How China is shaping India without confronting it

Amid China and India’s seeming rapprochement, China’s structural penetration into South Asia has become increasingly visible this year. Beijing is no longer nibbling at the region’s edges, but laying a wedge, says academic Hao Nan.

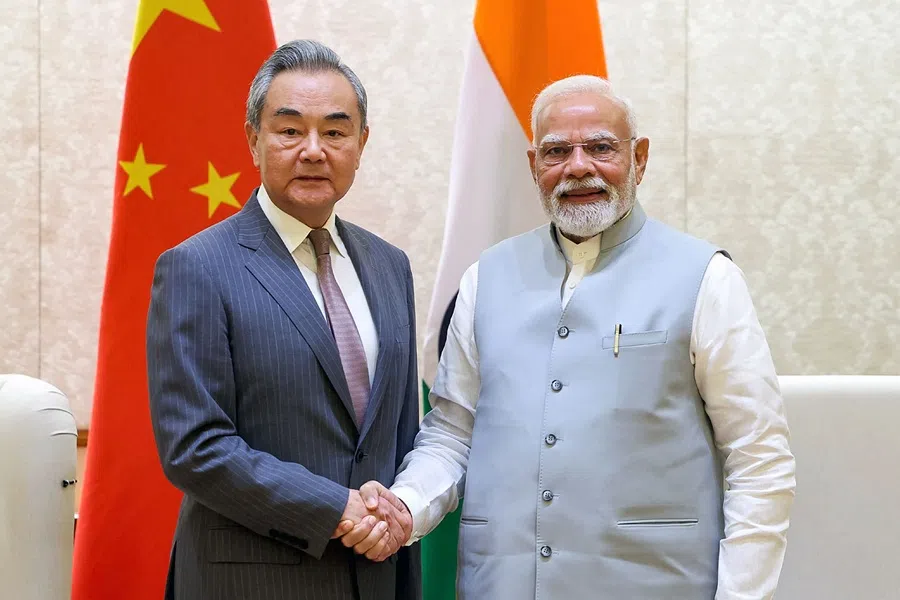

On 18-19 August, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi concluded his visit to India after a three-year hiatus, holding meetings with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, national security adviser Ajit Doval and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The visit resulted in a ten-point consensus to resume negotiations on the long-stalled border dispute, along with a separate ten-point roadmap to revive broader bilateral ties.

As is typical in Chinese diplomatic practice, this fruitful visit is likely to pave the way for a bilateral summit between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Modi on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in China at the end of the month — an occasion that could formally signal a rapprochement between the two countries.

China’s growing structural influence in South Asia — via minilaterals, corridors and defence ties — has raised the cost of Indian defiance.

New Delhi feels the squeeze

While much of the global media frames New Delhi’s hedging toward China in light of President Trump’s tariff threats — especially over purchases of Russian oil, which India’s external affairs ministry has called unjustified and unreasonable — it tends to overlook China’s structural penetration into South Asia, which has become increasingly visible this year.

Beijing is no longer nibbling at the region’s edges — it is laying a wedge. From Kunming’s new vice-foreign-ministerial track with Pakistan and Bangladesh, to the SCO’s high-tempo pre-summit ministerial convenings, China has used its SCO chair year to normalise its convening role while quietly tightening physical and military linkages around India.

Add to that the spectre of President Trump’s clear preference for US-Russia-China trilaterals, which contrasts with the Biden administration’s emphasis on multilateral cooperation and engaging a wider network of partners and allies. As a result, New Delhi faces a dual squeeze — both structural and economic — that will temper its room for manoeuvre at the SCO.

China’s growing structural influence in South Asia — via minilaterals, corridors and defence ties — has raised the cost of Indian defiance. If that hard architecture is coupled with the looming threat of an additional 25% US tariff by 27 August, on top of the existing 25%, India may become more dependent on Chinese-led forums for risk management and crisis de-escalation. This would give Beijing greater leverage to “discipline” India’s actions at the 2025 SCO summit and, by extension, influence New Delhi’s agenda when it chairs BRICS in 2026.

Web of minilaterals

First, the minilateral web. Beijing has spent years building small-group formats that socialise its convening power around India’s periphery, with Pakistan sitting in the centre of these efforts.

A notable example was the informal meeting in May 2025, which helped catalyse the restoration of ambassador-level ties between Islamabad and Kabul. Most recently, following his visit to India, Wang Yi travelled directly to Islamabad on 20 August for the official sixth round of the dialogue.

This new trilateral arrangement explicitly extends the China-Pakistan strategic web along India’s eastern flank.

In April, Pakistan and Bangladesh — two historical rivals — resumed foreign minister-level talks after a 15-year hiatus, aiming to warm bilateral ties and ease people-to-people exchanges. Building on this rapprochement, China in June inaugurated a China-Pakistan-Bangladesh vice-foreign minister mechanism in Kunming, with agreements on trilateral cooperation across various sectors and the formation of working groups to implement them. This new trilateral arrangement explicitly extends the China-Pakistan strategic web along India’s eastern flank.

