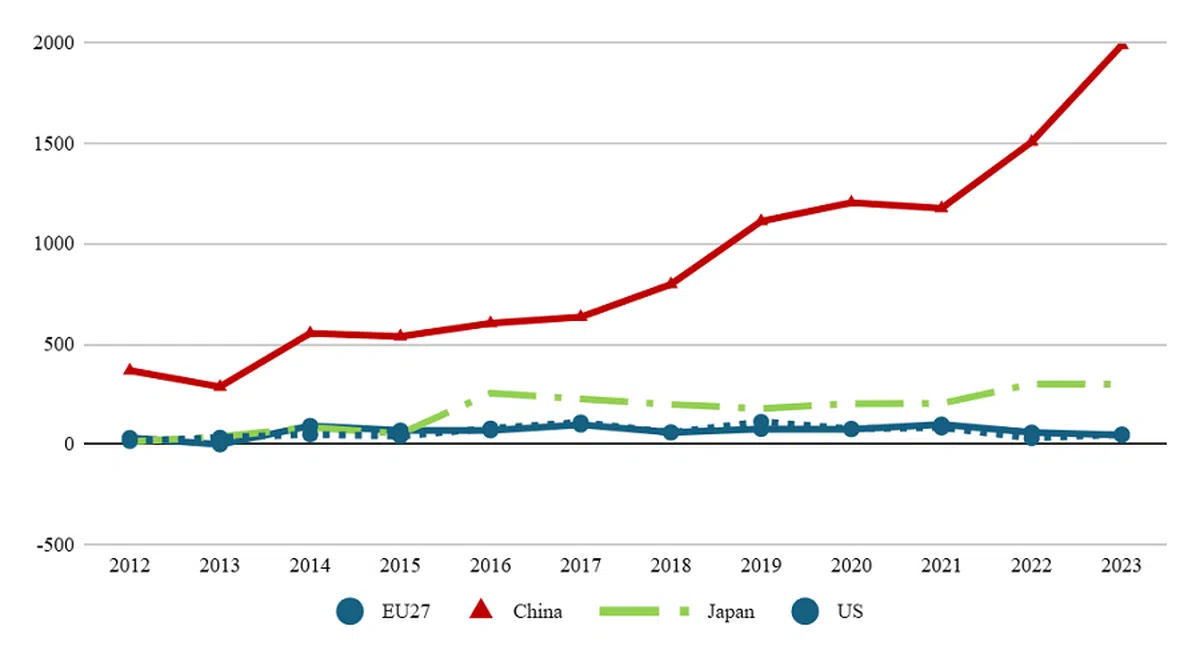

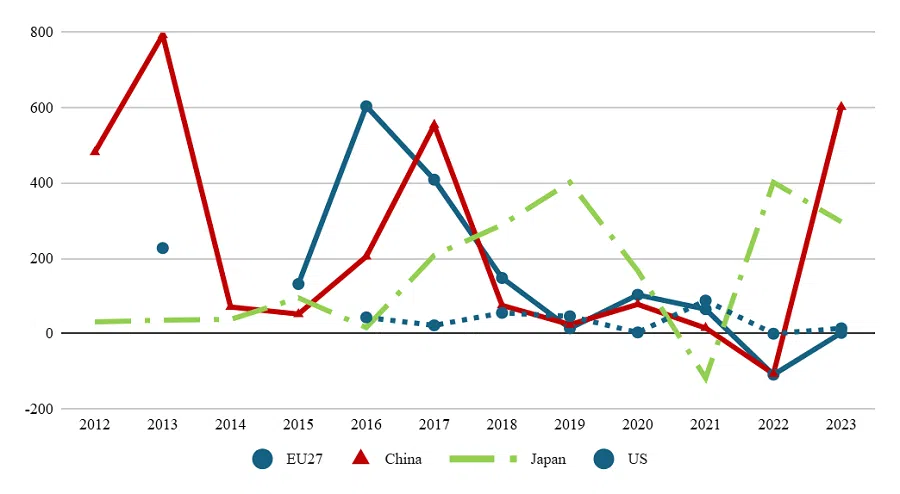

Surely there must be places where Chinese FDI has exerted the most impact? To this end, Figures 2 and 3 show that Chinese FDI is a market leader in two less developed economies of Southeast Asia: Cambodia and Myanmar. On the surface, this aligns with Washington’s concerns. Yet the reality is more nuanced.

Why Cambodia and Myanmar?

These two economies have relatively underdeveloped markets and only joined the ASEAN bloc in the late 1990s. They present high-risk, low-regulation environments that deter firms from more established nations. Chinese enterprises have stepped into this void, targeting labour-intensive industries such as real estate, petty trading, infrastructure and low-end manufacturing.

China’s dominance in Cambodia and Myanmar stems less from strategic intent than from opportunistic capital filling a void left by more cautious investors.

However, this expansion has not been without controversy. Reports have surfaced regarding illicit economic activities in Cambodia, such as money laundering through casino investment, leading to growing scepticism regarding the long-term benefits of Chinese economic involvement. In Myanmar, the ongoing political instability has also created an environment where Chinese projects have been met with local resistance due to concerns over land acquisition and environmental degradation. In short, China’s dominance in Cambodia and Myanmar stems less from strategic intent than from opportunistic capital filling a void left by more cautious investors.

