[Photos] Conquest, assimilation and diversity: How minority cultures shaped China

A lesser-known fact about China is that it is ethnically diverse. Though the nation is predominantly Han Chinese, it is also home to 55 other officially recognised ethnic minorities. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao tells us more about the history, culture and integration of these minority groups in China.

(Photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao, unless otherwise stated.)

China has five major ethnic groups — Han, Manchu, Mongol, Hui, and Tibetan — while the government officially recognises 56 ethnic groups. The development of Chinese civilisation is essentially a process of mutual integration and interaction between these different ethnic groups. In every dynasty, there has been ethnic integration and cultural exchanges, creating a rich historical landscape. This process has also led to ethnic and cultural overlaps between China and its neighbouring countries.

China’s diverse past

Reviewing the history of China’s ethnic development is almost synonymous with tracing Chinese history itself, beginning from its origins. The Han ethnic group, which comprises about 92% of China’s population, includes about 1.3 billion people, making it the largest single ethnic population in the world, spread across the globe. Their origins can be traced back about 4,000 years ago to along the Yellow River, where they first established an agricultural civilisation.

Early Chinese state structures took the form of tribal alliances, with a common ancestry linked to figures like the Yellow Emperor (黃帝 Huangdi) and the Flame Emperor (炎帝 Yandi). This period saw the rise of the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties. By the end of the Zhou dynasty, around 2,500 years ago, the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period — characterised by intense competition among regional lords — began.

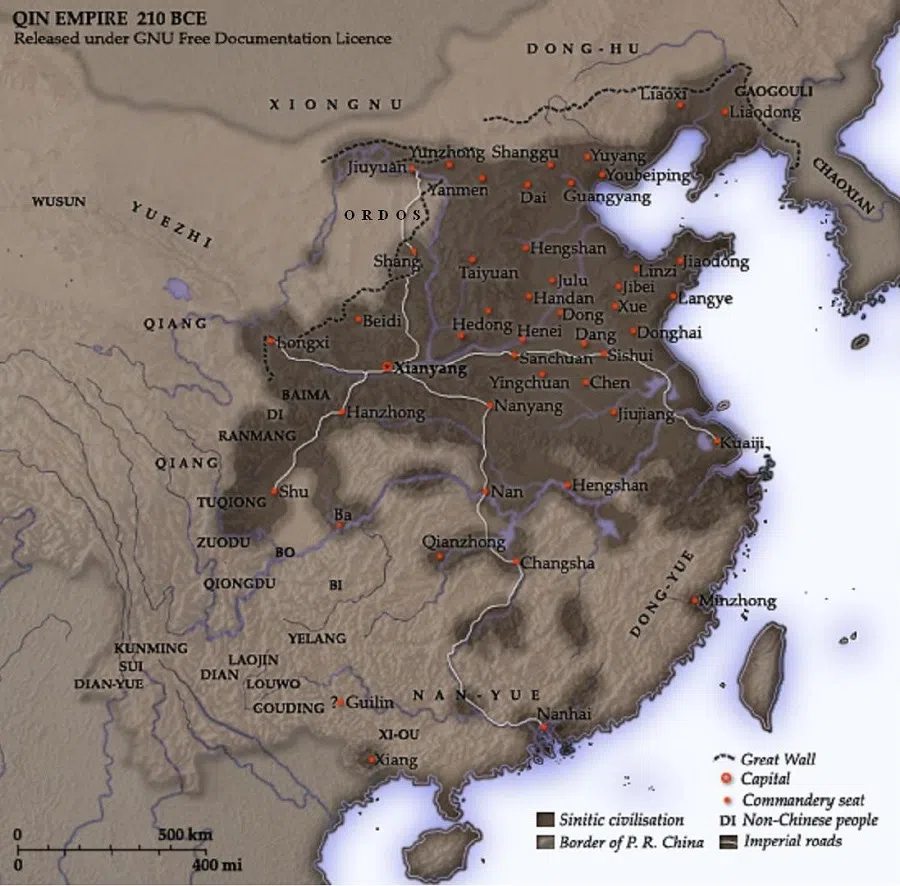

Later, the King of Qin, Ying Zheng, carried out national reforms to strengthen the state’s power and military, eventually unifying the seven warring states to form China’s first centralised authoritarian empire — the Qin dynasty. Ying Zheng became China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang.

