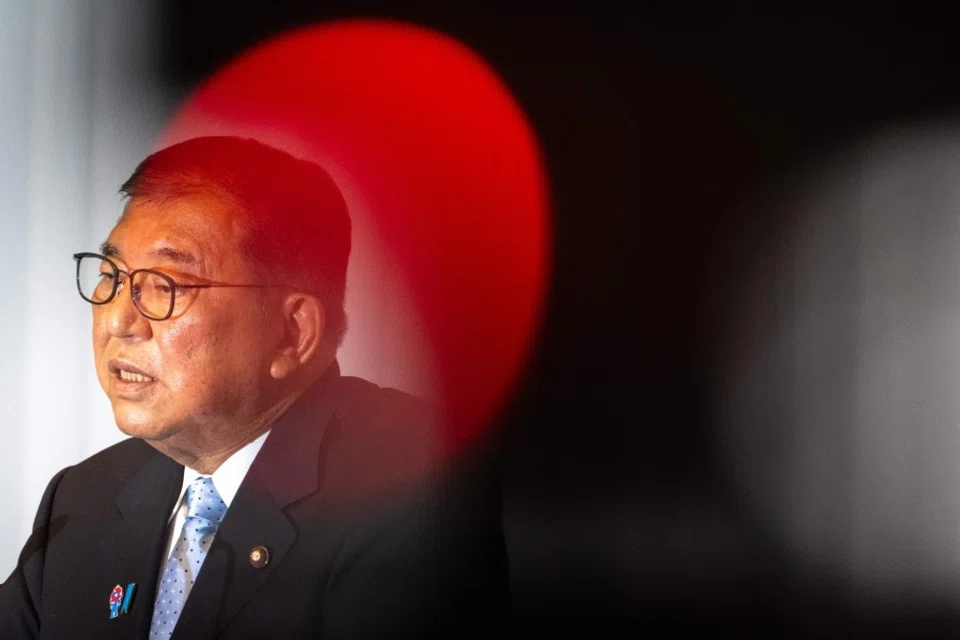

Ishiba: The ‘flawed’ leader Japan clings to

Following Shigeru Ishiba’s failure to win a majority in the House of Councillors election in July, his future is in doubt as to how long he can hold on, amid bumps with tariff negotiations with the US, as well as domestic challenges such as handling Japan’s WWII legacy. Academic Toh Lam Seng analyses the situation.

Following the 21 July setback in the House of Councillors election, in which the ruling coalition of Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Komeito failed to secure half of the seats, public attention has turned to whether weakened Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba will resign, or when he might be forced to do so.

The reasoning is straightforward: as the head of the ruling party, Ishiba has now led the LDP to two consecutive defeats (the other being last October’s House of Representatives election), resulting in the party becoming a minority in both chambers of the Diet. Under such circumstances, he cannot evade political responsibility and is expected to resign.

As soon as the election results were announced, calls erupted within the LDP to “topple Ishiba”. Leading the charge was former Prime Minister Taro Aso, the head of the only remaining intact major faction in the party; closely following him was former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, the ex-leader of the Kishida faction. In addition, other senior figures — such as Yoshihide Suga, who, despite lacking power within the party, once served as an interim prime minister — joined in both openly and behind the scenes, directly or indirectly mounting pressure for his resignation.

Meanwhile, younger ambitious party members long eyeing the party presidency have also been manoeuvring in the background. In short, Ishiba’s political fate is no longer in his own hands. His resignation is only a matter of time.

In other words, Ishiba does not dare hope to cling to the premiership indefinitely; he only seeks to extend his tenure by invoking the need to confront a “national crisis”.

The ‘excuse’ of tariff negotiations

In response, Ishiba could do little more than repeatedly apologise, while stressing that he must continue governing with Komeito due to pressing national issues such as “tariff negotiations”.

