Japan says no, again: Ishiba’s defence gamble

Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba prioritises security and diplomacy, proposing an Asian NATO to counter the “China threat” and seeking an equal US-Japan alliance. This bold stance, echoing Japan’s past “Say No” era, faces regional pushback and tests his strategic manoeuvring, says academic Toh Lam Seng.

As widely anticipated, Shigeru Ishiba won the runoff vote in Japan’s National Diet due to the fragmented opposition and became Japan’s 103rd prime minister. This was despite the setback he suffered in his gambit in the lower house snap election that resulted in the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) losing more than 50 seats and its parliamentary majority as LDP’s loyal partner Komeito also suffered severe losses.

Yet it is common knowledge that this minority government is constantly at risk of facing a no-confidence motion from the opposition parties. With little support within the LDP, Ishiba has no shortage of rivals eyeing his position. Despite claiming to be familiar with many areas of policies, he is unlikely to be able to fully implement his brand of domestic and external policies. Indeed, he will have to make some choices and compromises.

Vision for security and rhetoric on diplomacy

Among the many domestic and external challenges, Ishiba is likely to prioritise what he considers to be his strengths, namely his vision for security and rhetoric on diplomacy.

Ishiba’s vision for security came to light in September when he proposed an Asian NATO during the LDP leadership election. He declared that Japan should station troops in US military bases in Guam to forge an equal alliance with the US.

His rhetoric on diplomacy was made known when he decided to contest for LDP leadership as he referred to Taiwan as a “country” and led a delegation of more than ten lawmakers to Taiwan.

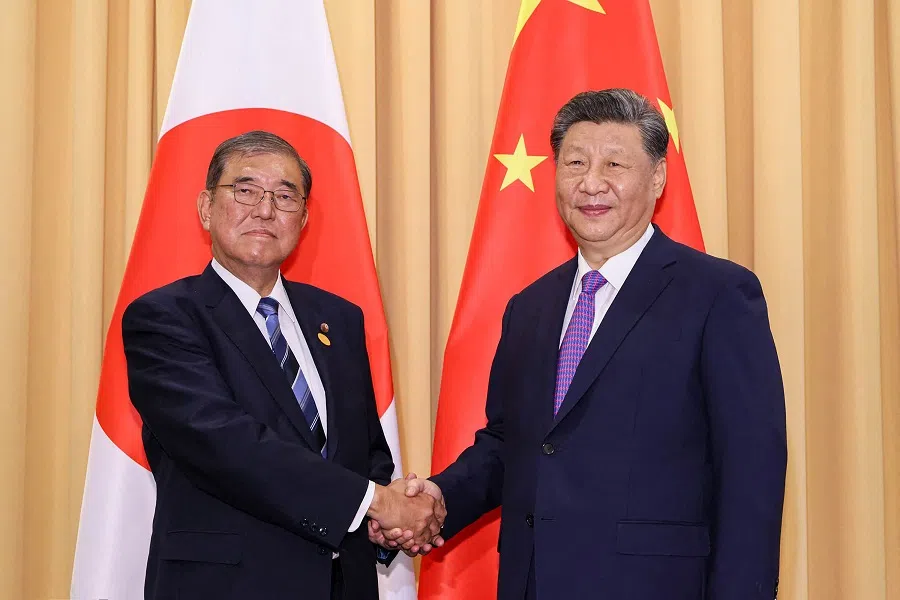

However, after taking office as prime minister, he has repeatedly claimed to have been mentored by former Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei, who visited China and normalised China-Japan relations in 1972, and professed a strong desire to enhance China-Japan bilateral exchange and dialogue.

ASEAN media and in particular The Jakarta Post clearly stated that ASEAN needs Japan as a reliable trade and economic partner and not as an ally who would only escalate regional tensions.

Far from a brilliant rhetoric on diplomacy

Despite initially challenging Beijing’s red lines with bold rhetoric, he later expressed a desire for closer relations, highlighting Tanaka’s ties with China. This inconsistent approach falls short of effective diplomacy.

This approach bears striking resemblance to that of former Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda, now leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party. In 2011, Noda claimed to be “the first product” of China-Japan exchange (as he was one of 3,000 Japanese youths invited to China in 1984 during President Hu Yaobang’s era) yet ordered the purchase of the Senkaku Islands (known in China as Diaoyu Island and its affiliated islands) in 2012.

