Vietnam amid great power rivalry: Is it playing the economic game well enough?

Vietnam’s uneven industrialisation experience reveals the limits of a pro-international trade and pro-FDI strategy, says academic Guanie Lim. To move beyond the role of assembler and connector, it could adopt some of China’s approaches.

In recent years, Vietnam, along with several high-growth economies, has been termed a “connector economy”. The idea was simple but powerful: by aligning with both China and the US while staying neutral, these economies could position themselves as critical intermediaries in the fragmented global supply chain.

The optimism surrounding this carefully balanced model was dashed in early April 2025 when US President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs announcement sent shockwaves throughout the world, hitting economies reliant on the US market especially hard.

Vietnam, slapped with a punishing 46% rate, was among the worst affected. Hanoi swiftly sought diplomatic redress and rallied support from its Southeast Asian neighbours, but thus far the signs are not optimistic. In particular, US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick has dug his heels in, claiming that the US will not reciprocate even if Vietnam removes all tariffs on American goods. The message here is clear — Vietnam has grown incredibly dependent on what has become a fragile international trade architecture.

While Vietnam is deeply embedded in “Factory Asia”, it lacks the industrial resilience to withstand major external shocks.

Vietnam’s vulnerabilities

This vulnerability is not new. Lest we forget, for much of the past decade, the US Department of Treasury has launched investigations into alleged currency manipulation by Vietnam. The premise is that Vietnam intentionally undervalues its currency to gain an export advantage. One only needs to look at the November 2023 decision by the Treasury department to place Vietnam on its “monitoring list” for currency manipulation. This incident came merely two months after the upgrade of US-Vietnam relations to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, in addition to the supposedly positive ties between both nations and Vietnam’s membership in the (initially US-driven) Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Nor is Vietnam’s vulnerability limited to its ties with the US. During the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, thousands of trucks were held up at the Chinese-Vietnamese border following reports that imported Covid-19 cases had been detected in China’s Guangxi province. The congestion was so severe that the Vietnamese trade ministry publicly pleaded with the Guangxi authorities to take urgent redressing measures, which normally would have been resolved through behind-the-scenes dialogue.

At the heart of such fragility lies an uncomfortable truth. While Vietnam is deeply embedded in “Factory Asia”, it lacks the industrial resilience to withstand major external shocks. This is particularly evident in its reliance on foreign direct investment (FDI), long the centrepiece of Vietnam’s development strategy since the 1986 Doi Moi (renovation) economic reforms. High-profile visits, such as Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang’s late 2024 tour, reflect Hanoi’s continuing effort to woo global capital. Earlier wins include Samsung’s Thai Nguyen mega-facility, which now produces most of its smartphones. Yet these success stories mask a more sobering reality: much of the investment is confined to export-processing zones, with minimal spillovers to local firms or technological deepening.

... state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have largely languished. Propped up by subsidies, they dominate sheltered sectors like finance and utilities, with modest presence in export markets and high-tech manufacturing.

