China’s ‘new multilateralism’: A rival to the US-led order?

China is asserting itself in global governance through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and alternative multilateral initiatives, combining consultation, soft laws and high standards to challenge the US-led order, says Chinese academic Gu Bin.

With the dawn of Trump 2.0, the world order, which had largely been working well for 80 years, is hastening its pace of collapse. What will the new world order look like, how will the transition unfold and will there even be a third world war in the interim?

The decay of the present-day world order is due to two main factors: the US’s abuse of hegemony and the Global South’s underrepresentation in global affairs.

Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs” and “no going back” approach to getting Greenland have opened up a Pandora’s box of achieving whatever monetary, economic and geopolitical interests he wants in the name of safeguarding national security. As a result, the global trade order has been “jolted”, quoting World Trade Organization (WTO) director-general Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s diplomatic language.

... the essence of multilateralism is framed as “decided by all, built by all, and shared by all”. This means, if we all chip in and add wood to the bonfire, the flames will be much higher, as an old Chinese saying goes.

China’s Global Governance Initiative more relevant than ever

The slogan “No taxation without representation” captures the grievances that triggered the American War of Independence in the 18th century. A similarly unfair phenomenon — “contribution without representation”, has existed for a long time in the international community. Yet emerging economies and developing nations are only seeking evolution, not revolution.

In the midst of a “rupture”, quoting Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney at Davos, the Global Governance Initiative (GGI) marks China’s latest, most potent action of leadership in stabilising world situations.

As proposed by President Xi Jinping at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit last year, GGI upholds multilateralism as the pathway to global governance. To elaborate, first, multilateralism is placed at the very core of the existing world order; it must be preserved, rather than eroded.

Second, the essence of multilateralism is framed as “decided by all, built by all, and shared by all”. It means, if we all chip in and add wood to the bonfire, the flames will be much higher, as an old Chinese saying goes.

Third, in parallel, all practices of unilateralism and discrimination must be avoided and rejected. This clearly pinpoints and targets the main cause of uncertainty troubling us all today.

In its cultural genes, China is not a missionary society; it chooses to influence others by inducing respect rather than by conversion...

‘New multilateralism’ under China’s leadership

For the purpose of reviving an effective and efficient multilateralism under GGI, I will humbly present a new theory — “new multilateralism” (NM), or Chinese multilateralism under China’s leadership.

NM features “heritage and innovation”, as it builds upon American multilateralism (AM), the traditional world order led by the US since World War II, while drawing on a few new case studies, namely the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), two of China’s global initiatives.

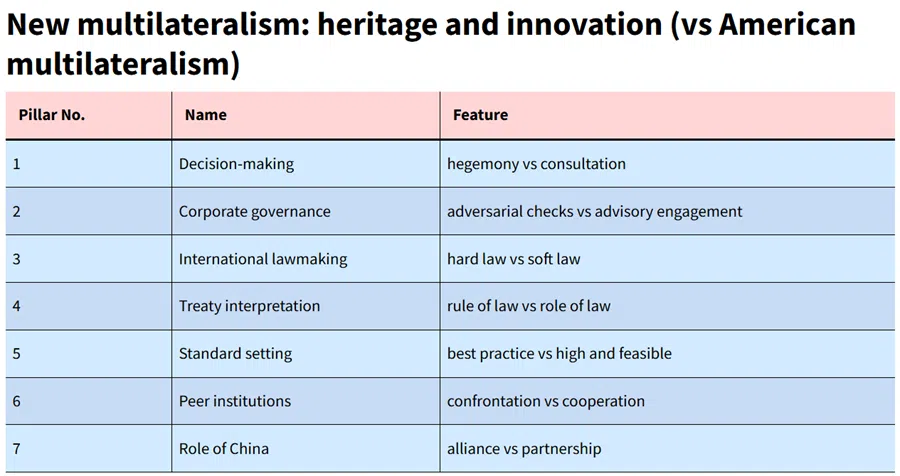

NM builds itself upon seven interdependent pillars.

