My memories of Jiang Zemin: Editor-in-chief, Chinese Media Group

From her time on the political desk then as Zaobao's Hong Kong correspondent and Beijing correspondent, Lee Huay Leng, editor-in-chief of SPH Chinese Media Group, recalls her impressions of the late former Chinese President Jiang Zemin. Jiang represented the ideas and workings of an era in Chinese politics, and played a great role in shaping China's domestic policies and international diplomacy.

When I had a meal with a returning colleague from Beijing recently, I dredged up some of my memories as an old-time journalist as we spoke of the late former Chinese President Jiang Zemin. My colleague said she had no such collective memories.

Actually, she does. After some years, when she talks to younger colleagues about the news events and personalities she has come across in her work, she would feel the link between her work and the time period. Then, she might realise that aside from collective memories, how one chooses memories and what to remember has to do with personal experience.

Getting a sense of Jiang through reporting

When Lianhe Zaobao reported Jiang's demise, there was a photo of Jiang visiting Singapore in 1994. That year, I was a rookie sports reporter who was not too attuned to current affairs. In 1995, Jiang's name came up more often in my work. In late January, he spoke of an eight-point proposition on China's reunification, what the Hong Kong media called "Jiang's Eight Points". These included welcoming Taiwanese leaders to mainland China, while China was also willing to accept invitations to go to Taiwan.

In the middle of the year, Taiwanese President Lee Teng-hui visited the US and cross-strait relations were tense as the People's Liberation Army (PLA) conducted military exercises and missiles flew over the Taiwan Strait. At the time, after six months on the political desk, I went to Bandar Sri Begawan in Brunei to cover the ASEAN Foreign Ministers' Meeting. Amid this Taiwan Strait crisis, I waited for Chinese Foreign Minister Qian Qichen and US Secretary of State Warren Christopher to speak to each other.

What stood out was that Jiang highlighted this was China's "family matter", and Singapore had no role to play. I began to feel the heft of this Chinese leader.

Gradually, Jiang's name went from something in the back of my mind to being more directly related to my work. In 1996, I was working on the transcript of Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew's interview with NBC's Tom Brokaw. Lee revealed that he made a suggestion to Jiang to form an airline and shipping line with Singapore, mainland China and Taiwan as shareholders, indicating that Singapore was willing to bridge the cross-strait gap. But Lee quoted Jiang as saying that this was a "Chinese family matter" for Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau. Lee told Brokaw: "After that brush-off, I think, I have no role."

In fact, on another occasion before this, I had already heard Lee himself tell grassroots leaders this anecdote. What stood out was that Jiang highlighted this was China's "family matter", and Singapore had no role to play. I began to feel the heft of this Chinese leader.

In December 1997, for the first time, I went as a journalist with Lee's delegation to Vietnam and China. As I was not very experienced, I was walking on eggshells when I took on this assignment - we journalists were even more on edge after Lee lectured local officials at the Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP). Subsequently in Beijing, Lee wanted to raise the issues with the SIP with Jiang. We did not go to the venue for the talks, but waited at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse. I did not know Jiang's style, but we were all familiar with Lee's straightforward speech, and so we were anxious: would the two leaders fall out with each other?

After Lee spoke with Jiang and attended a dinner by Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji, he returned to the State Guesthouse and took questions from the journalists. He was at ease, and quoted Jiang in Chinese saying that "this problem can be resolved". He gave us a detailed account of the talk with Jiang on the SIP's problems and Jiang's responses. The most important result was that Jiang confirmed that the SIP was a top priority in China, and this was the point that everyone later highlighted. But from Lee's narration, I got a sense of Jiang's temperament, and of the relationship between the two leaders.

... Jiang's remarks also demonstrated his visionary thinking and geniality as a Chinese leader.

Reanalysis with time

Now rereading the articles I wrote back then, I have a different understanding as well. News reports of leaders' bilateral meetings rarely go into the details or openly discuss differences over collaborative projects. But back then, Jiang particularly explained to Lee that he had been busy with numerous major events such as Deng Xiaoping's passing at the beginning of the year, Hong Kong's handover, the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) 15th Party Congress and his visit to the US, and so he was unaware of the challenges that the SIP was facing.

Before Lee's visit to China, some materials had already been sent to Jiang, who directly sought to understand the situation from Vice-Premier Li Lanqing who was in charge of the project, instead of merely reading official reports. Jiang not only took Lee's "complaint" seriously, but also thanked Lee for his frankness, because he himself advocated such dialogues between top leaders. Jiang also reiterated that in building friendships, trust was paramount.

At the same time, Jiang's remarks also demonstrated his visionary thinking and geniality as a Chinese leader. SIP's shareholding adjustment was completed in 2001. At a ceremony to mark the achievements of SIP's seven years of development hosted by Lee Kuan Yew and Li Lanqing, Jiang had specially flown in from Beijing to Suzhou after making a transfer in Shanghai. He affirmed Lee's contributions to SIP's development and also expressed his hopes to strengthen SIP's competitiveness in international business. With this, the differences over the industrial park were resolved.

