Chinese medicine injections face rigorous regulation for the first time

China’s once-booming market for traditional medicine injections is facing tough scrutiny as regulators demand modern proof for age-old remedies.

(By Caixin journalists Cui Xiaotian, Zhou Xinda and Denise Jia)

The deaths first surfaced in a scattering of headlines: a toddler in Heilongjiang, a patient in Anhui, clusters of severe allergic reactions in hospitals across China. Each case shared one unsettling detail — the drug involved was a traditional Chinese medicine injection, a class of products used for decades, trusted by millions and supported by enormous sales.

Despite their common usage, these injections have long operated in a regulatory grey zone, approved under standards so loose that their clinical effectiveness and safety remain largely unverified.

Regardless of the recurring tragedies, this category of medicine has continued to flourish. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) injections — herbal extracts distilled, purified and delivered intravenously like Western drugs — first entered Chinese hospitals in the mid-20th century. Developed initially to make herbal medicines act faster and hit harder, they have grown into a multibillion RMB market.

One senior pharmaceutical executive calls them “a category that looks like everything and nothing at once”.

Born of necessity

The ascent was swift. The first product, a bupleurum (Chai Hu, 柴胡) injection, emerged during the Second World War, when battlefield infections were widespread and resources scarce. By the 1950s, Wuhan Wuyao Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. had brought it into mass production. By the 1990s, with China’s health system still under resourced, dozens of varieties — Xueshuantong, Shenmai, Qingkailing, Yanhuning — filled hospital approved drug lists. “We prescribed them routinely,” recalled one doctor. “You saw patients improve, and there were few other options.”

But the success concealed a deeper structural problem: these injections sit at the intersection of two pharmaceutical systems and fully belong to neither. They are not traditional remedies in the classical sense, nor do they meet the rigorous standards that govern modern chemical drugs. One senior pharmaceutical executive calls them “a category that looks like everything and nothing at once”. Their definitions remain vague; in practice, they are often grouped simply by the “Z” prefix in their approval numbers.

Even so, TCM injections became deeply embedded in China’s medical and financial systems. Roughly half of all TCM injections are covered by national health insurance — 14 of them at the highest, fully reimbursable tier — and ten appear in China’s essential medicines catalogue. Some have even won low price procurement bids, obligating public hospitals to buy and use them in predetermined quantities. In 2024, a national procurement alliance included eight such products in a 30 billion RMB collective tender.

Closing the loophole

At their peak, annual usage exceeded 400 million patient visits, and yearly sales reached into the hundreds of billions of RMB. But scale brought risk. From the early 2000s onward, reports of adverse reactions — including deaths — became impossible to ignore. In 2004, one injection caused 18 cases of acute intravascular hemolysis, the breakdown of red blood cells. In 2006, an allergic reaction to a Houttuynia injection killed more than ten patients. Similar incidents followed, each associated with serious injury or death.

Still, regulatory inertia persisted. Lax approval standards from earlier decades meant that once a product reached the market, it was rarely removed. Safety reviews for TCM injections began in 2009, but effectiveness reviews stalled for years, allowing any products with scant clinical evidence to remain in use. “Globally, there is no precedent for injectable formulations made from natural raw materials with such simple processing,” said Zhou Chaofan, a researcher at the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences and member of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. “Nor for injections whose active ingredient content only needs to exceed 70% of total solids.”

Government responses often came indirectly, via the health insurance and hospital systems rather than drug regulators. Most TCM injections were restricted to secondary hospitals and above. Tertiary hospitals in Beijing and Shanghai quietly stopped stocking them. But in smaller cities — particularly in China’s northeast and west — physicians continued using them heavily, sometimes even for routine respiratory illnesses.

Industry insiders predict that half, or even two thirds, of existing products will disappear.

Now, after more than a decade of debate and delay, reform is finally arriving. In late 2023, China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) formed a 28 member expert group led by academician Zhang Boli, one of the country’s most influential TCM advocates. Two years later, in September and October 2025, the agency released two draft regulations that industry veterans described as the strictest ever written for the category.

