[Future of China] China's economy now and in the future

Amid the difficulties in analysing and forecasting macroeconomic conditions, economist Chen Kang likens their changes to a unique game of tug of war between the bulls and the bears - in which economic reforms, policies and outcomes are interpreted differently among the players, and the current outcome encapsulates the people's aggregate response. However, the big question is whether China will press on with economic reforms despite all the challenges. This is the third in a five-part series of articles on the future of China.

The global macroeconomy has remained sluggish since Russia invaded Ukraine in February this year, which caused food shortages, increased oil prices and higher inflation. Germany, the engine of Europe's economic growth, is in trouble because of its high dependence on Russian oil and gas, and its economy was stagnant in Q2 2022.

The US Federal Reserve has increased the benchmark Federal funds rate by 225 basis points in four successive rate hikes in order to control inflation. The tightened monetary policy and withdrawal of fiscal stimulus have dampened the US's economic recovery from Covid-19, resulting in economic contraction in the first two quarters of this year.

Macroeconomic conditions are very difficult to analyse and forecast...

China's economy grew by just 0.4% year-on-year in the second quarter of the year, and the first two quarters this year contracted quarter-on-quarter. The recently announced July figure was also lower than expected. Apart from the unfavourable global conditions, China faces several domestic challenges. In late July, the IMF again lowered its annual economic growth forecast for China to 3.3%, which is a far cry from the Chinese government's 5.5% target at the start of the year.

A macroeconomic tug of war

Macroeconomic conditions are very difficult to analyse and forecast; their changes can be likened to a unique game of tug of war between two teams - the bulls and the bears - in which the number of participants is not fixed. Neither the players nor the spectators could see the contest itself, and could only grasp the situation based on the data collected and published.

The tug of war has three features. First, each team has some members with firm beliefs, so they interpret the same information differently. For example, the People's Bank of China (PBOC) trimmed the key rate (the medium-term lending facility rate) by ten basis points (bps) on 15 August, and a week later cut its five-year loan prime rate by 15 bps. Members of the bulls team would give a positive "bulls' explanation" as they believe that these developments would improve credit, stimulate investments and encourage property purchases.

Members of the bears team, however, would offer "a bears' conclusion" that the central bank's rate cuts at a time of increased inflationary pressures are definitely not a good sign, indicating grim economic conditions, and that lowering the loan prime rate would not improve the troubled property market.

The second feature of the tug of war is its many non-neutral spectators watching from the sidelines and sitting on the fence for the time being. As permitted by the rules of the contest, they would enter the arena to join the tug of war when encouraged by others' actions or when they feel that the outcome is clear.

Third, the rules of the contest also permit the participants to withdraw from the contest to become spectators or join the other team at any time. The different interpretations of the information, the spectators' actions or inaction, and the participants' withdrawal or defection have an impact on the outcome of the tug of war.

As the current macroeconomic models do not have an effective way to aggregate individuals' actions and interactions at the micro level to form a clear macro picture, their ability to analyse and forecast is greatly limited.

Nonetheless, we can still focus on key indicators to make some crude conclusions about the macroeconomic trends. Some published data are indicative of the short-term status of the tug of war, while others can be used to analyse the mid to long-term situation.

Short-term confidence indicators hard hit by Covid-19

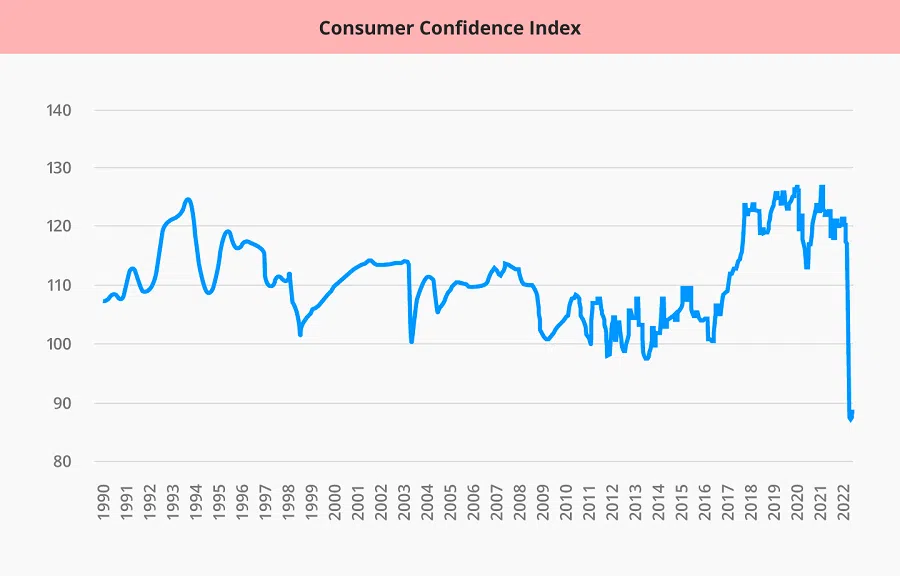

The Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) and the Business Climate Index (BCI) are two useful indicators for analysing short-term changes. China's National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) has published the monthly CCI since 1990. Chart 1 shows that the CCI has clearly begun to decline in March this year, averaging 87.5 from April to June, which is 30.9 points below the average of 118.4 from January to March.