The first pillar is decision-making, featuring hegemony versus consultation. In contrast to AM where the US acts a hegemon, NM prioritises broad-based consultation in decision-making.

China holds a veto power in the AIIB, as the US does in Bretton Woods institutions. But holding a veto power is one thing; to abuse it is another. In its cultural genes, China is not a missionary society; it chooses to influence others by inducing respect rather than by conversion, contrasting with a hegemon’s mentality to impose its will on others.

The second pillar is corporate governance, featuring adversarial checks versus advisory engagement. While AM follows the Western style of adversarial checks, NM leans towards the Oriental wisdom of advisory engagement.

The legal corpus of BRI is mainly made up of soft laws, alongside treaties and other hard laws. Notwithstanding being vague, loose and flexible, this feature contributes to the quick expansion of the largest-ever international development platform in the 21st century.

Soft vs hard laws

The AIIB has a built-in oversight mechanism “to ensure proper checks and balances” between its non-resident board and management, where the degree of propriety lies along a spectrum, depending on the Bank’s Asian genes. This model features unity and collegiality, and promotes connectivity and collaboration. As the world is witnessing a surge in bullying, this spirit of reconciliation and harmony is all the more essential.

The third pillar is international lawmaking, featuring hard laws versus soft laws. As opposed to AM, which enjoys a strong tradition of formal and hard international lawmaking, NM cherishes informal and soft international lawmaking.

The legal corpus of BRI is mainly made up of soft laws, alongside treaties and other hard laws. Notwithstanding being vague, loose and flexible, this feature contributes to the quick expansion of the largest-ever international development platform in the 21st century. Indeed, soft international lawmaking matters and works amid our tumultuous times.

The fourth pillar is treaty interpretation, featuring rule of law versus role of law. While AM upholds the rule of law from an angle of formality, NM examines the role of law from a teleological perspective.

Teleological interpretation enables an international organisation, like a living tree, to grow and expand within its natural limits, which are embedded in the purposive clause in the organisation’s charter. The teleological approach justifies the AIIB investing in BRI projects, as well as taking up policy-based loans, by flexibly interpreting its laws.

The fifth pillar is standard setting, featuring best international practice versus high and feasible standards. In contrast to AM’s way of upholding best practices, which implies the stigma of one size fits all, NM embraces balanced, high and feasible standards.

High standards are integral in the operations of the AIIB, which has instituted environmental, social, and governance standards (ESG) both in text and in practice. At the same time, the AIIB also prioritises the interests of borrowing countries, and takes into account their local conditions.

China is with everybody and against nobody, which contrasts against US-branded hegemony — “either with us or against us”.

The sixth pillar is peer institutions, featuring confrontation versus cooperation. According to NM, forging a cooperative external relationship, particularly with those established ones, is key to the success of a newcomer.

The AIIB has forged a pragmatic, collaborative relationship with the World Bank and other peer institutions, by signing memorandums of understanding and co-financing projects. This approach has helped the AIIB to make rapid progress in building up its reputation and capacity building.

China prizes continuous self-improvement and partnership-building

The seventh pillar is the role of China, featuring alliance versus partnership. The Chinese dream is two-pronged, consisting of “rejuvenating the nation” and “building a community of shared future for mankind”.

To make this happen, China tends to concentrate on continuous self-improvement and partnership-building, while avoiding making enemies. China is with everybody and against nobody, which contrasts against US-branded hegemony — “either with us or against us”.

... China is showing more confidence, with concrete steps, in helping to shape the new world order...

China’s leadership in global governance is demonstrated in reforming US-led traditional institutions, as well as in initiating the BRI and the AIIB. In the WTO, for example, China initiated an investment facilitation agreement, and alongside Europe, an alternative appellate arbitration mechanism. China also pledged not to seek new special treatment in the WTO, while generously funding capacity building programmes for the Global South in e-commerce, where China’s own development experience excels.

Thus, China is showing more confidence, with concrete steps, in helping to shape the new world order, positively echoing then US Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick’s call decades ago for China to become a “responsible stakeholder”.