From Mao to livestreams: The new face of China’s collective living

Chinese vloggers who have set up communal living arrangements, or “shared homelands”, have been trending online, claiming to offer a new type of home where one eats and lives for free. Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Li Kang finds out if they are sustainable and if there are any strings attached.

“Here, you can eat and live for free, everyone lives and works together. Each of us has a voice and the power to make decisions.”

Speaking to the camera, Wang Yaocheng passionately introduces his “shared homeland” project in Guizhou. In the video, he walks through the mountains, wearing a Zhongshan suit and slinging a military-green canvas bag, prominently emblazoned with the words “Serve the People”.

An alternative way of life

He promises that everything in the shared homeland is free: log cabins, orchards, camping sites, mountain spring water, vegetables and livestock are all shared, allowing people to “truly enjoy a peaceful rural life away from worldly concerns”.

Wang is not the only one with such an idea. In recent months, similar shared homelands have sprung up overnight in places such as Jixi and Wuchang in Heilongjiang, and Baoji and Ankang in Shaanxi. Each vlogger claims to be the “first in the nation” to create a shared homeland.

As for who is the real pioneer, it is quite impossible to verify now. However, whether in the filming techniques or the promotional rhetoric about the concept of “sharing”, there are similarities among them.

The most central and compelling slogan for these shared homelands is still: “A return to the true communal living of the 1960s” — working, producing and then sharing the fruits of labour collectively.

Some bloggers target retirees with slogans such as “health and wellness travel”, while others tug at the heartstrings: “Here, there are no skyscrapers, no bustling traffic — just the rustic charm of rural life and genuine enthusiasm.”

The most central and compelling slogan for these shared homelands is still: “A return to the true communal living of the 1960s” — working, producing and then sharing the fruits of labour collectively.

Vloggers are flocking to the “big communal” concept; is the communal dining (大锅饭) of the planned economy era truly making a comeback?

Older generations of Chinese might be familiar with the collective lifestyle of the late 1950s. The people’s commune movement swept across China in 1958, with private means of production collectivised and commune members eating in public canteens for free; food, accommodation and labour were all collectively arranged. However, the subsequent three years of famine made these public canteens unsustainable, and they eventually faded into history.

Amid China’s economic downturn and the stark wealth gap as well as intense involution, the idea of returning to a collective lifestyle certainly holds some appeal. To an extent, it reflects a yearning by the people to escape the pressures of reality and seek an alternate way of life. After all, in an era where everything revolves around money, there are not many places where you can eat and live for free.

But this begets the question: if everyone is waiting to eat for free, where does the initial funds come from?

Mass following

But this begets the question: if everyone is waiting to eat for free, where does the initial funds come from?

This question circles back to the vloggers who created these shared homelands. According to Wang, he invested all his savings from the past ten years; “I spent millions of RMB just on renovation and setup.” Before returning to his hometown in Guizhou, he ran a jewellery company in Zhejiang.

Fengge (风哥), a blogger from Heilongjiang’s Jixi, said he spent two million RMB (roughly US$280,045) building his shared homeland over time.

Meanwhile, the more forthright Wuchang-based blogger Xiaobei (小北) declared: “I wouldn’t be offering a place to live and eat if I didn’t have some money to spare. But if we’re opening our doors, we shouldn’t worry about how many people come. No one’s going to make me broke just by staying or having a meal here.” As of now, Xiaobei’s Douyin account has amassed over 1.83 million followers.

Assuming funding is not an issue, the next — and more practical — question is: are shared homelands sustainable?

