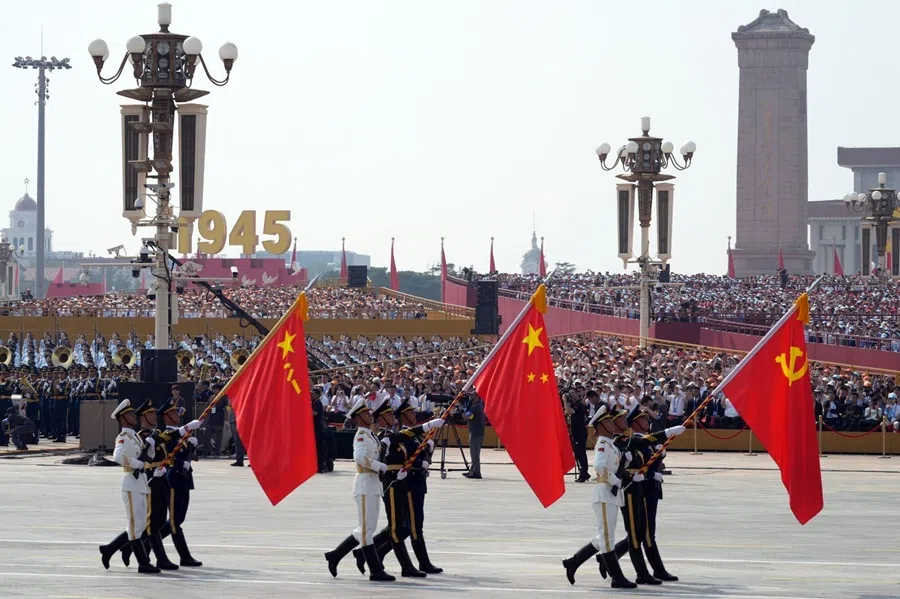

What 3 million suggestions reveal about China’s evolving governance under Xi Jinping

Can public opinion truly shape policy in China — or is it merely a tool to bolster the Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy? Researcher Genevieve Donnellon-May explores the issue.

As China prepares its 15th Five-Year Plan (2026–2030), the blueprint is being shaped by the country’s most pressing challenges, from slowing growth and industrial transformation to national security, foreign trade and demographic shifts. To inform this process, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has turned to digital platforms to solicit public input.

Mammoth project

Earlier this year, state media launched a national campaign to gather public input and feedback for the plan. From 20 May to 20 June, an online consultation invited citizens and industries nationwide to submit their suggestions. Chinese media reported more than 3.11 million submissions, underscoring the growing scale of public engagement in policy formation.

To guide responses, proposals submitted through these platforms are capped at 4,000 words, with an email address from the State Council Information Office made available for longer submissions. The Beijing Review noted that the collected opinions and suggestions will be summarised and provided as reference for decision-making by the central leadership.

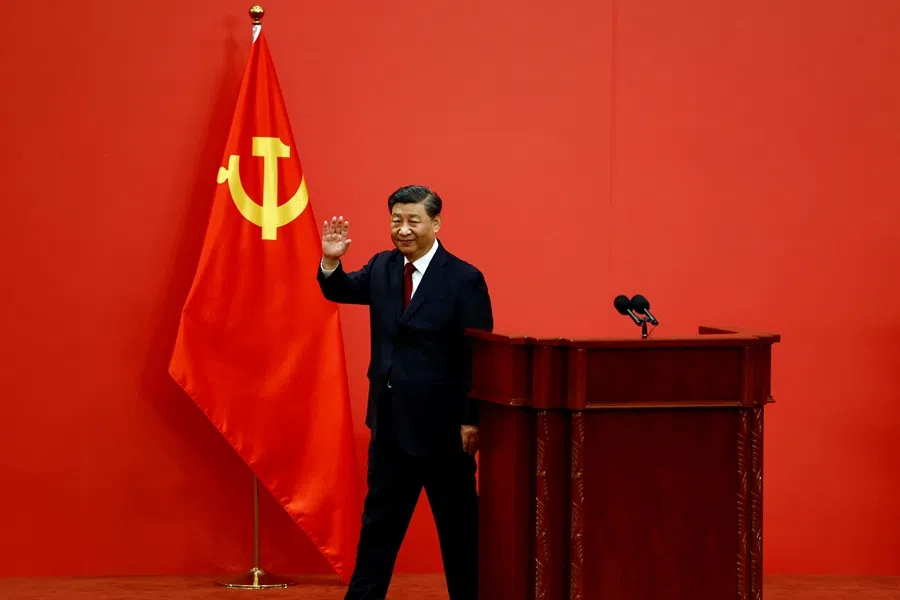

President Xi Jinping highlighted the importance of this exercise, calling for suggestions to be “studied, absorbed and utilised” so that the plan reflects the “voice of the people”.

While this initiative projects inclusivity, it also raises questions about transparency and influence.

The consultation on the 15th Five-Year Plan is the largest to date, surpassing the roughly one million suggestions received during the 14th Five-Year Plan drafting in 2020.

Chinese policymaking: millions shape Five-Year Plan?