Notwithstanding the above, the US’s economic presence remains formidable. For Cambodia at least, the US represents by far its largest export market. In 2024, Cambodian export to the US was worth nearly US$10 billion, followed by Vietnam (US$3.6 billion), China (US$1.7 billion), Japan (US$1.4 billion), Canada (US$1.1 billion) and Spain (US$1 billion).

This likely explains the swiftness by which the Cambodian leadership has reduced tariffs on 19 US product categories, lowering them from the maximum bound rate of 35% to an applied rate of 5%, in the hope of delaying tariff implementation and engaging in immediate negotiations. At the point of writing, the US has yet to respond to Cambodia’s request.

Between 2012 and 2023, there is no clear sign that Chinese FDI has definitively usurped the more “traditional” investors.

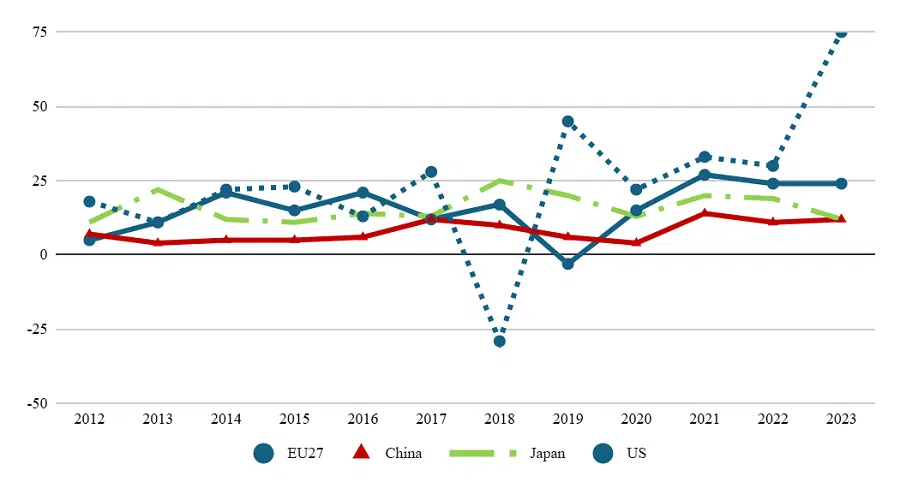

What about the situation in the larger and more mature Southeast Asian economies (i.e. Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand)? Here, one observes that these economies have also attracted large pools of capital from EU27, Japan and the US, notwithstanding China’s increasing FDI presence (see Figure 4).

Between 2012 and 2023, there is no clear sign that Chinese FDI has definitively usurped the more “traditional” investors. The dominance of these traditional investors underscores the resilience of their corporate networks, which extend beyond automotive manufacturing to high-tech industries such as semiconductors, software, and consumer electronics.

Measured response

In Malaysia, the mood post-“Liberation Day”, while worrying, is still relatively sanguine. Leveraging its role as ASEAN chair, the Malaysian government has urged greater regional solidarity. It also does not foresee a recession, although several economists polled over the weekend predict weaker economic growth in the coming months. Several factors explain this relative calm.

First, there has traditionally been frequent exchange between the bureaucracy and the American Chamber of Commerce in Malaysia. Iconic US brands like Apple, Microsoft, and Coca-Cola also continue to enjoy deep-rooted consumer loyalty. Indeed, as recently as March 2025, the chamber’s CEO, Siobhan Das, publicly reaffirmed her confidence in the resilience of US-Malaysia trade ties, despite global uncertainties.

Second, while the US has recently become Malaysia’s largest export market, it is only ranked third in overall trade volume. A government report shows that China, as of late 2024, remains Malaysia’s largest trading partner for the 16th consecutive year since 2009.

Furthermore, some players, such as Singapore, have taken an even more strategic approach toward investment diversification. The city-state has long positioned itself as a global financial hub, attracting investment not only from China but also Western countries and regional powerhouses such as India and South Korea. Singapore’s robust regulatory framework ensures that no single country wields disproportionate economic influence over it.

This balanced approach is, to a certain degree, reflected in its trade profile. Singapore is the only ASEAN member state which runs a trade deficit against the US, meaning that it was shielded from the full force of US tariffs — receiving only the baseline 10% rate. This is not to say that Singapore will “go it alone”. Indeed, in a widely circulated online message, Singaporean Prime Minister Lawrence Wong has urged for calm and vigilance, in addition to exhorting regional and international cooperation with like-minded countries.

... ASEAN must resist the temptation to splinter. It should double down on multilateralism, despite the uneven economic dependencies among its members.

Navigating the storm with a better compass

The “Liberation Day” tariff shock may yet prove to be a stress test for ASEAN’s institutional maturity. It offers the region’s policymakers an opportunity to reassert a collective voice, reframe its role in the global supply chain, and rethink its exposure to geopolitical volatility. While Washington may believe it is targeting China, the collateral damage risks disrupting regional economies with little say in the great power rivalry unfolding above them.

Now more than ever, ASEAN must resist the temptation to splinter. It should double down on multilateralism, despite the uneven economic dependencies among its members. That means rejecting simplistic narratives and investing in a deeper understanding of the region’s economic realities.

The coming weeks will be messy. However, if Southeast Asia can respond with strategic coherence, institutional solidarity, and a clear-eyed view of its investment fundamentals, it will not only weather the storm, but also emerge stronger.