Encircling corridors

Next, corridors and concrete. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) remains the flagship initiative, and is now explicitly being discussed within the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan trilateral framework for potential extension into Afghanistan — linking Gwadar’s access to the Arabian Sea with key nodes in Afghanistan and Central Asia.

Beyond that, China is reinforcing Indian Ocean Rim footholds with ports, bridges and industrial zones, while development loans to Sri Lanka and the Maldives consolidate a manufacturing and logistics spine along critical sea lanes.

Perhaps most striking is the proposed US$167 billion hydropower megadam project in Tibet, near the border with northeast India. Designed to generate nearly 300 billion kilowatt-hours of clean, renewable, zero-carbon electricity annually — enough to meet the yearly needs of over 300 million people — it has the potential to supply cheap, large-scale power to Bhutan, Bangladesh and Nepal. In doing so, it could transform upstream capacity into downstream dependency. The cumulative effect is one of geographic encirclement through connectivity.

Upping defence ties

Finally, defence ties. China has supplied around 81% of Pakistan’s weapons over the past five years. During the spring 2025 crisis, Pakistan fielded Chinese J-10C fighters with PL-15 beyond-visual-range missiles — their first recorded wartime use — cementing the credibility of Chinese kit against India’s Western-sourced front line.

At sea, successive Hangor-class submarines deepen Pakistan’s undersea deterrent and China’s footprint in the northern Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives are edging toward Chinese arms and training to balance India’s traditional influence. This is what structural penetration looks like when the chips are down.

China is positioned to turn India’s re-engagement into incremental “rules of the road”. These include clearer crisis hotlines, tighter agenda discipline on counter-terrorism and connectivity working groups that privilege Chinese standards.

SCO: Beijing’s new rules

Against that backdrop, China’s SCO chairmanship has been purposeful, not ornamental.

The SCO is under significant stress test this year, especially with India’s distancing role. Beijing is rehabilitating the SCO as a crisis management hub while keeping core principles — sovereignty and non-interference — front and centre.

The May India-Pakistan flare-up forced the bloc to navigate an intra-group standoff in which New Delhi withdrew from the joint communique at the last minute over the language on terrorism. The June Israel-Iran crisis pulled the SCO toward Middle East sensitivities, and India publicly distanced itself from a joint statement condemning Israel’s strike on Iran, a fellow SCO member.

Meanwhile, Russia’s war in Ukraine kept Indian energy purchases in the spotlight and exposed New Delhi to US tariff pressure — an external lever that makes multilateral cover more valuable to India, not less. When Washington rattles the tariff sabre, the near-term incentive for New Delhi is to show up in venues where China can offer procedural off-ramps and regional stabilisers.

That is precisely Beijing’s strategic opening. With Sino-Russian alignment reaffirmed at the 8 May Xi-Putin summit — including pledges to deepen coordination across sectors and multilateral forums like the SCO and BRICS — and a new China–Central Asia treaty signed in June to channel BRI rail, energy and border projects into SCO-aligned pathways, China is positioned to turn India’s re-engagement into incremental “rules of the road”. These include clearer crisis hotlines, tighter agenda discipline on counter-terrorism and connectivity working groups that privilege Chinese standards. None of this demands a grand bargain — only that India accept the chair’s pace and vocabulary.

Beijing’s target is not India’s sovereignty but its operating tempo and vocabulary inside multilateral settings.

Conditioning India’s bandwidth and choices

Where do Trump’s tariff threats fit? They tighten the vise.

India wants strategic autonomy, but it also wants growth. If the US link becomes more contingent and costly, New Delhi will hedge harder inside Eurasian formats where China controls the gavel this year and holds outsized sway next year.

The immediate impact is likely to be modest but meaningful: fewer public theatrics and more procedural compromises at the upcoming SCO leaders’ summit — such as resumed flights, eased visas and trade facilitation.

This would set the tone for India’s 2026 BRICS chairmanship, during which New Delhi may find itself spending more effort on risk-managing China than actively balancing it. A smooth handover to China in 2027 would offer a symbolic moment of unity — just as Trump nears the end of his single second term. Beijing does not need to “win” BRICS; it simply needs to condition India’s bandwidth and choices.

Critics will object that India will never submit to “disciplining”, that its hedging is by design, and its democracy is allergic to external pressure. True, there will be no capitulation or formalised hierarchy. And yes, the SCO remains a consensus-bound club, ill-suited to sharp institutional leaps. But those constraints are China’s friend.

Beijing’s target is not India’s sovereignty but its operating tempo and vocabulary inside multilateral settings. If New Delhi accepts China’s procedural lead to keep the tariff wolf at bay and stabilise its periphery, that is influence enough — and a template for how India’s 2026 BRICS chairmanship may, in practice, be shaped by the same structural pressures.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)