Can the Philippines as ASEAN chair 2026 navigate South China Sea tensions?

As the Philippines assumes the ASEAN chair in 2026, can it balance China relations, US alliances and regional trust-building through trade, green energy and security cooperation? Researcher Muhammad Faizal gives his take.

In October 2025, Philippine officials voiced opposition to the installation of floating barriers by China at Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea. The Philippines sees this as another illegal action under the 2016 ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration on the maritime dispute between China and the Philippines, while China could argue that this action demonstrates its restraint as it counters activities that challenge its maritime rights and territorial sovereignty.

Philippines gears up for 2026 ASEAN chairmanship

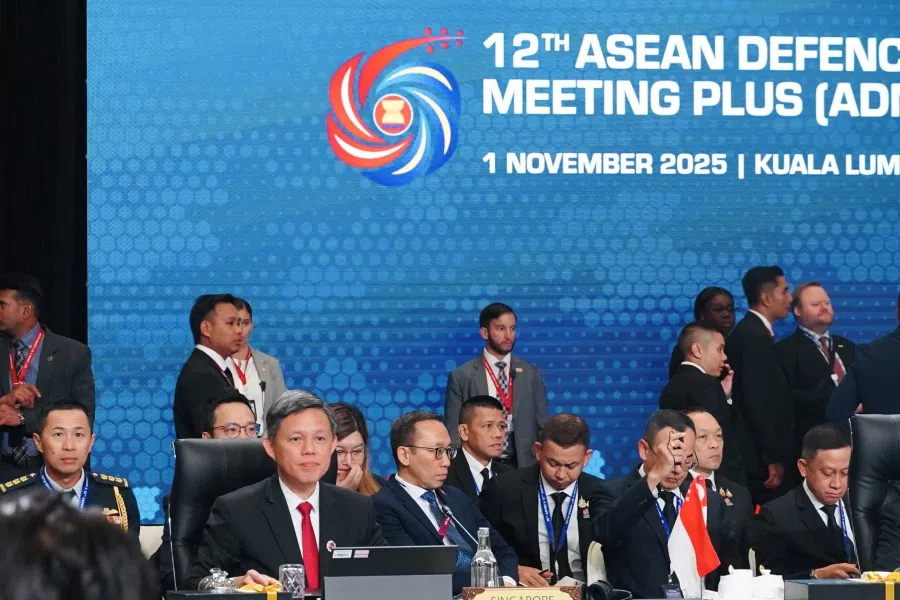

At a meeting on 1 November 2025 on the sidelines of the 12th ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus (ADMM Plus), the defence ministers of Australia, Japan, the US and the Philippines (also known as the SQUAD) met to regularise the Japan-Australia-Philippines-US Defense Ministers’ Meeting. This effort institutionalises the minilateral arrangement between the ASEAN chair in 2026 — the Philippines -– and three non-ASEAN powers to counter China at the East China Sea and South China Sea.

On the sidelines of the 19th ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM) on 31 October, the Philippines reportedly discussed with the newest member of ASEAN — Timor Leste — about formalising a defence cooperation arrangement.

This arrangement could be symbolic and a capacity-building initiative to assist the newest ASEAN member, quite similar to the defence cooperation agreement that Malaysia signed with Timor-Leste after the latter officially became the 11th ASEAN member state. Some experts could argue that the Philippines is courting Timor-Leste as another regional partner, which is also a coastal state, to counter China with regard to the South China Sea.

These recent developments indicate that the South China Sea remains the most complex and irreconcilable geopolitical issue for Southeast Asia and will likely further dominate ASEAN’s political-security agenda for 2026. Other ASEAN member states would likely watch this space closely as it could impact their bilateral relations with China and the US, and their future chairmanship of ASEAN, especially Singapore in 2027.

The region now has to work with a more powerful China as well as an ASEAN chair that diplomatically promotes ASEAN processes but, in practice, takes a stronger stance on the South China Sea issue through non-ASEAN security partnerships.

When the Philippines, under President Duterte, last held the ASEAN chair in 2017, it pushed for a softer stance on the South China Sea issue. Nonetheless, it made progress in the more attainable defence diplomacy goals. These conditions may have facilitated Singapore’s chairmanship of ASEAN in 2018, when it achieved several milestones in regional security.