The implication is that, as US President Donald Trump is aggressively wielding tariffs as a weapon and Japan faces what is portrayed as a “national crisis”, it would be unwise for the power centre in Nagatacho (where the prime minister’s office is located) to undergo a leadership change, lest it weaken Japan’s bargaining position with the White House.

In other words, Ishiba does not dare hope to cling to the premiership indefinitely; he only seeks to extend his tenure by invoking the need to confront a “national crisis”.

Whether the White House had seen through Ishiba’s plight, or because Ishiba himself was eager to clinch a tariff deal in order to “stay alive”, just as he was besieged on all sides, Trump swiftly announced on 22 July that the US and Japan had reached a “massive” trade agreement.

According to Japanese media reports, Tokyo highlighted that Japanese exports to the US would be subject to a 15% tariff, lower than the White House’s earlier demand of 25%. At the same time, Japan agreed to invest US$550 billion in the US, creating hundreds of thousands of jobs.

Not a gift from Trump

When it came to Japan’s promised investment, details were not fully disclosed, and from the outset, Tokyo and Washington were making contradictory statements. Trump even went so far as to preemptively declare that the US would pocket 90% of the profits. This could hardly be described as a negotiating achievement or victory for Ishiba.

Still, the fact that the White House, which had previously threatened a 25% tariff, agreed to lower the figure to 15% was regarded — however sceptically — as a testament to Ishiba’s negotiating skills. From this angle, the “massive” trade agreement appeared to be a gift Trump had given to Ishiba, whose administration was on the brink of collapse. Yet this so-called “gift” and “achievement”, awaiting further confirmation, was soon undercut by an executive order issued by the Trump administration.

In the end, Japanese politicians accustomed to yielding to the US had no choice but to swallow the bitter pill in silence, including “policy expert” Ishiba.

It turns out that to Washington, the so-called 15% import tariff applied only to Japanese products that had previously faced tariffs below 15%. For goods already taxed at more than 15%, the order mandated not that tariffs remain at their existing level, but that an additional 15% duty be imposed on top of the original rate. The gap between the US and Japanese interpretations was therefore enormous.

Ishiba’s government and its negotiators immediately protested, claiming Washington’s statement contradicted the consensus reached during talks. But the so-called “consensus” as understood by the Japanese side had never been committed to any signed document. Faced with this reality, the Ishiba administration could do little beyond grumbling and pledging to continue tough negotiations.

Why did Japan’s famously meticulous bureaucrats fail to insist on a written agreement for such a critical deal in which they supposedly held the upper hand? It is puzzling. In the end, Japanese politicians accustomed to yielding to the US had no choice but to swallow the bitter pill in silence, including “policy expert” Ishiba. From this perspective, Ishiba’s “national crisis” card — played on the grounds of confronting US tariff negotiations — was not enough to sustain his dream of “staying alive”.

Perhaps the most unexpected, or even heartwarming, moment for him came on 25 July. Just as he was cornered on all sides and his ouster seemed inevitable, crowds of ordinary citizens gathered outside the Prime Minister’s Office holding banners and chanting slogans such as “Go Ishiba!” and “Ishiba, don’t resign!”

In consideration of “choosing the lesser evil”, many citizens opposed Ishiba’s resignation.

Ishiba: relatively measured and pragmatic

According to reports, the reason why these citizens rallied to stop Ishiba from resigning was less about endorsing or praising his domestic and foreign policies, and more about their fear that, if he stepped down, the post would be taken over by Sanae Takaichi, a female politician described as a “hawk among hawks”, who pursues an even more hardline agenda.

Takaichi, a graduate of the conservative training ground Matsushita Institute of Government and Management, is a frequent visitor to the Yasukuni Shrine. She shares the same views on security and Japan’s neighbours as the late former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and is known for her blunt speech and open defence of prewar historical narratives. Should she come to power, combined with the rise of small far-right parties such as the Sanseito, Japan’s political trajectory would indeed be cause for concern.