For the first time, every TCM injection approved before 2019 must undergo rigorous post market evaluations for both safety and effectiveness. Companies unable to prove that their products meet modern clinical expectations will lose their registrations. Those that remain must conduct new trials and generate complete, auditable data within five years — a process akin to developing a new drug from scratch.

Industry insiders predict that half, or even two thirds, of existing products will disappear.

New era of accountability

For decades, Chinese herbal injections have operated in a regulatory grey zone — medically controversial, financially successful and lightly overseen. Now, two new draft regulations are pushing the sector to an unprecedented reckoning.

The first, released on 19 September, is a joint policy from the NMPA, the National Health Commission and the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine is entitled the Notice on Promoting Post-Market Evaluation of TCM Injections. It requires all manufacturers to reassess the safety and effectiveness of all previously approved products. The policy adopts a three-pronged strategy: encourage voluntary evaluations, mandate reviews for higher-risk products and phase out any that fail modern scientific tests.

The second document, published on 17 October by the NMPA’s Centre for Drug Evaluation, is even more consequential. The Basic Technical Requirements for Post-Market Research and Evaluation of TCM Injections lays out — for the first time — how these evaluations must be conducted. The expectations are rigorous: the entire reassessment process mirrors that of developing a new drug, from lab chemistry and toxicology to randomised controlled trials.

“These guidelines essentially ask companies to repeat the entire development pipeline under modern drug registration standards,” said Qiao Chunsheng, chief executive of Beijing Duheng Zhidao Medical Technology Co. Ltd., a contract research organisation that specialises in TCM products. He said four or five companies with best-selling TCM injections — each generating more than 100 million RMB (US$14.1 million) a year in sales — have already approached him for research partnerships.

A major change is the requirement to justify the need for an injection in the first place. If an effective oral medication already exists, higher-risk injectable versions may no longer be acceptable.

Industry reaction has been swift but wary. Another contract research executive, Chen Jie, deputy head of the TCM division at Beijing Sunshine Hohe Drug Research Co. Ltd., reported similar demand. His inquiries come from companies whose products appear in the national insurance catalogue, often with annual revenue above 50 million RMB. “They have the margins to invest in this,” he said.

There is little room for shortcuts. Companies must begin with comprehensive pharmaceutical research — chemical fingerprinting, identification of active ingredients and stability testing. Only after passing toxicology and pharmacology reviews can they move to the far more expensive clinical phases. In principle, the final stage must be a randomised, controlled, multicentre trial — the gold standard of evidence-based medicine.

“This tells us the regulator sees serious controversy in these products’ clinical rationale,” said Han Sheng, deputy director at Peking University’s International Center for Pharmaceutical Management. “If an injection needs a new randomised controlled trial to justify its existence, it means its real-world clinical rationale is in dispute.”

A major change is the requirement to justify the need for an injection in the first place. If an effective oral medication already exists, higher-risk injectable versions may no longer be acceptable. Many injections used for common ailments such as colds, coughs, or fatigue may be eliminated, while those used for acute cardiovascular events, oncology support or specific pain management — where injections provide clear clinical value — may remain.

Previous efforts to improve safety often relied on retrospective “real-world” data from large hospitals. Many firms collected tens of thousands of cases to support safety claims. This time, such scattered datasets are unlikely to suffice. “A lot of older data is patchy,” Qiao said. “Big hospitals rarely use these products anymore. Smaller ones may lack the quality controls or statistical rigour regulators now expect.”

Analysts estimate that compliance costs will be prohibitive for many manufacturers. A single prospective safety study may require 3,000 patients and cost up to 15 million RMB. A randomised efficacy trial could cost another 25 million RMB. Add pharmaceutical research, regulatory filings and production upgrades, and the total rises to 40 million RMB per product, per indication.

And there is no safety net. Under the new rules, every injection must renew its five-year drug registration. If companies fail to conduct post-market research, the licence will be revoked. If the research is completed but shows the product is ineffective, unsafe or otherwise unsuitable for human use, it will also be pulled from the market.

