[Big read] After the fire: Can Hong Kong still be Hong Kong?

As part of Lianhe Zaobao’s “Seeing the New Hong Kong” series, marking five years since the enactment of Hong Kong’s national security law, correspondent Lim Zhan Ting and associate China news editor Fok Yit Wai speak with Hong Kong residents to understand how they are adapting to their new normal following the 2019 anti-extradition bill movement.

Under the blazing sun in June, Molly Yeung, a 20-year-old student at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, took a ferry to the rustic outlying island of Peng Chau. She bought a piece of cha guo (茶粿, tea cake) for HK$8 (US$1.02) at an old shop, and quietly savoured the treat in an old street corner.

Cha guo is a traditional Hong Kong pastry made with glutinous rice wrapped around a filling, but it has become a rarity in the city. Yeung told Lianhe Zaobao that in recent years, mainland Chinese shops have mushroomed in the Tseung Kwan O area where she resides in Sai Kung, and local-flavoured shops have become few and far between.

Yeung made a special trip to Peng Chau, hoping to reconnect with local culture and support the small shops on the island. “After all, it’s been very tough for them to survive these past few years,” she said.

She expressed, “I want to fall in love with Hong Kong again.”

Preserving old Hong Kong

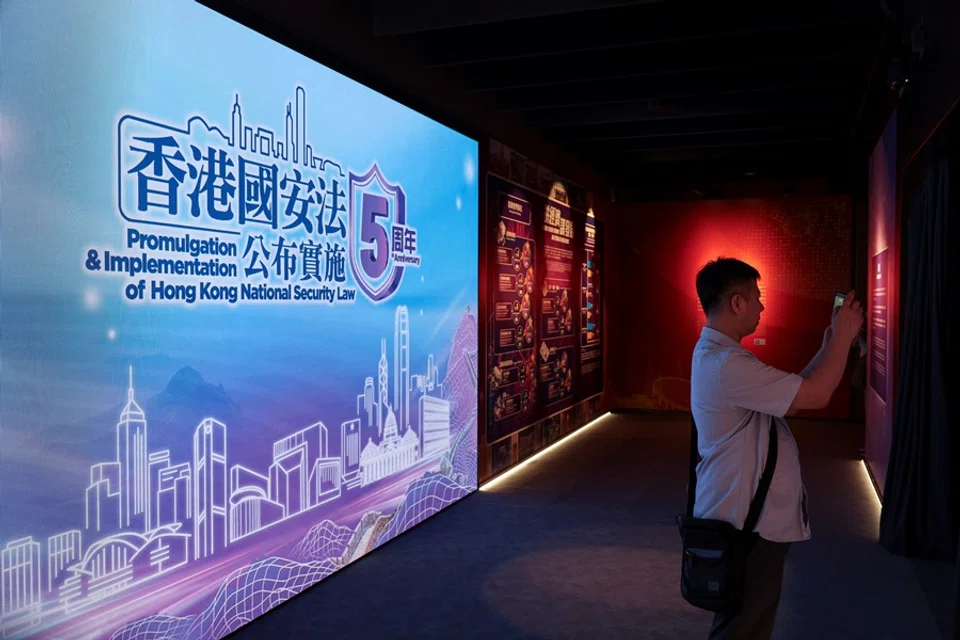

Hong Kong entered a new era following the implementation of the Hong Kong national security law five years ago. The anti-establishment and anti-mainland sentiments that surged during the 2019 anti-extradition bill movement have gradually subsided, and the unrest that once swept through the streets has died down, giving way to a profound reshaping of the city’s political landscape, economic structure, social atmosphere and cultural identity.

Amid this dramatic transformation, Hong Kong residents like Yeung are trying to adapt to the new reality as best as they can, while also striving to preserve the familiar memories of Hong Kong in various ways.

