Hong Kong fire aftermath: Strong community spirit, shared pain

The tragic fire at Wang Fuk Court has highlighted the Hong Kong spirit of community, with touching scenes of animal rescue. However, the disaster has also stirred the deep-seated pain lying beneath Hong Kong’s collective psyche. Lianhe Zaobao associate editor Han Yong Hong shares her reflections.

The number of fatalities from fire at Wang Fuk Court in Tai Po, Hong Kong, has reached 159. Although the five-alarm fire in the high-rise building has been extinguished, the resulting trauma and loss, including the grief of the bereaved families and the overnight destruction of homes and property for over 4,000 residents — along with its political impact — cannot be resolved in the short run. One cannot help but feel a deep sense of sympathy for Hong Kong.

... although Hong Kong is a highly commercialised society, its people do not shy away from social welfare and justice issues, proving that this is not a place where “human relationships are as thin as paper”.

Rescuing people and pets

According to information from the Hong Kong government and media, a relief fund set up by the government for disaster victims has received donations amounting to HK$2.5 billion (approximately US$321 million). Many celebrities have also postponed or scaled down their scheduled performances.

Hours after the fire broke out, young Hong Kong residents quickly set up an online “safe and sound” check-in system, working together to verify information, spontaneously creating an information network for the community. All of this once more demonstrates that although Hong Kong is a highly commercialised society, its people do not shy away from social welfare and justice issues, proving that this is not a place where “human relationships are as thin as paper”.

The rescue of small animals is most reflective of the warmth of Hong Kongers. Collating data from various volunteer groups, The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Hong Kong announced that as of 3 December, 80 cats, 11 dogs, 8 birds, 87 fish, 3 reptiles, 21 rodents (such as hamsters and squirrels), 17 snakes, 62 tortoises, 1 hedgehog and 1 pet crab were rescued from Wang Fuk Court. Unfortunately, 70 small animals perished with 173 still unaccounted for.

The level of meticulous care shown by rescuers towards these small lives is astonishing. According to reports, rescued pet fish received oxygen, firefighters performed CPR on two kittens, a 15-year-old poodle was safely rescued by a firefighter, and another managed to save nine cats and a dog. It was said that a pet owner who was not at home during the fire was concerned about his pets inside. The next day, when he saw via his home’s closed-circuit surveillance cameras that firefighters had broken in, he used the intercom function to guide them to various corners of the house to find and rescue all his nine cats and one dog.

The empathy shown towards small lives and their owners reflects the unique tenderness of Hong Kong society, its respect for vulnerable lives, and an egalitarian attitude towards all life.

Besides firefighters, more than a dozen volunteers from several animal welfare organisations entered the disaster area with rescue tools to save pets.

Possibility of veering towards extremes

These events have sparked debate on social media in both Hong Kong and mainland China over the past few days. Critics argued that this is a waste of public resources, while supporters believed that firefighters can be trusted to allocate resources appropriately and would not prioritise rescuing pets over humans. Most Hong Kong residents highly praised the firefighters for not giving up on any life, acknowledging that pets are also considered family members to the victims.

... in a Hong Kong that lived through the “black-clad” turmoil of the anti-extradition protests five years ago, this very capacity for powerful civic mobilisation — and the mindset that comes with it — all too easily prompts suspicion and can indeed veer towards extremes.

The empathy shown towards small lives and their owners reflects the unique tenderness of Hong Kong society, its respect for vulnerable lives, and an egalitarian attitude towards all life. By placing the rights of all living creatures in high regard, civil society can react promptly, organise and mobilise quickly, and take concrete action to uphold the justice and righteousness they believe in. This is the Hong Kong spirit illuminated by the fire at Wang Fuk Court.

However, in a Hong Kong that lived through the “black-clad” turmoil of the anti-extradition protests five years ago, this very capacity for powerful civic mobilisation — and the mindset that comes with it — all too easily prompts suspicion and can indeed veer towards extremes.

Thus, the city’s united, disaster-relief spirit began to shift after only a few days. Over the past weekend, several Hong Kongers were arrested for launching petitions calling for accountability from the government or for allegedly “inciting hatred against the government”. Those detained included a former district councillor, a 24-year-old university student, and a female volunteer. Reports also said that a press conference planned by lawyers, social workers and policy experts was cancelled after the organisers were summoned by the police.