“This is no longer optional,” said Sunshine Hohe’s Chen. “If you want to stay in this market, you do the work — or you’re out.”

Long road to regulation

China’s effort to reassess the safety and efficacy of TCM injections isn’t new. It is the latest chapter in a long, winding saga — marked by public health scandals, industry reluctance, regulatory delays and a deep mismatch between legacy products and modern pharmaceutical standards.

Between 2006 and 2009, several widely used injections — including Houttuynia, Yinzhihuang, and Shuanghuanglian — were linked to severe adverse events and patient deaths. Emergency suspensions triggered a public outcry and renewed scrutiny of the scientific basis of TCM injections.

“There’s no denying that these products played a role in earlier eras,” said Wang Heng, a veteran industry expert. “But clinical evidence must evolve. What was acceptable 20 years ago may no longer meet today’s standards.”

Many injections entered the market before China’s modern drug review system was established in 2015. Some received approval after minimal clinical testing. “We had a drug with strong immune-modulating effects,” said Wu Heng (not his real name) a former executive at a leading TCM firm. “We kept trying to weaken the protein properties, but it still triggered immune responses. Eventually, we had to abandon it.”

Part of the challenge lies in the inherent complexity of TCM formulations. Many injections contain multiple active compounds with unclear mechanisms.

In 2009, the former drug regulator launched its first safety reassessment campaign for TCM injections, calling for detailed reviews of formulation logic, manufacturing quality and clinical use. A year later, technical guidance was issued, and several products — including Houttuynia and Yujin injections — were placed on a priority list. Companies were asked to submit supplemental nonclinical and clinical data. But the effort soon stalled.

Momentum returned only in 2017, when regulators revived the initiative as part of broader drug approval reforms. A State Council opinion required reassessment of all existing injections within five to ten years. Despite the ambition, progress remained limited.

Part of the challenge lies in the inherent complexity of TCM formulations. Many injections contain multiple active compounds with unclear mechanisms. Unlike chemical drugs, their effects cannot be predicted using standard pharmacological models. Designing clinical trials is difficult — especially when these products do not align neatly with Western diagnostic categories.

“There’s a mismatch in methodology,” said Peking University’s Han. “You can’t test these drugs using purely Western endpoints. Some have delayed onset, some are used in combination with other treatments. Trial design must reflect that reality.”

Even companies willing to comply face major hurdles. Over 130-plus injection products are protected by proprietary patents, and their exact compositions are often not fully disclosed to regulators. Industry insiders estimate that full reassessment could cost 20 million RMB or more per product and take up to five years. “There’s no standard, and no money,” said Wu.

Until now, regulators relied mostly on soft-touch interventions — label updates, insurance exclusions, hospital use restrictions — to limit overuse. A handful of firms conducted observational studies or Phase IV trials, but comprehensive reassessment has remained out of reach.

Cracks in the billion-RMB club

For three decades, China’s TCM injection market experienced unchecked growth — fuelled by low production costs, easy hospital access and consistently high margins.

According to a senior pharmaceutical executive, injections have remained solidly profitable even after years of price cuts. Wu, who worked at a century-old TCM company, said early marketing tactics revolved around pairing injections with intravenous infusions, offering rebates that once exceeded 70%. High margins and easy access made injections far more attractive than oral TCM products. Nearly 80% of prescriptions, he noted, were written by Western-medicine doctors rather than TCM specialists.

“The top-selling oral TCMs barely crack 3 billion RMB in annual sales,” Wu said. “But a single injection can hit 4 billion RMB. At one point, there wasn’t a single oral drug among the TCM top ten.”

As regulatory scrutiny tightened and standards rose, the pipeline for new injections slowed. Technical barriers limited generics, increasing market concentration and distorting incentives. “The top-selling oral TCMs barely crack 3 billion RMB in annual sales,” Wu said. “But a single injection can hit 4 billion RMB. At one point, there wasn’t a single oral drug among the TCM top ten.”