... the recent decline in consumer confidence is largely related to the strict dynamic zero-Covid policy.

This sharp decline is unprecedented in the past 30 years, which has seen the late 1990s SOE (state-owned enterprises) reforms to bring the larger enterprises under the government's control while privatising or closing the smaller ones; the 2008-2009 global financial crisis; and the Covid-19 outbreak in 2020.

A detailed observation of the CCI would surmise that the recent decline in consumer confidence is largely related to the strict dynamic zero-Covid policy.

The CCI consists of three components: income, employment and consumption. The income of employees of enterprises that are unable to operate as usual due to "static management" (静态管理, i.e., putting normal life on pause) is greatly affected. If the enterprise shutters, the employees will lose their jobs and income. Even for those who are guaranteed a basic salary, their performance-based income and bonuses will be greatly reduced. Evidently, these people will join the bears team by being careful in consumer spending.

Unemployment or the increased likelihood of unemployment will affect consumption. Notably, the unemployment rate of 16 to 24-year-olds has steadily climbed this year, rising from 14.3% at the end of last year to 19.9% in July this year. Their struggle to secure employment could largely be due to the hiring freeze or reduction in new hires by enterprises. Consequently, consumer spending of these youths and their families is negatively affected.

Consumption willingness is directly affected by the repeated disruptions to business activities caused by Covid-19 and frequent PCR tests. Stories of people trapped in shopping malls, airports and on highways will also affect the willingness to travel. The foregoing discussions show that the battered consumer confidence can only be partially restored with the easing of Covid-19 measures as the pandemic wanes, but there will be some lasting impacts.

When confidence is lacking, consumers will tighten their purse strings. The total retail sales of consumer goods from January to July this year has decreased by 0.2% year-on-year, or even lower when taking inflation into account.

The BCI, which affects investor confidence, is another index used to analyse short-term changes. The NBS has published this index quarterly since 1999. Business confidence reached a low of 105.6 in Q1 2009 during the global financial crisis. The historical lowest, however, was 88.2 in Q1 2020 at the start of the Covid-19 outbreak.

The BCI has continued to decline since the middle of last year, from 125.2 in Q1 2021 to 112.7 in Q1 2022. The Covid-19 impact on the various industries is evident: hospitality and F&B are the hardest hit with the index falling by 42.8 in the same period. Meanwhile, the index for manufacturing has declined by 19.0 and that for wholesale and retail has fallen by 14.6.

The bears' upper hand in the current investment climate can be explained by the increased ownership risks, the restrictions on informal financing channels and the sluggish property market.

Mid- and long-term factors affecting investments

As the BCI is a short-term indicator, it cannot be used to forecast mid- to long-term investments. We need other data to assess the investment strategy in the tug-of-war between the bulls and the bears.

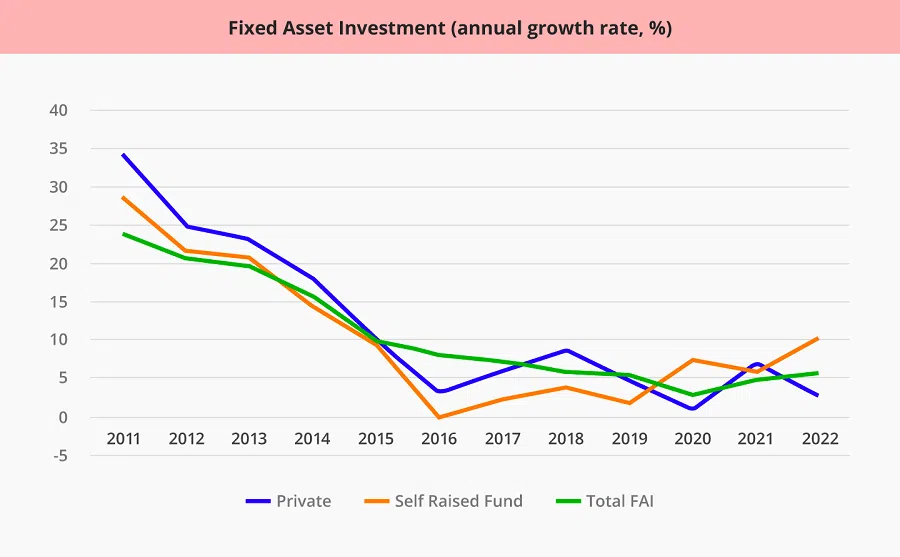

Chart 2 shows an interesting trend, whereby even prior to Covid-19 the growth of China's fixed asset investment (FAI) decreased from 23.8% in 2011 to 8.1% in 2016 and 5.4% in 2019. The trend is unrelated to the Covid-19 control measures, and cannot be explained by external changes, such as the tense China-US relations and the overwhelming pushback against globalisation.