China first used online platforms to solicit public opinion on its five-year plan in 2020, during the drafting period of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25). This reflects the CCP’s emphasis on “whole-process people’s democracy”.

These exercises serve dual functions: projecting an image of participatory governance while providing the state with valuable insights into public sentiment on key issues. Their growing scale reflects increased digital outreach via platforms such as People’s Daily, Xinhua and the Study to Strengthen the Nation (学习强国) app. The latter reported 345 million registered users and an average of 700 million daily visits in 2024.

The consultation on the 15th Five-Year Plan is the largest to date, surpassing the roughly one million suggestions received during the 14th Five-Year Plan drafting in 2020. By embedding consultation links and QR codes across widely used digital platforms, authorities sought to maximise reach and encourage mass participation.

Beyond long-term planning, the government has increasingly invited public comment on specific pieces of legislation. In recent years, this has included, for instance, a draft revision to the Civil Aviation Law and the release of a draft of the Private Economy Promotion Law for consultation. Such initiatives suggest a gradual institutionalisation of feedback mechanisms in areas directly affecting citizens’ daily lives.

For the 15th Five-Year Plan, feedback submissions were collected through official online platforms operated by state-run media, including People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency and affiliated portals. Citizens were encouraged to provide input on topics ranging from economic development and technological innovation to environmental protection, social welfare, and cultural policies.

The party retains full discretion to adopt, adapt or ignore feedback, highlighting the gap between the appearance of openness and the reality of centralised authority.

Legitimacy and limits of transparency

Public consultations in China primarily serve to legitimise CCP governance. By soliciting input, the party signals responsiveness and reinforces its “people-centred governance” narrative, consolidating political authority while projecting an image of participatory decision-making.

Participation, however, is carefully bounded. Citizens can submit suggestions, but there are no mechanisms to challenge final decisions or hold authorities accountable. In this light, it suggests that public consultations are a sounding board rather than a decision-making tool.

Although submissions cover a wide range of topics — from economic growth to defence and technology — the lack of transparency in evaluation, selection and integration processes limits insight into their actual influence. The party retains full discretion to adopt, adapt or ignore feedback, highlighting the gap between the appearance of openness and the reality of centralised authority.

... citizens could resort to self-censorship — either out of political caution to avoid repercussions or through internalised restraint shaped by social and political norms.

This opacity may constrain accountability. Without a formal feedback loop, citizens may remain uncertain whether their contributions have any impact. In some cases, citizens could resort to self-censorship — either out of political caution to avoid repercussions or through internalised restraint shaped by social and political norms. In more extreme cases, this gap between perception and reality may weaken trust over time if citizens increasingly view consultations as symbolic rather than substantive or practical instruments of governance.

Beijing’s feedback trap?

At the same time, the scale of the consultation — over three million submissions — may create structural challenges. Selection criteria remain undisclosed, raising the risk of misalignment between citizen expectations and policy outcomes.

Social media dynamics further shape visibility: monitoring of platforms like Weibo and WeChat can amplify supportive voices while marginalising dissent, reinforcing pre-existing policy goals rather than fostering genuine deliberation.

Individual contributions highlight the breadth of participation for the 15th Five-Year Plan. Chinese media showcased different responses For instance, one user, Li, expressed concern about the use of pesticides on crops and advocated for the establishment of a food traceability system. Such comments not only provide a channel for citizen input but also demonstrate how consultations are framed as vehicles for public accountability and responsiveness. Meanwhile, user Yang recommended more subsidy policies and mechanisms, like income tax deductions for raising children

While policy may appear responsive to citizen input, in practice, it is shaped by managed narratives and political imperatives.

Implications for international business community

China’s public consultation process introduces significant uncertainty for foreign stakeholders. While policy may appear responsive to citizen input, in practice, it is shaped by managed narratives and political imperatives.

The Five-Year Plan sets the direction for industrial policy, regulatory frameworks and market priorities, influencing sectors from energy and technology to healthcare and logistics. When public sentiment emphasises domestic stability and resource security, foreign firms may face tighter controls, additional compliance requirements, or sudden regulatory shifts.

The opacity of decision-making compounds these risks: without clarity on how public input informs policy, companies struggle to anticipate regulatory changes, understand the rationale behind reforms or plan investments strategically.

For instance, adjustments in environmental regulation, data governance or industrial standards may reflect both public opinion and party priorities, leaving firms with limited ability and time to prepare.

Instruments of statecraft

Geoeconomically, these consultations also function as instruments of statecraft. By framing domestic policies as reflecting popular will, the CCP signals both internal legitimacy and the capacity to align economic strategy with national security goals.

For foreign observers and investors, the message is clear: while public opinion is solicited, central political priorities remain decisive, and foreign enterprises must navigate a policy landscape shaped as much by political imperatives as by popular sentiment.

China’s online consultation for the 15th Five-Year Plan illustrates both the promise and the paradox of participatory governance under the CCP. On one hand, it reflects an evolving governance style that leverages digital tools to gauge sentiment, pre-empt discontent, and strengthen legitimacy. On the other, it highlights enduring limits — citizen voices are invited but filtered, and real decision-making authority remains centralised. Meanwhile, for the international business community, the consultation introduces both opportunities and risks.