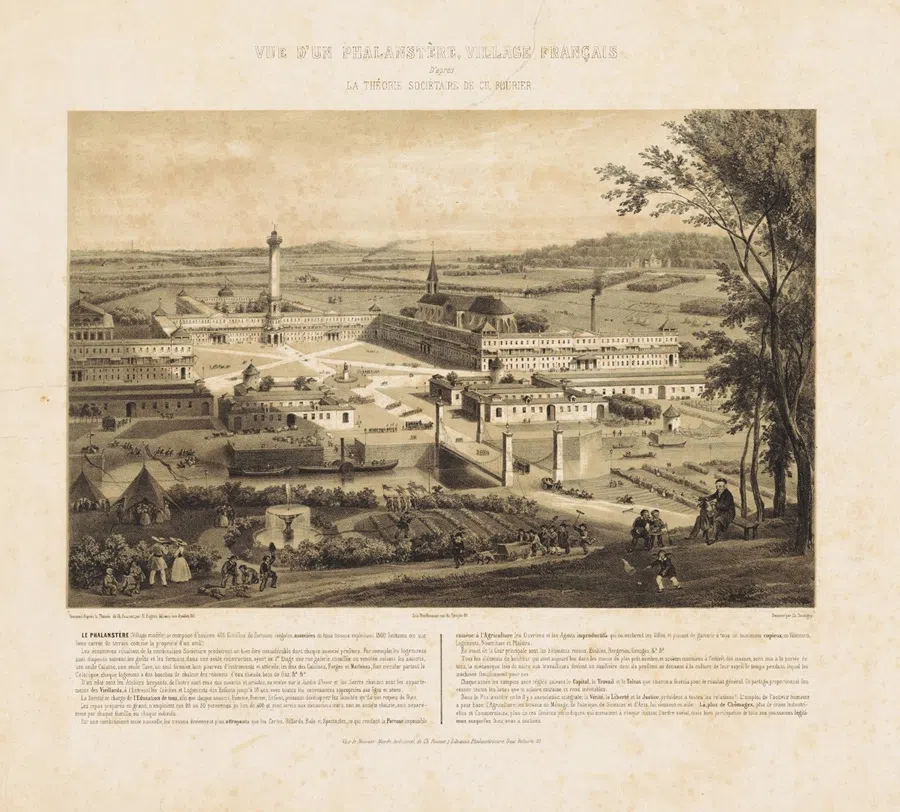

A look through Western history reveals that similar attempts at “shared utopias” have been made — and most ended in failure. For instance, Robert Owen, considered the “father of British Socialism”, founded the New Harmony community, which lasted only two years. Likewise, Charles Fourier’s envisioned utopian community, the Phalanstère, never came to fruition during his lifetime.

China’s shared homeland concept is now facing the test of reality... while it is unclear whether the promised “100 tables for a 1,000-person banquet” was fully realised, the scene showed at least a hundred people in attendance.

China’s shared homeland concept is now facing the test of reality. Fengge’s project, which took five months to build, officially opened on 31 August. From the videos he shared, while it is unclear whether the promised “100 tables for a 1,000-person banquet” was fully realised, the scene showed at least a hundred people in attendance.

By contrast, Wang has not been as fortunate. He claimed that his shared homeland will be completely demolished. He gave no direct explanation as to why, only saying, “I just can’t understand — why would such a good project like a shared homeland face so much obstruction from so many sides?” That video has since been deleted.

In an undeleted video, Wang claimed his rural development project was maliciously misrepresented by “ill-intentioned individuals”. He stated they linked it to negative historical events to smear his efforts.

Truly free?

Meanwhile, Fengge steered clear of historical references, focusing instead on the present by diving into livestreaming. At the “1,000-person banquet” on 31 August, he took to the camera himself, using the feasting crowd as a lively backdrop to promote and sell local agricultural products from his hometown via livestream.

Scroll back a few videos, and you would see Fengge loudly proclaiming to the camera: “Money here is just waste paper — it has no value whatsoever. Because this is a shared homeland, and it has nothing to do with business.”

While the “free” offering is meant for those on the ground in the shared homeland, it is the online viewers of his videos and livestreams who are footing the bill.

While the “free” offering is meant for those on the ground in the shared homeland, it is the online viewers of his videos and livestreams who are footing the bill. This makes sense, as enjoying free food and accommodation while helping generate buzz and becoming part of the backdrop is, in itself, a form of contribution.

I contacted Fengge, extending an interview request and expressing my interest in experiencing his shared homeland. His reply was short: “You have to follow and support me if you want to take part.”

He indeed did not mention any fees, but I noticed that Fengge’s profile photo features the Mao Zedong statue at Orange Isle in Changsha — seemingly a subtle nod to the communal values and revolutionary spirit associated with Mao.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “中国农村“共享家园”重回1950年代?”.