By comparison, although Ishiba has long been seen as a right-wing figure with a strong focus on military and defence issues — rising as a leader of the so-called “new defence tribe”, which advocates strengthening Japan’s military and revising its pacifist constitution — he is viewed as relatively measured and pragmatic.

Japan’s constitutionalists embrace a pragmatic conservative

In consideration of “choosing the lesser evil”, many citizens opposed Ishiba’s resignation. Reportedly, some of those who joined this movement were Social Democrats and Japanese Communists committed to “defending the pacifist constitution”. The scene inevitably prompts reflection on the decline of Japan’s once-powerful pro-constitution movement.

Moreover, perhaps because Ishiba is eloquent and skilled at self-packaging, some have even overlooked his fundamentally conservative “new defence tribe” background and instead see him as a rare, principled voice within the LDP, hoping this self-proclaimed “disciple of Kakuei Tanaka” would contribute to improving Sino-Japanese relations.

But a closer look at statements from “liberal” scholars who support Ishiba tells a more complex story. Among them are intellectuals who, during Japan’s political realignment in the 1990s, were strong advocates for introducing the single-seat constituency system — a change that ultimately weakened the Japan Socialist Party (JSP). These scholars also criticised the JSP’s pacifist interpretation of the constitution and backed the Democratic Party’s more “realistic” approach to national security and foreign policy.

From this perspective, support for Ishiba reflects both the anxious but helpless choice of some pro-constitution citizens under the current political climate, and the convergence of their aims with proponents of “realistic” security and diplomacy. For the latter, it is easy to see why they view Ishiba as a like-minded figure and have endorsed his domestic and foreign policies since he took office.

Delivering an ‘Ishiba Statement’ about the war?

Another noteworthy development is that this year marks the 80th anniversary of Japan’s defeat in World War II on 15 August. Since former Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama delivered the “Murayama Statement” in 1995, it has become customary for Japanese leaders to issue commemorative statements at such anniversaries.

True to his reputation for parsing words carefully, Ishiba was eager to follow in the footsteps of Murayama (1995), Junichiro Koizumi (2005), and Shinzo Abe (2015) by delivering an “Ishiba Statement” (2025) approved by the Cabinet and read personally by him.

... he did not say a single word about Japan’s responsibility as an aggressor.

Because Ishiba had once remarked that the “end of the war” should more accurately be called the “day of defeat”, and had frankly acknowledged Japan’s fundamental responsibility for starting the war, some media outlets optimistically expected the “Ishiba Statement” to break through the confines of previous commemorations, offering more direct language of reflection and apology.

According to reports, Ishiba even set up a panel of experts in April to study the causes of Japan’s “reckless war”, so that it might draw lessons from this tragic experience and reaffirm its resolve to build a peaceful nation. The panel was scheduled to present its final report to the Prime Minister in August, as an important reference for his statement.

Yet despite such expectations, there were no signs that Ishiba would actually go beyond precedent with a bold expression of his views on the “day of defeat”. And even though Ishiba only appeared to be striking the posture of wanting to establish a “peaceful state”, many hawks within the LDP voiced strong opposition.

In their view, Prime Minister Abe had already, in 2015, reaffirmed Japan’s “deep remorse and apology” for its “acts of aggression and colonial rule”, and declared the matter of apology settled once and for all. Therefore, they argued, there was no need for Ishiba to issue yet another statement.

In response, Ishiba had earlier said that while he would not be able to deliver a Cabinet-approved “Ishiba Statement”, he still hoped to release a “personal statement” at an appropriate time. Some commentators and media sympathetic to Ishiba’s “pragmatic” line sought to amplify the possible differences between such a “personal statement” and the LDP hawks’ rhetoric, interpreting them as a deeper divergence in historical consciousness between two camps within the party.

But when one looks at what was laid out in Ishiba’s speech on 15 August at the National Memorial Service for the War Dead, apart from declaring, “We must never again repeat the horrors of war. We must never again lose our way. We must now take deeply into our hearts once again our remorse and also the lessons learned from that war,” he did not say a single word about Japan’s responsibility as an aggressor.