“We also focus more on local businesses, like independent bookshops of this kind, which I frequent. I’m really afraid that things produced in Hong Kong will vanish.” — Wang Yuxuan (pseudonym), a 26-year-old engineer

Wang Yuxuan (pseudonym), a 26-year-old engineer, is also an advocate for Hong Kong culture. On a Saturday night in late May, he attended a book club at independent bookshop Have A Nice Stay, and discussed Hong Kong youths’ mental health and social media habits.

He told Lianhe Zaobao, “What youths care about now are the topics that can still be discussed in society. We also focus more on local businesses, like independent bookshops of this kind, which I frequent. I’m really afraid that things produced in Hong Kong will vanish.”

Wang found a sense of belonging in a space like Have A Nice Stay. Located in the bustling Mong Kok district, this bookshop was founded by several former journalists in 2022, selling books that explore local issues, such as Hong Kong Historical Shops (《香港老铺录》), Hong Kong Department Store (《香港百货》) and Decoding Romantic Transport Enthusiasm (《浪漫交通迷解码》).

Mandy, a 29-year-old staff at the bookshop, told Lianhe Zaobao that the bookshop prioritises books related to the media, as well as Hong Kong’s society, culture and history. “In today’s society, many things lack a visible public platform, but there are still many people and groups from various fields making an effort,” she noted.

Speaking out amid a new normal

Mandy is also a journalist for the bookshop’s online magazine Subtext (《留白》), which focuses on topics related to Hong Kong society, people’s livelihoods, arts and culture. Recently, Mandy has been paying attention to the plight of the deaf community in Hong Kong.

In terms of its editorial policy, Subtext admits on its website that for certain topics, it can only “flash a wry smile and let it go”. However, it also states: “None of us want to see a situation where, when discussing today’s Hong Kong, all that’s left is a ‘brand new Hong Kong’ (美丽新香港). This is too unfair and apathetic for locals who are still fighting with all their might. All of us believe that there are still many things that can be done.”

... current students are primarily concerned with whether Hong Kong is losing its unique urban characteristics. — Associate Professor Rose Lüqiu, Department of Journalism, Hong Kong Baptist University

Amid the new normal of a persistently sensitive political environment and tightening space for expression, Subtext, along with many Hong Kongers who still care about the city, continue to express their concerns in feasible ways.

Rose Lüqiu, an associate professor at Hong Kong Baptist University’s Department of Journalism and a former prominent media figure, observed that current students are primarily concerned with whether Hong Kong is losing its unique urban characteristics.

She said in an interview, “After the [anti-extradition bill] movement and the implementation of the national security law, people’s concern for Hong Kong has shifted towards culture, language and lifestyle. Everyone still loves this city dearly.”

As for the once-intense anti-extradition bill movement, Lüqiu pointed out that students rarely mention it nowadays; on the rare occasion that someone wants to study this topic, she would advise them to choose a different subject.

She explained that many related archives no longer exist, such as the defunct Apple Daily website. “How would one conduct research?” she asked.

The pro-democracy media outlet, once known for its distinct anti-establishment stance, ceased publication in June 2021 after its founder, Jimmy Lai, was accused of violating the Hong Kong national security law and had his assets frozen. Other Hong Kong media outlets that have since ceased publication include Stand News and Citizen News.

Drawing your own red lines

Today, many have drawn their own red lines, unwilling to touch sensitive political topics.

Wang admitted that even when it comes to general social issues, as long as there is a perceived connection to politics, he keeps mum. He even mentioned that he no longer files noise complaints with the authorities to avoid causing trouble.

Others are also wary. An interviewee talked about a group of Hong Kong youths who are focused on women’s rights issues. Out of fear of being reported, they were “cautious to a fault” when planning activities, striving to keep a low profile despite the topic not being particularly sensitive.

Amid a dramatically changing political environment, more Hong Kongers are choosing to withdraw from public participation.

In fact, the Hong Kong national security law targets acts that endanger national security, such as secession, subversion and collusion with foreign forces. The Hong Kong government has also repeatedly emphasised that the law is aimed at a very small minority and does not affect the basic freedoms of the masses. However, critics argue that the law’s broad definitions make it easily applicable in a wide range of situations, leading to a chilling effect.