Though his reign was short-lived, Qin Shi Huang ruled with an iron fist and established a powerful state. The territory of his empire extended west to Lintao and east to Liaodong, and the Great Wall marked its northern boundary. It reached the Sichuan region in the southwest, present-day Guangdong and northern Vietnam in the south, and the East China Sea and the Taiwan Strait in the southeast. During this period, China engaged in intensive interactions with surrounding ethnic minority groups.

The term “Han ethnic group” used today is a political designation referring to the unified ethnic groups during the Han dynasty.

To defend against the northern nomadic tribes, Qin Shi Huang mobilised a vast workforce to construct the earliest version of the Great Wall. He also standardised the Chinese writing system and measurements. The Chinese characters he unified more than 2,200 years ago are still largely in use today, highlighting his significant role in shaping China’s cultural continuity and stability. It is even said that the Western name for China originates from “Qin” (Chin). During this period, the names and distribution of northern ethnic groups began to appear on China’s maps.

The Han dynasty

Soon after the death of Qin Shi Huang, China quickly fell into internal chaos. The previously conquered seven states re-emerged, but instead of restoring their original kingdoms, they continued under the centralised system of the Qin dynasty, establishing the Han empire, or Han dynasty. The term “Han ethnic group” used today is a political designation referring to the unified ethnic groups during the Han dynasty.

The Han dynasty, one of China’s most powerful, initially faced invasions from northern nomadic tribes. Under Emperor Wu of Han (Han Wudi, birth name Liu Che), the Han strengthened its military and sent envoys to Central Asia. This led to expeditions into present-day Xinjiang, marking the first major conflict between Han Chinese and Central Asian ethnic groups. Defeated tribes were relocated within the Great Wall and gradually assimilated into the Han culture.

During this time, the historian Sima Qian wrote Records of the Grand Historian (史记 Shiji), using a literary style to document decades of large-scale warfare between the Han and Central Asian tribes, with vivid descriptions of emperors, chieftains, ministers, envoys, generals, and the vast desert landscapes. This period marked the first integration of two major ethnic groups in Chinese history.

After the fall of the Han dynasty, China experienced a brief period of turmoil and division, which led to the Three Kingdoms period. Following reunification, there was even greater fragmentation, which lasted for nearly 300 years. During this time, northern ethnic groups continuously migrated into China, and for the first time, central governments were established by non-Han ethnic groups.

These rulers adopted Han administrative systems, writing, customs and ethical values. Over time, they even lost their original languages and traditions and blended into the Han ethnicity, which is one of the great mysteries of Chinese history — whenever minority groups conquered China, they ultimately assimilated into Chinese civilisation and became part of the broader Chinese identity.

The Tang dynasty established the basic pattern for the territorial expansion of the Chinese empire. The Han Chinese themselves did not expand militarily; instead, ethnic minorities took control of China and further extended its borders through military campaigns.

The Tang dynasty: a dynasty led by a minority

The Tang dynasty is a classic example. It was one of China’s most powerful dynasties, and its founding emperor (Emperor Gaozu of Tang, birth name Li Yuan) was descended from the Xianbei people, an ethnic group of the Eurasian steppe, known for their blond hair, blue eyes and high-bridged noses — features associated with the European race. This made the Tang dynasty particularly unique, as the royal lineage contained what would be considered Caucasian ancestry today. (NB: The debate over the Xianbei’s ethnic origin is a longstanding and politically charged issue. Some assert that the Xianbei were a non-Mongolian Indo-European people with white skin and often blond or reddish hair, while others argue for their Mongolian or Tungusic roots.)

Unlike the agrarian traditions of the Han Chinese, Emperor Taizong of Tang (birth name Li Shimin) was skilled in horseback riding and archery, and was renowned for his valour and military prowess. The capital, Chang’an, was a vibrant, cosmopolitan metropolis where nightlife flourished, and women wore relatively revealing clothing — an image reminiscent of Rome or Babylon as depicted by Western historians. Such excess and indulgence stood in stark contrast to strict Confucian values of ethics and propriety.

Given their minority heritage, the Tang rulers saw their military campaigns in Central Asia as extensions of tribal conflicts rather than foreign conquests; Emperor Taizong was even recognised as the paramount ruler by many Central Asian tribes. During his reign, he sent the Buddhist monk Xuanzang on a journey to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures, furthering the cultural and religious exchanges between China, Central Asia, and India. At its peak, the Tang empire encompassed Xinjiang, Tibet, northern Vietnam, Mongolia, Manchuria, and northern Korea. In regions where the Tang dynasty overlapped with neighbouring ethnic groups, new mixed-ethnicity populations emerged.