The regional strategic environment has evolved since then. The region now has to work with a more powerful China as well as an ASEAN chair that diplomatically promotes ASEAN processes but, in practice, takes a stronger stance on the South China Sea issue through non-ASEAN security partnerships.

South China Sea issue remains irreconcilable

The crux of the issue still revolves around competing visions and perspectives on maritime order, which are intertwined with the strategic interests — such as sovereignty, national pride, economic goals and geopolitical power — of the contesting parties.

From China’s perspective, what Western experts regard as “unprofessional” or “unsafe” manoeuvres occur because foreign military vessels and aircraft enter what China considers its sovereign airspace and territorial waters. And from the Western perspective, when the Philippines and non-ASEAN powers conduct exercises or operations there, they regard it as legitimate and in line with international navigation rights.

During the 12th ADMM Plus Meeting, the US pushed for ASEAN countries to take a stronger approach to counter China in the South China Sea in line with the US perspective of maritime order. More importantly, the Philippines continues to play a major role in US foreign policy and defence strategy regarding the South China Sea.

A key question is how the Philippines’ strategic interests would interplay with ASEAN’s goal of enhancing trust and confidence between its member states and dialogue partners, and resolving intra-regional issues...

On the sidelines of the 12th ADMM Plus Meeting, the US and the Philippines announced that they have formed a joint task force to increase military readiness and re-establish deterrence in the South China Sea. Unlike the previous taskforce Ayungin, which focused on a specific geographic spot, this new taskforce aims to align the US operationally with the Philippines’ Comprehensive Archipelagic Defence Concept.

Seeking middle ground or drama

The year 2026 will be significant for ASEAN regional security as the Philippines, a US treaty ally, takes over as ASEAN’s chair. At the 20th East Asia Summit in November 2025, Philippine President Marcos made pointed comments regarding China and the South China Sea. A key question is how the Philippines’ strategic interests would interplay with ASEAN’s goal of enhancing trust and confidence between its member states and dialogue partners, and resolving intra-regional issues such as the Myanmar crisis and Cambodia-Thailand border conflict.

Looking ahead to 2026, parties involved in the South China Sea issue may have to address a fundamental conceptual challenge if they wish to explore pragmatic pathways to manage political tensions as the issue remains irreconcilable. This challenge is about finding some alignment or middle ground in competing perspectives of the maritime order.

The Code of Conduct (COC) should serve as a bridge between competing perspectives of the maritime order. The potential for this bridge still exists because all parties share a similar interest in peacefully managing maritime disputes. However, the conclusion of the COC negotiations will likely remain elusive. If parties cannot acknowledge that what one side perceives as territorial violations, the other side considers legitimate navigation rights — and vice versa — then it would be difficult for the COC to bridge differences in perspectives.

The region and China need to work together to survive in a changing world order, one in which the US, as described by economics professor Jeffrey Sachs, is the “most destabilising force”.

Nonetheless, it is crucial to ensure that South China Sea tensions do not significantly impact the overall relations between China and Southeast Asia. The region and China need to work together to survive in a changing world order, one in which the US, as described by economics professor Jeffrey Sachs, is the “most destabilising force”.

Pragmatic cooperation to ease South China Sea tensions

Parties to the South China Sea issue should continue to develop or maintain confidence-building measures such as real-time communication hotlines between coast guards and navies, advance notification of military exercises, and joint search-and-rescue programmes. In relation to this, it was positive news when US War Secretary Pete Hegseth and Chinese Defence Minister Dong Jun, during the 12th ADMM Plus Meeting, discussed reopening the military hotline between the US and China.

But there should also be other areas of cooperation to build trust and confidence, thereby mitigating the impact of persistent tensions in the South China Sea.

For example, the upgraded ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) should be used to strengthen supply chain connectivity and reduce trade barriers to offset the impact of US tariffs. In the green economy, China has the potential to share technical expertise with ASEAN member states to support the ASEAN Power Grid initiative, which is vital to sustainable development in the region.

Concrete cooperation in these areas could help build trust and confidence, as they align with the developmental priorities of the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP), and the trust and confidence generated may help manage complex issues, such as the South China Sea.

Ultimately, a more flexible, pragmatic and diverse approach to trust and confidence-building is crucial to regional security as the resolution of the South China Sea issue remains elusive.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)