Ishiba’s vision for security, particularly his idea of an Asian NATO, has made its rounds and drawn strong reactions. Couched as addressing the “China threat” and aimed at advocating for an equal Japan-US alliance to jointly govern Asia-Pacific, this idea invited immediate opposition from the US and India. Moreover, ASEAN media and in particular The Jakarta Post clearly stated that ASEAN needs Japan as a reliable trade and economic partner and not as an ally who would only escalate regional tensions.

As the backlash to Ishiba’s idea exceeded Tokyo’s expectations, his trusted foreign minister, Takeshi Iwaya, scrambled to mitigate the fallout, saying that the idea would require mid- to long-term discussions. Ishiba himself backed down as well and avoided any mention of it at the ASEAN Summit in Laos in October.

Firmly bound to US-Japan Security Treaty

A scrutiny of the history of post-war Japan-US relations and the changes to the rhetoric on the Japan-US alliance reveals that Ishiba’s vision for security is not unprecedented among the Japanese conservative elites. It is a matter of who articulates it, whether directly or indirectly, as well as when and where.

Simply put, since Japan’s unconditional surrender in August 1945 and the enforcement of the Treaty of San Francisco in April 1952, Japan was occupied solely by the US in the name of the Allied Forces. General Douglas MacArthur, known as the “white-faced emperor”, called all the shots during this period. The Class A war criminals released in December 1947, including Japanese politicians such as Nobusuke Kishi who later became Japan’s prime minister, had no choice but to obey.

The Treaty of San Francisco was signed on 8 September 1951 and became effective on 28 April 1952, marking the end of the US occupation of Japan. Many Japanese consider 28 April as Japan’s independence day. However, on 28 April 1952, the US-Japan Security Treaty that was also signed on 8 September 1951, came into effect. In other words, the post-war “independent” Japan was immediately and firmly bound to the US-Japan Security Treaty.

Viewed from outside, the US-Japan Security Treaty framework is evidently an alliance, despite the asymmetry of status and lack of equality between the two nations. However, due to domestic and external circumstances, Japan officially denied that this was an alliance and, in particular, a military alliance in the initial three decades for three reasons.

The hallmark of this approach is the priority in economic diplomacy and remaining submissive, at least outwardly, towards the US.

First, Japan’s Peace Constitution renounces Japan’s sovereign right to wage war and to maintain military forces. Second, scarred by war, the Japanese public was vehemently anti-war and anti-nuclear, as well as particularly sensitive to the term “alliance” and especially “military alliance”. Third, as memories of Japanese military atrocities lingered in Asia, Japan had to hide behind the US in its southward expansion of economic influence. In this context, the “supervision of Japan by the US” facilitated post-war Japanese economic recovery, while a Japan-US alliance, especially a military one, was counterproductive to Japan’s rejuvenation.

Hence, the political elites of post-war Japan often tacitly observed this sole strategy as the only way to survive, by biding their time and aligning with the US.

The ‘security-economy-prosperity rhetoric’

This is precisely the reason why post-war Japan, led by bureaucrats-turned-politicians from the mainstream conservative LDP factions including former Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru, has focused on economic and not military development. The hallmark of this approach is the priority in economic diplomacy and remaining submissive, at least outwardly, towards the US. These Japanese politicians believed that the US-Japan Security Treaty was the basis for Japan’s post-war prosperity and success, and the “security-economy-prosperity rhetoric” encapsulated this approach.

Against this backdrop, despite his strong interest in military development, in December 1967 then Prime Minister Eisaku Sato declared in the National Diet the Three Non-Nuclear Principles, of not possessing, not producing and not permitting the introduction of nuclear weapons. Ironically, just as Sato was eagerly anticipating his Nobel Peace Prize in 1974, a bombshell from Washington embarrassed him. It was reported that former US Rear Admiral Eugene LaRocque had testified before the US Congress that US ships had not offloaded their onboard nuclear weapons when entering Japanese ports.

This testimony directly contradicted Japan’s long-held official assertion of banning entry of ships armed with nuclear weapons, and undermined the Sato government’s Three Non-Nuclear Principles. Amid public outcry and strong reaction from the opposition and the media, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs had to repeatedly state that it believed that the report was untrue, dismissing LaRocque’s statements as purely his personal opinions, and urged the US government to clarify its position.

These incidents demonstrate that 36 years after World War II, the term “alliance” continued to evoke in the Japanese public painful memories of the alliance of the Axis Powers comprising Japan, Germany and Italy...