Interestingly, I later heard that when the pair spoke informally, Jiang often used English while the latter used Mandarin. During their formal meetings, they usually spoke for over an hour, exchanging views on the international situation.

Although an "elderly" was lecturing the journalists, the entire atmosphere was still relaxed, and laughter was occasionally heard.

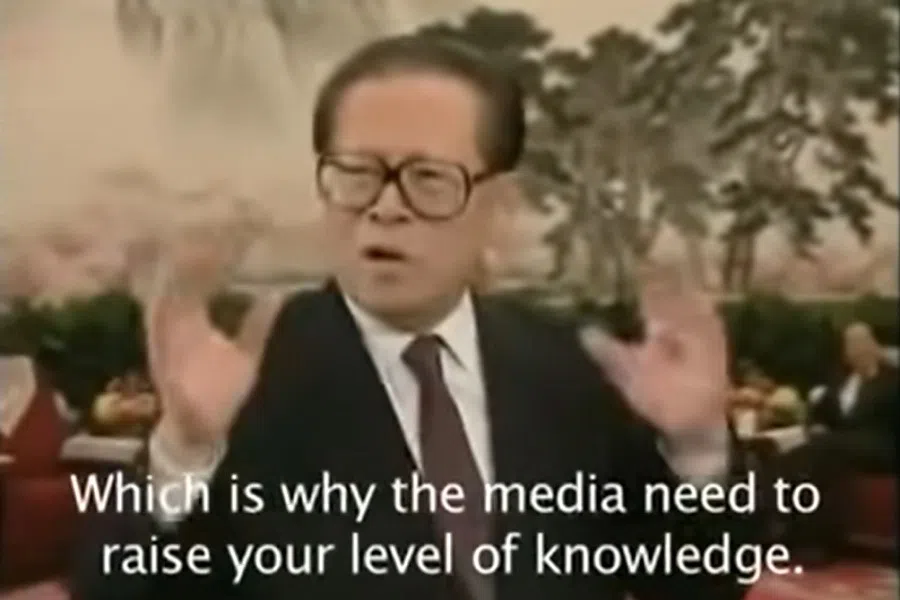

When I became Zaobao's Hong Kong correspondent in 1999, "Jiang Zemin" took up an even larger proportion of my work. One day at the Hong Kong bureau, Hong Kong Cable Television aired a clip of Hong Kong journalists asking if Jiang would "endorse" then-Hong Kong Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa for a second term.

Speaking to the camera, Jiang responded in a lively mix of Mandarin, English and Cantonese, and tried advising the Hong Kong journalists to step up their game in a rather earnest and well-meaning way. Later on, he even said "silence is golden" (闷声发大财), but he couldn't bear not to respond to their questions after seeing their enthusiasm. Throughout the footage, the Hong Kong journalists were relentless while Qian Qichen, Tung and other officials sat looking on with polite smiles.

Although an "elderly" was lecturing the journalists, the entire atmosphere was still relaxed, and laughter was occasionally heard. In our society, such incidents would count as being quite disrespectful. But the fact that it happened in Beijing was not so much due to Hong Kong journalists advocating freedom of the press but Jiang's openness, tolerance, and willingness to interact with Hong Kong journalists in this manner.

Ending of an era

When I was based in Hong Kong, my superiors often sent me to Beijing to cover the major meetings there. In 2002, following Jiang's delivery of the CCP's 16th Party Congress report and delegates discussing it in breakout groups, reporters were even allowed to sit in at some of the discussions. My seniors told me that this had been the practice since the 15th Party Congress. Back then, we didn't think of it as a big deal. But my younger colleagues were all envious when they heard that it was even possible to door-stop delegates on their way to the toilet at that time. We all felt that it was a sign of openness in Jiang's era, and also a true mark of confidence.

For a massive country like China which has gone through numerous ups and downs, it was no mean feat that such a complete and peaceful leadership succession had taken place.

At the closing ceremony of the 16th Party Congress, Jiang relinquished his general secretary position to fourth-generation leader Hu Jintao. Two years later, I became Zaobao's Beijing correspondent. When I was working in the office on a Sunday afternoon, I saw the news that Jiang had stepped down as chairman of the Central Military Commission. I had a sense of exhilaration.

For a massive country like China which has gone through numerous ups and downs, it was no mean feat that such a complete and peaceful leadership succession had taken place. After being elected as general secretary at the 16th Party Congress, Hu said that the old comrades who stepped down from their positions showed the broad-mindedness and moral integrity of Communist Party members, and his words set me thinking.

After Jiang passed away, I pored over relevant news or videos of his passing before going to bed every night. As I watched CCP leaders from Jiang's era or the era after him attending his memorial service and paying their respects, it stirred up my emotions.

We race against time every day but one day when an important figure suddenly passes away, we are reminded that this truly is the end of an era. That was a different era with its own set of experiences, different personalities and different interpersonal relations. Every era will come to an end - apart from honouring an era that has passed, we must also remember to keep up with the times.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "我所记得的江泽民".

![[Big read] China’s 10 trillion RMB debt clean-up falls short](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/d08cfc72b13782693c25f2fcbf886fa7673723efca260881e7086211b082e66c)