The bears' upper hand in the current investment climate can be explained by the increased ownership risks, the restrictions on informal financing channels and the sluggish property market.

First, it is evident from Chart 2 that the growth of private FAI, which accounts for 60% of the total FAI, is highly correlated to the growth of total FAI. In recent years, the ownership and regulatory risks to private FAI have significantly increased. Private enterprises are subject to tougher regulations and stricter treatment in terms of anti-corruption, environmental protection, financial deleveraging and anti-trust.

Although some Chinese government officials talked about adopting the principle of "competitive neutrality" to deal with enterprises of different ownership, and China's leader tried to boost business confidence by stating that "private enterprises and entrepreneurs are family", the environment for the survival of private enterprises has not significantly changed. On the contrary, they have borne the brunt of the recent regulatory measures to "prevent disorderly capital expansion". The increase in ownership risks has significantly reduced the growth of private investments.

Second, the stagnation in China's financial reform has resulted in severe financial disintermediation, while the strict regulation of informal financing channels has reduced investment and financing activities and stagnated financial innovation. Data from 2017 show that bank loans account for only 11.3% of FAI, with 65.3% from self-raised funds and 16.9% from other funding sources.

In the black boxes that are "self-raised funds" and "other funding sources", much of the financing comes from informal financing activities, such as fund-raising from relatives and friends, enterprise self-financing, and borrowing from shadow banks or underground lenders. Private investments that are snubbed by banks and capital markets often rely on these informal financing channels, which have been strictly regulated in recent years, thus limiting the sources of self-raised funds.

In Chart 2, the growth of FAI through self-raised funds is highly correlated to the growth of total FAI and private investments. This illustrates that the slowdown in private investments is closely linked to the strict regulation of financing channels for private enterprises.

... the growth of residential investments has rapidly declined since 2012, from 30% in 2011 to 16.7% in 2013 and -0.2% in 2015, evidently caused by unaffordable property prices, an ageing population and high vacancy rates.

Third, residential fixed investments exceed 20% of the total FAI. Since the banks established the "three red lines" that set thresholds on borrowings last year, property developers are generally cash-strapped, resulting in a recent spate of problems such as "rotten-tail" (unfinished) properties and property buyers withholding mortgage repayments. However, the growth of residential investments has rapidly declined since 2012, from 30% in 2011 to 16.7% in 2013 and -0.2% in 2015, evidently caused by unaffordable property prices, an ageing population and high vacancy rates.

According to a PBOC survey of its urban customers in June 2018, 36.5% of the respondents expected property prices to rise. In June this year, the figure fell to 16.2%. In the first half of this year, property investments declined by 5.4%, property sales decreased by 28.9%, and the land sales area fell by 48.3%. These data indicate the status of the tug-of-war between the bears and the bulls in the property market.

Currently, most people believe that property prices will not increase further, and property speculation has ceased. While property speculators have stopped purchasing properties, owner-occupiers now believe that properties are priced too high to purchase. This deadlock in the property market has affected local governments' income from land sales, which in turn causes them to be conservative when pump-priming economic growth.

Financial industry lost direction amid high confidence

The above analysis shows a dilemma. China's market reforms have borrowed from the Eastern European experience by starting with the market for products and services and being very cautious about developing the markets for productive factors (especially the capital market), thus taking a "one step forward and two steps back" approach.