Taboo of the term ‘alliance’

Although the US-Japan Security Treaty effectively instituted a hierarchical “military alliance”, there was a dichotomy of domestic opinion in Japan that represented divergence in two completely different choices and views on Japan’s future. The Japanese government had to deny the existence of a military alliance. Even the term “alliance” was regarded as sensitive.

This situation persisted into the early 1980s. In May 1981, then Foreign Minister Masayoshi Ito was fiercely criticised by the opposition and the media after agreeing to include the term “alliance” in a Japan-US joint statement. Furthermore, former US Ambassador to Japan Edwin Reischauer had publicly acknowledged that US nuclear-armed naval ships had frequently docked at Japanese ports. This forced the Japanese government, led by then Prime Minister Zenko Suzuki, to emphasise that its non-nuclear policies remained unchanged. After Ito was forced to resign, Suzuki appointed Sunao Sonoda as foreign minister.

These incidents demonstrate that 36 years after World War II, the term “alliance” continued to evoke in the Japanese public painful memories of the alliance of the Axis Powers comprising Japan, Germany and Italy, which initiated the war that resulted in their devastating defeat.

With this renewed debate over the term “alliance” within the LDP, Japan’s long-standing official narratives or smokescreens of “restraint in military expansion” and “sole focus on economic growth”, repeatedly played up by Western media, were beginning to unravel.

Unveiling the Yoshida school of thought

Notably, even as mainstream conservatives such as Shigeru Yoshida championed Japan’s focus on economic over military development, Japanese officials and hawkish LDP members had advocated constitutional amendment and twisted the interpretation of the Constitution by re-interpreting its limits. Former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, nicknamed the “Showa Era Monster”, was a prominent advocate of constitutional amendment.

After former Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, regarded as the “Heisei Era Monster”, came to power in the early 1980s, he openly proposed the “final settlement of post-war politics” and aimed to dismantle the various post-war taboos. In January 1983, during his visit to the US, Nakasone publicly emphasised the relationship of alliance between Japan and the US, that the two nations “share a common destiny that binds them together”. He further pledged to make Japan an “unsinkable aircraft carrier”. Despite these encountering vehement domestic criticisms, the idea of a Japan-US alliance subsequently ceased to be taboo.

In the early 1990s, politician Ichiro Ozawa, often referred to as the “Shadow Shogun” as he was instrumental in Japan’s political re-organisation, proposed the concept of Japan as a “normal nation”. In his book Blueprint For A New Japan, Ozawa directly argued that the Yoshida Doctrine or the Yoshida school of thought did not truly oppose re-armament but that Japan was then constrained by economic, social and ideological conditions.

He is also attempting to use the “China threat” to demand that the White House relinquishes partial military authority in the Asia-Pacific, to enable Japan to shoulder the duties as an ally and share the defence responsibilities. This demonstrates extraordinary chutzpah on the part of Ishiba.

Ozawa pointed out that according to Yoshida’s writings, he believed that if independent Japan, an economically, technologically and academically advanced nation, continued to depend on other nations for self-defence, then it would essentially remain as a nation that resembles a unicycle.

Balancing acts of manoeuvre

At the height of Japan’s economic might, right-wing politicians such as Shintaro Ishihara stridently declared through the title of his book, asserting The Japan That Can Say No. With Japan’s newfound strength, the debate raged over whether it should strive to become the world’s number one or settle for second after the US. Calls surfaced for an equal Japan-US military alliance, and the conservatives fuelled waves of anti-Americanism.

However, it should be noted that the demands for a more equal alliance with the US are different from the public opposition to the US-Japan Security Treaty framework. After Japan’s economic bubble burst, anti-Americanism largely faded and was replaced by deference to the US, exemplified by leaders such as Shinzo Abe and Fumio Kishida, who renewed Japan’s pro-US diplomatic approach and followed the US’s lead.

Japan has stagnated for two to three decades, and Ishiba is now reviving the call that “Japan Can Say No”. He is also attempting to use the “China threat” to demand that the White House relinquishes partial military authority in the Asia-Pacific, to enable Japan to shoulder the duties as an ally and share the defence responsibilities. This demonstrates extraordinary chutzpah on the part of Ishiba.

Let us observe the champion of new national defence, strategist and tactician Prime Minister Ishiba in his balancing acts of manoeuvre. It will certainly be challenging to navigate these treacherous waters onboard this Ishiba vessel that can potentially run aground at any time.