On 3 December, the Hong Kong government issued a strongly worded press release accusing “foreign forces, including anti-China media organisations, and anti-China and destabilising forces” of disseminating fake news and even distributing seditious pamphlets “intended to maliciously smear the rescue work, instigate social division and conflict to undermine the society’s unity in taking forward the support and relief work”.

The statement warned the public not to defy the law, stressing that the Hong Kong government would “exhaust all means to pursue and combat [anti-China and destabilising forces], ensuring that any violation against the law will be pursued regardless of distance through decisive enforcement actions” against all malicious smears or acts inciting hatred.

The Office for Safeguarding National Security of the Central People’s Government also warned that a small number of external hostile forces are seeking to exploit the tragedy, stirring up trouble and creating chaos in Hong Kong.

Stirring up deep-seated pain in collective psyche

In the face of a fire that could have been avoided, Hong Kongers have grief and anger to vent. People feel the need to pressure the government to get to the truth, yet the authorities cannot afford even the slightest lapse, because disaster relief provides a legitimate reason for crowds to gather, and public sentiment is easily stirred.

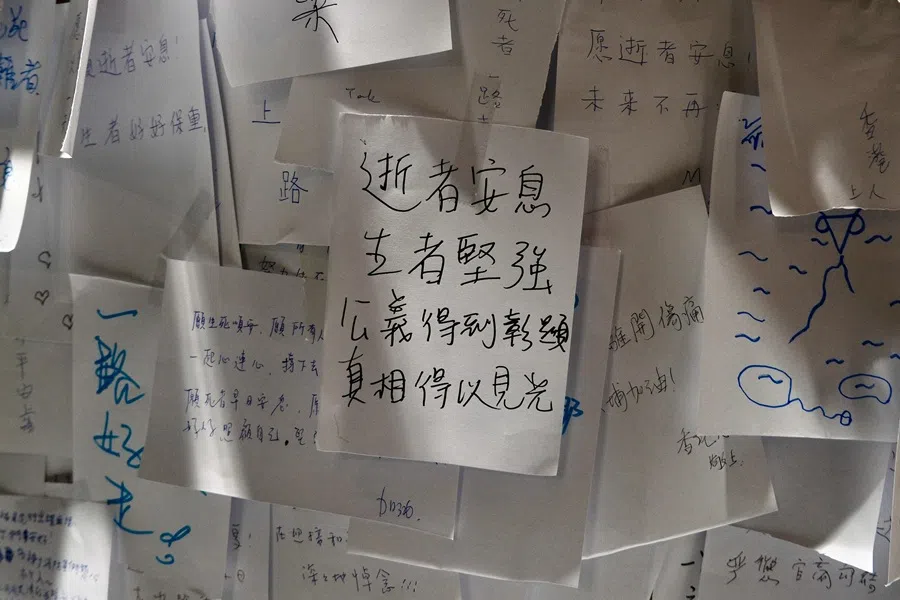

According to a report in The New York Times, the scene around Wang Fuk Court bore echoes of past protests: spontaneously organised volunteers distributing supplies; mourners dressed in black; and public areas plastered with sticky notes expressing sorrow and words of encouragement.

The aforementioned university student who was arrested framed their discontent as “four demands”, all relating to the aftermath of the fire and accountability. The slogans echoed those of the 2019 protests: “Five demands, not one less.”

Hong Kongers’ distrust of the government — including distrust of Beijing — and vice versa, mean that both sides view each other with wariness and suspicion, each believing that a single spark can start a prairie fire.

The Hong Kong government’s way of suppressing public anger has, unsurprisingly, sparked debate and criticism from various quarters. At root, Hong Kongers’ distrust of the government — including distrust of Beijing — and vice versa, mean that both sides view each other with wariness and suspicion, each believing that a single spark can start a prairie fire.

When the public sees administrative failings, they imagine layers of cover-ups or blame it on “mainlandisation”. Meanwhile, the government’s instinct is to “strike down anything that sticks its head up”. Both sides are prone to blow things out of proportion. The fire has once again stirred the deep-seated pain lying beneath Hong Kong’s collective psyche.

Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee has announced the establishment of a judge-led independent committee to investigate the cause of the fire, a move much welcomed by experts. The public needs to know the truth — how exactly the Wang Fuk Court fire started, why the scaffold netting that is supposed to be flame retardant had failed, and whether the responsible departments neglected proper inspections — and they also need to see accountability.

Still, the Hong Kong government has been working hard to manage the situation over the past few days. With so many complex issues to resolve — from the aftermath to questions of accountability — it is worth giving the administration some time.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “宏福苑大火照见香港的爱与痛”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)