... interpreting Ishiba’s “soul-searching” on historical issues as making him an “unsullied stream” within the conservative camp — is to fall into the trap set by certain Japanese media narratives.

On the same day, while Ishiba did not visit the Yasukuni Shrine like Shinjiro Koizumi Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and son of former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi) and former LDP Minister of Economic Security Sanae Takaichi, he nevertheless, through his office, personally paid for a tamagushi offering (ritual fee) to the “war gods” as a token of reverence.

This suggests that taking the prime minister’s words too literally — and interpreting Ishiba’s “soul-searching” on historical issues as making him an “unsullied stream” within the conservative camp — is to fall into the trap set by certain Japanese media narratives.

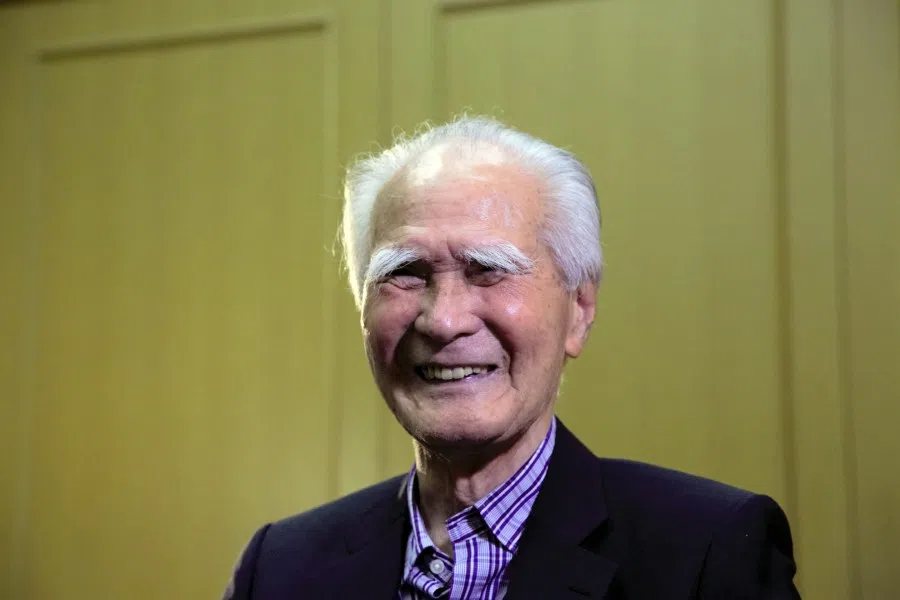

Japan’s distorted political stage

Junichiro Koizumi, who visited the controversial Yasukuni Shrine six times in six years, was once mocked by political strategist Ichiro Ozawa — who helped reshape Japanese politics and push it toward conservatism — as a “right-winger without real conviction”, emphasising political posturing over genuine belief.

... the sight of pro-constitution citizens backing an “astute” prime minister who supports rearmament and faster militarisation — just to keep Takaichi or Shinjiro Koizumi from leading — reveals the distorted state of Japanese politics...

Similarly, Ishiba — who prides himself on “policy talk” and strategic thinking — dismisses younger politicians like “Koizumi Junior” (Shinjiro) and Takaichi as immature, “reckless right-wingers”. A sober analysis, however, shows that the difference between Ishiba and the latter two, whether in historical outlook or security policy, is merely the pot calling the kettle black.

Thus, the sight of pro-constitution citizens backing an “astute” prime minister who supports rearmament and faster militarisation — just to keep Takaichi or Shinjiro Koizumi from leading — reveals the distorted state of Japanese politics and would likely leave Ishiba feeling both amused and frustrated.

The chaotic drama of Japanese politics, it seems, will continue to unfold.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “石破政权残局与日本走向”.