Today’s leading injections fall into three categories: cardiovascular and circulatory disorders, respiratory illness and energy-replenishing tonics. Between 2017 and 2023, three blockbuster products surpassed 20 billion RMB in cumulative hospital sales across all channels, according to Pharnex Cloud data: Xueshuantong lyophilised powder (4.68 billion RMB), Xuesaitong lyophilised powder (3.89 billion RMB), and Shenmai injection (2.25 billion RMB). Qingkailing and Shengmai injections also topped 5 billion RMB each.

Major producers — including Guangxi Wuzhou Pharmaceutical (Group) Co. Ltd., Harbin Zhenbao Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. and KPC Pharmaceutical Inc. — each generated over 10 billion RMB in cumulative sales during the same period.

As of 2024, 58 injection products are listed in the National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL).

But national volume-based procurement, now in its third round, has driven down prices. The 2024 batch included Yanhuning, Xiyanping, and Qingkailing injections, with average cuts of 68%. Lower prices may increase due to favourable reimbursement rules, but unit revenues are collapsing.

At the same time, provincial governments are cracking down on “suspiciously overpriced” TCM therapies. Beginning in 2024, several provinces targeted treatments with tenfold cost disparities or daily therapy prices above 100 RMB. Some lists named marquee brands such as Shuanghuanglian and Chaihu injections. Agencies now require daily treatment costs be capped at roughly 5 RMB.

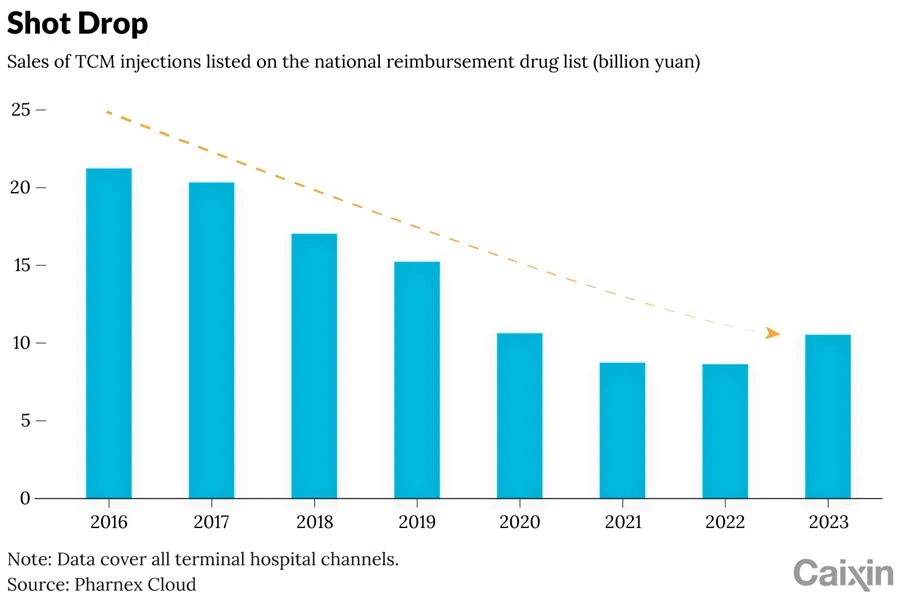

These interventions come as the once-booming injection market undergoes contracts. Hospital sales of NRDL and essential-medicine-listed injections fell from 21.2 billion RMB in 2016 to just 8.6 billion RMB in 2022, their lowest point in years. A modest rebound to 10.5 billion RMB emerged in 2023, driven in part by looser reimbursement policies.

Even flagship products have suffered steep declines. In 2024, TCM injections made up 33.6% of China Shineway Pharmaceutical Group Ltd.’s revenue, yet sales of its core products — Qingkailing and Guanxinning injections — fell 40.8% and 52.7% respectively. Net profit dropped 13.4%.

Kanion Group Co. Ltd., maker of Reduning and Ginkgo injections, reported revenue and net-profit declines of nearly 20%.