The Tang dynasty established the basic pattern for the territorial expansion of the Chinese empire. The Han Chinese themselves did not expand militarily; instead, ethnic minorities took control of China and further extended its borders through military campaigns. Eventually, these conquerors assimilated into the Han community, forming a new China with mixed ethnicities.

Assimilation and integration

The Song and Ming dynasties were purely Han-led, while the Yuan and Qing dynasties were ruled by the Mongols and Manchus respectively. The Manchu military expansion significantly shaped China’s territorial boundaries, incorporating Manchuria, Inner and Outer Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Taiwan into the empire. While the Han people were forced to adopt Manchu customs, such as wearing queues and donning Manchu clothing, the Manchu emperors also embraced their role as rulers of China. After a few hundred years of Qing rule, usage of the Manchu language and writing system declined as the Manchus sought to assimilate into the Han population.

The Hollywood movie The Last Emperor inadvertently captured the self-identification of the Manchu emperor as a Chinese ruler. On the other hand, Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist Revolution initially called for the overthrow of Manchu rule by the Han people. However, after the revolution’s success, the movement quickly shifted to the idea of the five major ethnic groups — Han, Manchu, Mongol, Hui, and Tibetan — forming the Chinese nation (中华民族 zhonghua minzu). This is also the foundation of China’s ethnic policies today.

Beyond the five major ethnic groups, there are many other smaller ethnic communities that often overlap with neighbouring countries. There are ethnic overlaps with East Asia; for example, some members of the Korean ethnic group live in China’s northeast region, while Inner Mongolia and Mongolia share the same ethnic roots. There are also links to Central Asia — Xinjiang’s Kazakhs are ethnically linked to Kazakhstan, and the Uighurs are also part of the Turkic ethnic family, like the Turks.

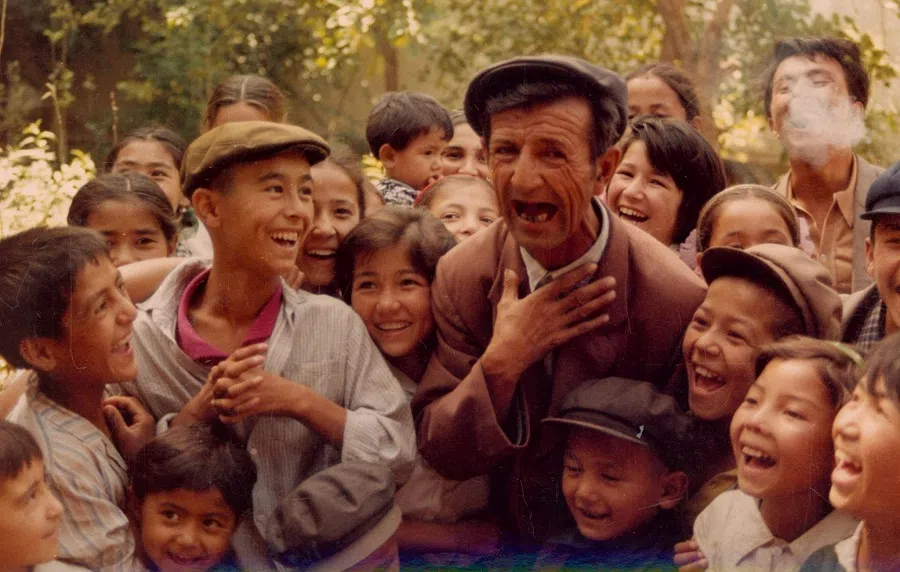

Ethnic overlaps even extend to Southeast Asia — Yunnan’s Dai people are related to the Thai, Guangxi’s Zhuang people share ancestry with the Vietnamese, and the Miao people are found in northern Vietnam and Thailand. These ethnic minorities have languages and customs similar to those of their counterparts in neighbouring countries, fostering close cultural ties. In recent years, migration and cross-border interactions between both sides have become increasingly common. Such interactions are relatively easy because there are no language or cultural barriers.

As for the respective legends of their ancestral origins, their colourful and diverse clothing, and unique flavours of their cuisine, these aspects of minority culture not only attract large numbers of tourists but also enrich the breadth and depth of Chinese culture.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)