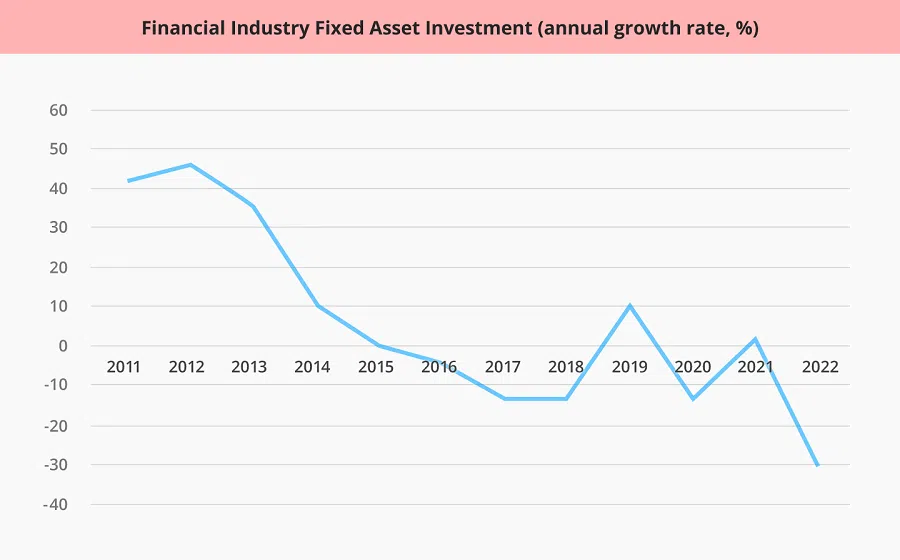

Nevertheless, the broad direction of financial marketisation is quite clear. Capital market reforms have continued after the 2008 global financial crisis, including the successive liberalisation in businesses such as trusts, insurance, bonds and private banking. Progress has also been made in RMB internationalisation and capital account convertibility.

How should financial market reforms continue, and which model should China use? There are yet no answers to these questions, and the financial industry seems to have lost direction amid high confidence in the "chosen path".

However, the global financial crisis has also made some people lose confidence in the market economy and instead laud the "China model". They have boosted the Chinese government's confidence in its current economic system while gradually weakening its willingness to press on with financial marketisation.

After China's stock market crash in 2015, government interventions in financial activities have become increasingly frequent. How should financial market reforms continue, and which model should China use? There are yet no answers to these questions, and the financial industry seems to have lost direction amid high confidence in the "chosen path".

Chart 3 shows that the growth of the financial industry FAI has decreased from 46.2% in 2012 to 0.3% in 2015, and it has been in negative territory since, with the exception of 2019. It has further declined by 30% in the first seven months of this year, which affirms the conclusion that the financial industry has lost its way.

How can the market play a decisive role?

In the 1980s, emerging out of China's dual pricing system (the government control pricing and the free market pricing systems) were profiteering government officials (官倒爷) who used their authority to obtain sought-after products at the controlled prices to sell at the higher market prices. Many have still not forgotten the huge discontent among the people caused by these officials, whose existence indicates the lack of thoroughness of market reforms.

These profiteers vanished after the abolition of the dual pricing system and the liberalisation of the market for products and services. Fortunately, China's leader at the time did not waver in the debate on whether the market should be "surnamed socialism or capitalism" that determined the direction of the reforms, and resolutely chose the path of marketisation that ended China's shortage economy inherited from the central planning.

However, due to the stagnation in reforms, the dual pricing system persisted for a long time in the transactions of capital, land and other factors of production. Profiteering by those in power continued, albeit in a less obvious manner. The huge profits attracted many rent-seeking activities, which became the main reason for corruption, power-for-money deals, and income inequality. Evidently, the corruption cases in recent years are mostly related to the financial industry, often involving huge sums of money.

... abandoning market reforms will only lead to common poverty instead, as maintaining the status quo will create more opportunities for corruption, increase income inequality, render the use of capital increasingly inefficient, and further reduce investments and innovation.

Those who do not understand this process may be misled into thinking that these are the consequences of the market economy, and that the abolition of market reforms will reduce corruption and help China achieve the goal of common prosperity. However, the real reason is the stagnation of market reforms.

The profiteering opportunities will peter out with capital marketisation and the abolition of the dual pricing system. Meanwhile, abandoning market reforms will only lead to common poverty instead, as maintaining the status quo will create more opportunities for corruption, increase income inequality, render the use of capital increasingly inefficient, and further reduce investments and innovation.

"Let the market play the decisive role in allocating resources and let the government play its functions better..." - The communique of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the CPC in 2013

Some believe that China's currently sluggish economy will rapidly improve with the waning of Covid-19. However, it is not so simple, as the above analysis shows. The communique of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the CPC in 2013 has articulated to "let the market play the decisive role in allocating resources and let the government play its functions better".

The way in which this statement is understood and the manner in which it is implemented are essentially at the core of the tug-of-war between the bulls and the bears. The current outcome encapsulates the people's aggregate response to the Chinese government's preferences revealed during the past decade. Managing the people's expectations and maintaining their confidence are of crucial importance to the nation's economic stability.

Related: [Future of China] Xi Jinping and the world: Retrospect and prospect | [Future of China] Chinese youth under Xi Jinping's Red Flag: Political participation as a route to riches | [Future of China] China's ten-year-old BRI needs a revamp | [Future of China] China's BRI seems irreplaceable, for now | Huawei founder: Global economic outlook will be grim for next few years | Can the world survive these six crises? | China's economic recovery has become a political issue | Financial decoupling: China's next step amid intensifying China-US rivalry? | China's economic crisis is a ticking time bomb

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)