Amid a dramatically changing political environment, more Hong Kongers are choosing to withdraw from public participation. For example, following the 2021 electoral overhaul in Hong Kong and the implementation of the “patriots governing Hong Kong” principle, voter turnout in the Legislative Council (LegCo) election that year and the 2023 district council elections reached record lows of 30.2% and 27.54% respectively. The turnout among young people was even lower, generally below 10%.

Several interviewed youths described their inability to change the overall situation as “helplessness”, but they also understand that they cannot languish in negative emotions forever.

Mandy adjusted her mindset in this way: “When certain things happen, I would feel really low and angry, which I know is not conducive. What I can do is remember those feelings and, when the opportunity arises, transform them into something meaningful.”

Normalcy after turmoil

The 2019 anti-extradition bill movement has become an indelible scar in the collective memory of Hong Kong. For Hong Kongers who participated, the anger, chaos and despair of that summer may forever seem like only yesterday.

Forty-year-old Chen Jiahui (pseudonym) was one of the protesters who took to the streets. When asked about his deepest impression of the movement, he mentioned three dates without hesitation: 9 June, 12 June and 16 June. When interviewed, Chen said that his demand at the time was for “true democracy”, and that he does not agree with the violent actions of some protesters or the pro-independence stance.

Now, he is indifferent to politics; at one point, he even avoided all Hong Kong news, not even willing to read about car accidents. “I cared so much about this city, but it has left me just as disappointed.” — Chen Jiahui (pseudonym), a protestor who took to the streets in 2019

It has been six years, but Chen still feels heavy-hearted whenever he recalls the scene of streets filled with tear gas. A close friend who protested alongside him was later arrested and imprisoned. Now, he visits his friend once a month in prison, bringing comic books and chatting about everyday life. “I try so hard to maintain the facade of a normal life in front of him, so that he can be relieved and not worry about me.”

Indeed, Chen’s life has returned to a state of normalcy. He is no longer the passionate young man he was six years ago. Now, he is indifferent to politics; at one point, he even avoided all Hong Kong news, not even willing to read about car accidents. “I cared so much about this city, but it has left me just as disappointed.”

Even so, unlike many Hong Kongers who immigrated after the anti-extradition bill protests, he chose to stay. He shared, “I think I still care most about Hong Kong.”

By staying, he learned to separate his political ideals from his personal fate. He lamented, “Maybe that’s the real world in 2025. There’s no need to criticise the government. If I work hard and perform well at my job, I get paid well. I can then just go out and have lots of fun with my friends. Maybe that’s how people should be like nowadays.”

Chen supports the integration and development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area. He believes that Hong Kong has advantages that the mainland lacks — such as a mature financial system — while the mainland supports an environment conducive to innovation, and that the two are complementary.

With the passing of time, many have become like Chen — though they have not completely let go, they learned to make peace with reality in their own ways.

“Those who wanted to leave have already left. Those who remain must think about how to continue living.” — Lüqiu

Hong Kong Baptist University’s Lüqiu sees it this way: “Those who wanted to leave have already left. Those who remain must think about how to continue living. I often tell my friends that if you choose to stay at this time, taking care of yourself and loving yourself is most important. Lead a normal life and build yourself up, be it spiritually or physically.”

She added, “Do a little more to preserve Hong Kong’s characteristics for that bit longer if you are able to. Although it would feel like it cannot be retained, we can at least slow down its erosion.”

The display of a bookstore in Hong Kong’s city centre seems to silently convey this belief. Books placed prominently at the front of shelves explain the necessity of the Hong Kong national security law, while behind them, a row of books on the anti-extradition protests and other social movements quietly marks the tug-of-war between order and resistance, reflecting the city’s vicissitudes.

Five years of tranquility: is Hong Kong still unique?