SOEs growing bigger yet weaker

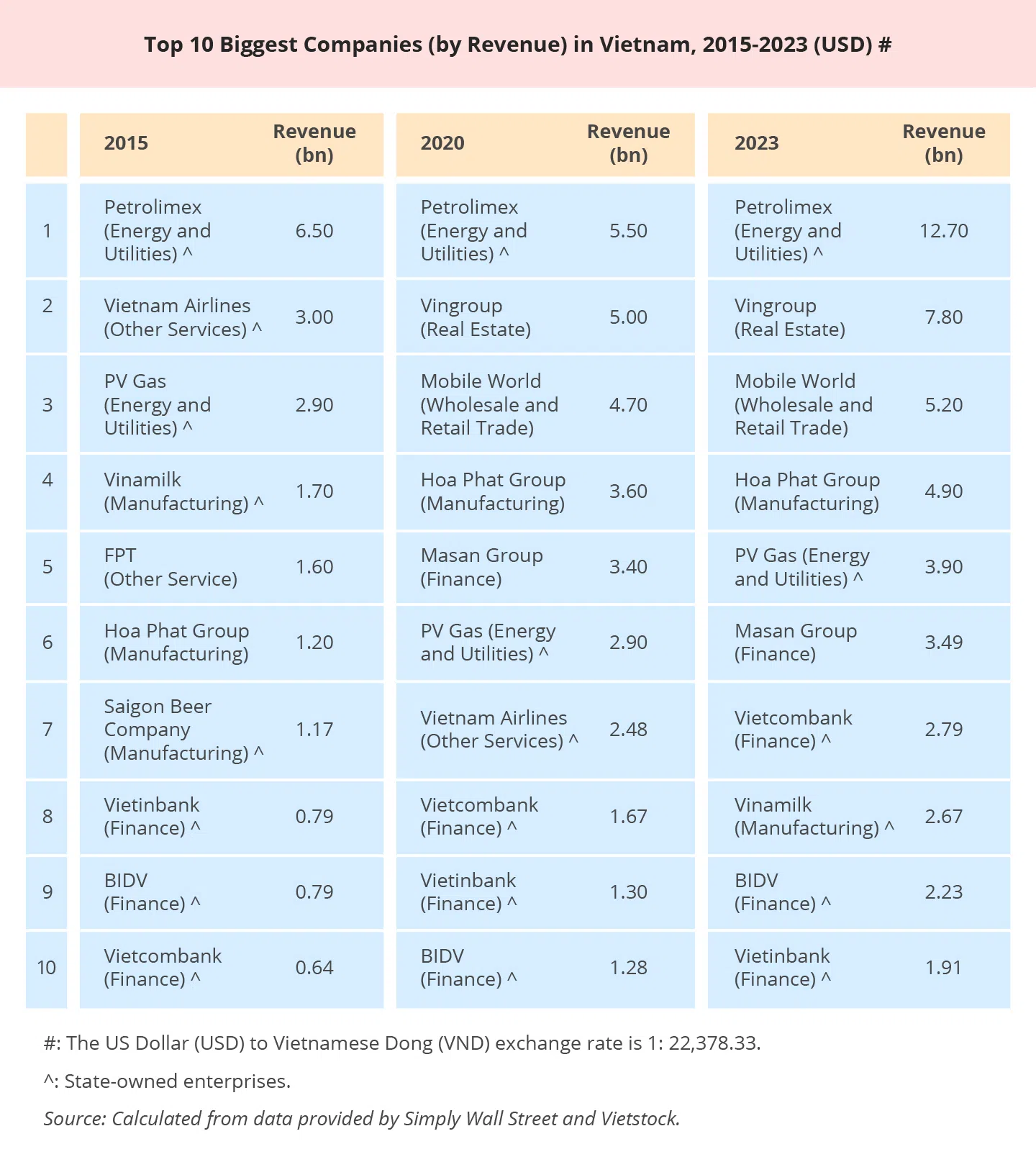

Indeed, foreign-invested enterprises now account for a staggering 74.2% of Vietnamese exports, up from 47% in 2000. Meanwhile, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have largely languished. Propped up by subsidies, they dominate sheltered sectors like finance and utilities, with modest presence in export markets and high-tech manufacturing. Only two manufacturing SOEs — Saigon Beer Company and Vinamilk — ranked among the top ten firms by revenue between 2015 and 2023 (see table above). Worse, they are agri-food manufacturers whose products and processes are not typically technology-intensive. Additionally, Saigon Beer Company and Vinamilk derive most of their revenue from the Vietnamese market, with only very little export activities.

Contrast the Vietnamese experience with China’s. While China has yet to offer readymade examples of SOEs that excel in cutting-edge manufacturing, momentum is building in the mid- and low-tech industrial spectrum. In steel manufacturing, China Baowu Steel Group has emerged as the largest player in the world, even if its productivity still lags that of global peers. In automobiles, the “Big Four” SOEs (SAIC, FAW, Dongfeng and Changan) have carved a niche for themselves in the production of affordable, mass-market vehicles. While far from flawless, these examples underscore a level of industrial coordination absent in the curation of Vietnam’s SOEs.

The aggregate outcome is that the Vietnamese economy has become increasingly polarised.

What about the Vietnamese private firms, long seen as the dynamic alternative to the SOEs, then? They have indeed increased their presence in the top ten list. In 2015, only two private firms made it into the list, but four of them were represented in the subsequent years. However, these private firms, like their SOE counterparts, tend to operate in industries with low technological complexity, limited room for export growth and few opportunities for upgrading. Hoa Phat Group stands as a rare exception with its forays into steel manufacturing. The rest remains entrenched in wholesale and retail trade, finance and real estate — industries that offer scale, but little transformative potential.

The aggregate outcome is that the Vietnamese economy has become increasingly polarised. The industrial landscape resembles several silos operating in isolation: globally-linked FDI firms, stagnant SOEs and low-capability domestic firms. As a consequence, the prospects for building a robust domestic industrial ecosystem aimed at capturing global market share through long-term skill development in key manufactured goods appear bleak.

Limits of a pro-international trade and pro-FDI strategy

The Southeast Asian nation’s uneven industrialisation experience reveals the limits of a pro-international trade and pro-FDI strategy. As the economy matures and external shocks become more frequent, the Southeast Asian nation must confront a difficult transition, shifting gears from being a passive beneficiary of globalisation to an active architect of industrial capability.

The challenge ahead is clear. Vietnam must move beyond the role of assembler and connector. This does not mean a wholesale rejection of global trade and FDI, but a recalibration to serve a broader vision of national resilience and technological depth. This means rethinking how domestic firms, especially in manufacturing, are positioned within global production networks. This also means pushing firms out of their comfort zones, incentivising a scale up in tradable, technology-intensive industries.

Vietnam need not look far for inspiration. Since its 1978 reform and opening up, China has groomed a generation of business groups across a range of industries. While Chinese SOEs have made only modest inroads into high-tech manufacturing, some progress has still been made in mass-market goods. More importantly, Chinese private firms have grown in ambition and prowess. Companies like BYD (automobile) and Xiaomi (consumer electronics) exemplify the rise of non-SOE “national champions”. Their rise, however, did not occur in isolation or by accident.

These private businesses benefited from the cumulative upgrading of China’s broader industrial ecosystem, leveraging supplier networks and manufacturing clusters that built up their know-how through years of hard, iterative learning in unglamorous industries like textiles and footwear. It is this grounded, incremental path — not a romantic leap forward — that Vietnam’s policymakers would do well to study and adapt.

This essay is a shortened and updated version of “Vietnam’s Growing Economic Integration with the World: More or Less Asian?” published in Asia Europe Journal.