Some companies exited entirely: in February 2025, Dali Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., which produces Xingnaojing and Shenmai injections, was delisted after its market cap fell below 500 million RMB. Kunming Longjin Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. warned in April that it too may face delisting, citing shrinking coverage after restrictions on Dengzhanhua injections in lower-tier hospitals.

Reform as industry lifeline

After two decades of delays, the overhaul of TCM injections is poised to reshape the sector’s entire innovation pathway.

The stakes are high. China has 868 active TCM injection approvals across 127 formulas, made by 186 companies, according to Pharnex Cloud data. Industry observers estimate only one-third will survive.

“Only products with annual sales over 100 million RMB are likely to invest in post-market studies,” said Duheng Zhidao’s Qiao, noting many firms are commissioning potential assessments on older formulas. In 2024 alone, 400 drug approvals spanning 48 injection varieties surpassed that threshold, led by products like Xuesaitong, Ciwujia, and Shenmai injections.

Hundreds of smaller products are likely to disappear. One executive told Caixin their company had no plans to pursue reassessment for a TCM injection with annual sales under 1 million RMB. “Its golden age is long over”.

For years, scale — not innovation — dominated competition in the injection market, said Wu. The new evaluation system will force consolidation and impose tighter regulatory scrutiny on everything from sourcing to manufacturing quality.

For patients, the shift represents a long-overdue win. Adverse events — including deaths —have drawn national concern. With unclear mechanisms and inconsistent production practices, small firms using outdated processes pose particular safety risks.

“Roughly a third of TCM injections should be actively promoted for their clinical effectiveness,” said academician Zhang. “But another third lack both efficacy and safety. The rest must catch up through additional research.”

Innovation, however, has lagged for years. In 2015, a sweeping data-verification campaign led to the withdrawal of more than 70% of drug registration applications — many involving TCM — drying up approvals for years.

Regulators have since introduced a three-tier classification system for TCM drugs: innovative medicines, modified formulations and classical compound prescriptions. A 2023 regulation further clarified differentiated evaluation pathways. TCM injections — typically selected through pharmacologic screening rather than traditional theory — must now undergo full clinical trials.

Whether this framework applies directly to the current reassessment remains unclear. “It may serve as a supplementary reference rather than a decisive method,” said industry expert Wang. “TCM has its own logic, but it must also meet scientific rigour.”

Without clinical guideline inclusion and data-backed validation, TCM injections are losing credibility and market share. Generating real-world evidence is the only way forward.

High-level policy backing has continued to strengthen. From the 14th Five-Year TCM plan (2022) to the 2025 “Document No.11” on quality upgrades, Beijing is pushing for innovation while weeding out subpar products.

Still, many consider injections the industry’s most vulnerable flank. “It’s a collective effort,” one executive said. “If any link fails — manufacturer, regulator, or doctor — the whole ecosystem is compromised.”

For that reason, the new evaluation is widely viewed not just as a regulatory squeeze but as a lifeline. “This isn’t a crackdown,” said Peking University’s Han. “It’s a chance for survival.”

Without clinical guideline inclusion and data-backed validation, TCM injections are losing credibility and market share. Generating real-world evidence is the only way forward.

Huang Luqi, vice head of the National Administration of TCM, acknowledged in a media interview that many injections lack international-grade evidence. “Evidence-based evaluation is no longer optional — it’s the future,” he said.

Industry expert Wang agreed, calling the reform a pivot from experience-based to evidence-based medicine. Yet he also warned: “This can’t be another policy that sits on a website. It has to be implemented from top to bottom — by regulators, pharma firms and clinicians alike.”

Transparency will be essential. Wang called for third-party academic reviews of the hundreds of TCM injections still in circulation — identifying what works, what doesn’t and what may be harmful.

“Right now, we lack access to companies’ raw clinical data,” he said. Without funding or mandates, research teams can’t help. But breaking these barriers is crucial — it’s the only way to build real, unbiased science.”

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Cover Story: Chinese Medicine Injections Face Rigorous Regulation for the First Time”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)