Since the Hong Kong national security law was implemented in 2020, the streets have returned to tranquility, and the lives of most people have returned to normalcy — yet now and again, there would be murmurs that Hong Kong is gradually losing its uniqueness, or even complaints that it has become “mainland-ised”, no different from mainland Chinese cities.

On the surface, several instances from the past few years have indeed caught one’s attention:

Some Hong Kong officials suggested that Lu Xun’s works “encouraged students to take to the streets”, and demanded his books to be removed from school libraries. Meanwhile, public libraries had removed books by authors from the pro-democracy camp, including academic research and oral histories that might touch on official taboos, and even travelogues and children’s comics that do not violate the national security law.

Towards the end of the Covid-19 pandemic, there was a heated debate in Hong Kong over whether to “coexist with the virus” or follow mainland China’s “zero-Covid” policy. At that point, a pro-establishment lawmaker warned that experts advocating co-existence could be seen as violating the national security law.

The people involved had consistently been engaged in activities violating national security for a long period of time even before 2019, but others, including investors, have not been affected. Hong Kong’s economic development and the daily life of the people were not impacted. — Lau Siu-kai, Former Vice-President, Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies

Shrinking space for public discourse

A Hong Kong media commentator who wished to remain unnamed told Lianhe Zaobao that the space for public discourse in Hong Kong has shrunk. Now, when writing a commentary, “it should not be written in a high-profile manner, and stays away from certain topics” to avoid pressure on the writers and the corresponding media outlet.

However, some observers do not feel that Hong Kong has lost its uniqueness.

Former Singaporean Foreign Minister George Yeo, who lived in Hong Kong for several years, said, “It is obvious that Hong Kong remains different from Chinese cities. It is in Beijing’s interest to maintain this difference beyond 2047 (50 years on from 1997, when Beijing promised that Hong Kong would remain unchanged for 50 years).”

He stated, “Westerners who live in Hong Kong have no doubt that it is not just another Chinese city. Those speaking from afar are making political statements.”

Lau Siu-kai, former vice-president of the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, told Lianhe Zaobao that both the Hong Kong national security law implemented in 2020 and the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance passed in 2024 (commonly known as the legislate Article 23 of the Basic Law) involved very few cases — just a few hundred. The people involved had consistently been engaged in activities violating national security for a long period of time even before 2019, but others, including investors, have not been affected. Hong Kong’s economic development and the daily life of the people were not impacted.

According to the latest official statistics, since the implementation of the Hong Kong national security law, 326 people have been arrested for allegedly violating the law, with 165 convicted.

... the city basically remains open to information from all over the world, and people can choose whatever they want to view online, including information that does not align with the mainstream narrative. This is entirely different from mainland China... — Chan King-cheung, a veteran Hong Kong journalist

“Hong Kong‘s uniqueness within China definitely still exists”, stated veteran Hong Kong journalist Chan King-cheung when interviewed, adding that under “one country, two systems”, Hong Kong allows free movement of people and capital. Hong Kong’s judicial system implements the common law, and the city basically remains open to information from all over the world, and people can choose whatever they want to view online, including information that does not align with the mainstream narrative. This is entirely different from mainland China, and is a crucial distinction with regard to Hong Kong’s status as an international financial and arbitration centre.

Overall, since Hong Kong’s return in 1997, the city has continued chugging along. While it operates under a different system from that in mainland China, the lifestyles of the average person in Hong Kong and those from major mainland cities have gradually converged.

However, one key distinction remains: outside the Beijing-recognised and supported pro-establishment camp, Hong Kong previously had another political force known as the pan-democrats or opposition. This group had significant influence in areas such as ideology, education, culture and media.

For example, the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, made up of teachers from various institutions, with over 90,000 members at its peak. It was at one point the largest single-industry trade union and pro-democracy organisation in Hong Kong. It was also criticised as a “malignant tumour” that contributed to political radicalisation among some Hong Kong students.

Apple Daily, known for its controversial reporting style and content, was seen by its supporters as one of the few or even the only media outlet in Hong Kong not “red-washed”, given its consistent criticism and commentary on Beijing, the Hong Kong government and the pro-establishment camp; but it was also criticised by detractors as an incendiary source of “fake news, toxic news”.

In the earlier years, pan-democratic parties often won 60% of the seats in district elections, leading to the “6:4 golden ratio” theory in Hong Kong elections (where pan-democrats and pro-establishment received a 6:4 vote ratio). Pan-democratic members who were elected would often openly express political dissent, and would employ tactics such as filibustering to delay or obstruct the passing of government bills — and even mobilise large-scale protests or marches. For instance, events like the annual 4 June candlelight vigil in Victoria Park that began in 1990 and the 1 July marches that started in 2003 fell under pan-democratic strongholds.

“Politics has been completely purified — only one-sided voices remain. Anything that diverged from the mainstream political line is now gone.” — Chan

Over 100 pro-democracy and civil groups disbanded

Following the 2019 anti-extradition protests, Hong Kong’s social order plunged into crisis. Beijing responded by implementing the Hong Kong national security law in 2020 to stabilise the situation. In 2021, it further reformed Hong Kong’s electoral system by introducing the Improving Electoral System Ordinance, thereby enforcing the principle of “patriots governing Hong Kong”, and fundamentally reshaping the city’s political landscape.

According to Chan King-cheung, the introduction of the national security law and electoral reforms “basically ended all channels through which the pro-democracy camp could participate in the governance of the special administrative region, including the district councils, LegCo, executive council and all positions within the establishment, as well as many of the previously established gatekeeping mechanisms.”

Online statistics show that since 2020, over 100 pro-democracy media outlets, political parties or civil society organisations in Hong Kong have ceased operations or disbanded due to political pressure, frozen assets, arrest of leaders, or fear of prosecution.

“This has had a huge impact,” Chan said. “Politics has been completely purified — only one-sided voices remain. Anything that diverged from the mainstream political line is now gone.”

... at the very least, the Hong Kong government is more effective now that its LegCo is no longer paralysed. He added that Chief Executive John Lee is doing well on the whole but faces huge challenges. — George Yeo, Former Foreign Minister, Singapore

George Yeo: Hong Kong’s LegCo no longer paralysed

For some observers, recent political changes in Hong Kong are not entirely negative. George Yeo remarked that at the very least, the Hong Kong government is more effective now that its LegCo is no longer paralysed. He added that Chief Executive John Lee is doing well on the whole but faces huge challenges.

Lau Siu-kai said that Hong Kong’s past political environment was very loose and liberal, but at the same time, the city went through a few decades of unrest and political strife. The situation is now different, changing the way many issues are approached.

He said, “The US is now deliberately and comprehensively trying to suppress China’s rise.” According to post-event investigations and court cases, the unrest in Hong Kong over the past decade — especially the 2014 Occupy Central movement and the anti-extradition protests of 2019 and 2020 — have shown signs of Western interference.

Lau said, “Hong Kong has been used as a pawn to subvert China,” which has made safeguarding national security more pressing. He stressed that the implementation of the national security law was imperative, and that under the Basic Law, Hong Kong was always obliged to enact such legislation.

He also pointed out that many pan-democrats were nurtured by the British government during the colonial period, and were expected to play an influential role after the handover, even seeking partial political power. However, they rejected the legitimacy of the current system and sought to overthrow it, refused to accept the Chinese Communist Party or the People’s Republic of China, and some even pushed for Hong Kong independence — positions that make it fundamentally impossible to operate within today’s political structure.

Chan King-cheung also acknowledged that the pan-democrats were “too deeply distrustful of Beijing.” He said that Beijing had attempted to reach some sort of compromise, having extended olive branches on several occasions, but the pan-democrats consistently viewed Beijing’s various democratisation proposals as insincere, believing that they would ultimately withhold real power and deny Hong Kong true democracy.

Chan noted that while the pan-democrats had a popular vote advantage in Hong Kong, Beijing held the legal and constitutional authority. But due to a lack of mutual trust, “the two sides couldn’t come together, so conflict was inevitable, and something big was bound to happen.”

Governance structure reshaped

In the aftermath of the major conflict, it was not just Hong Kong, the pan-democratic camp, and its supporters who paid the price — the balance of power within Hong Kong’s governance structure also shifted.

George Yeo remarked, “China has kept to ‘one country, two systems’, but there is no doubt that Beijing has a guiding hand in Hong Kong especially on political matters.”

A Hong Kong political observer who declined to be named said when interviewed that when Hong Kong was rocked by the turmoil in 2019, Beijing imposed the national security law as a forceful means to restore order. As a result, Hong Kong can no longer make final decisions on many matters — major decisions are now made in Beijing. Due to vague “red lines”, Hong Kong’s decision-makers act with extreme caution, often avoiding certain sensitive issues, which in turn indirectly affects governance.

Although there are no official bans, many people simply choose not to participate for self-preservation. “In this way, Hong Kong’s soft power has been damaged.” — Chan

Chan King-cheung also noted that Hong Kong used to be a very open part of China, capable of accommodating diverse ideas and free expression. In the past, sensitive academic or international exchange activities that could not be held in mainland China were possible in Hong Kong. But now, these have become high-risk activities. Although there are no official bans, many people simply choose not to participate for self-preservation. “In this way, Hong Kong’s soft power has been damaged,” Chan said.

“Not to mention Hong Kong’s exchanges with Taiwan,” he added. “That line has essentially been completely cut off. There used to be back-and-forth — Taiwan’s elections, cross-strait politics — we could talk about all of that.”

Still, Chan believes that Beijing does not want Hong Kong to become just another Chinese city. With the pan-democrats unable to return, the remaining space for civil society is what needs to be watched.

As time passes, he said, “if Beijing hopes for ‘one country, two systems’ to function better, perhaps it could show a bit more tolerance and more inclusiveness, and recognise and protect Hong Kong’s uniqueness.”

------------------------------------------------------

Timeline of key events in Hong Kong

July 2012

The Hong Kong government’s Moral and National Education programme was criticised as a brainwashing exercise, prompting widespread demonstrations.

September-December 2014

The Occupy Central movement broke out, as pro-democracy supporters took over main streets in the city in campaigning for democratic elections, against Beijing’s future decision on the Hong Kong chief executive on 31 August 2017.

8 February 2016

From the first night of the Chinese New Year to the next morning, a case of unlicensed street hawkers in Mong Kok evolved into violent clashes between police and protesters.

June 2019-January 2020

The anti-extradition bill movement swept across Hong Kong, opposing a proposed amendment to the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance that would allow criminal suspects in Hong Kong to be extradited to mainland China. The movement led to widespread unrest, including clashes between police and protesters, arson, and the occupation of the airport and university campuses. Over 10,000 people were arrested during this period.

30 June 2020

The Hong Kong national security law was passed by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and incorporated into the Basic Law. It defined and criminalised acts such as secession, subversion, terrorist activities and collusion with foreign forces.

2021

As Hong Kong’s political space tightened, major pro-democracy civil society groups such as the Civil Human Rights Front, Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, and the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China were dissolved. Pro-democracy media outlets such as Apple Daily ceased operations — its founder, Jimmy Lai, was arrested under the national security law.

31 May 2021

The Improving Electoral System Ordinance came into effect, reforming the Legislative Council and chief executive election systems to fully implement the principle of “patriots governing Hong Kong”.

23 March 2024

The Safeguarding National Security Ordinance — commonly known as Article 23 legislation of the Basic Law — was passed and enacted by the Hong Kong Legislative Council. It criminalised acts such as treason, insurrection and sedition. The Hong Kong government had attempted to enact this in 2003, but the move was shelved after triggering massive protests.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “他们缄默中守护 心中那一角香港”.