Shedding the passive image: Ethnic Chinese need to step up in US society

Asians are generally known to be humble, tend to keep a low profile, and not strive for leadership positions. However, US academic Wu Guo argues that perhaps it is time for ethnic Chinese to take a leaf from white Americans' book and learn to be confident enough to step up.

As second-generation Chinese immigrants enter the workforce in Europe and the US, there is a growing realisation that outstanding academic achievements and degrees from prestigious schools cannot guarantee sufficient growth opportunities for them in society.

An Asian with a doctorate may never be seen as "management material" in the workplace, while young Asians often become "nameless and faceless" - a characterless and featureless group blurred as one.

Questioned traditional cultural behaviours

In an article published in the US in 2011, an ethnic Chinese author used data from a study to remind readers of this issue. He wrote, "Asian Americans represent roughly 5% of the population but only 0.3% of corporate officers, less than 1% of corporate board members, and around 2% of college presidents."

McKinsey's Women in the Workplace study surveyed more than 400 large organisations across the US in 2021 and found that Asian Americans account for 9% of senior vice-presidents but just 5% of promotions from senior vice-president to the C-suite. Asian American women make up less than 1% of these promotions.

Of course, these statistics and the underlying issues it entails are not new, and there has been ongoing reflection and controversy surrounding this problem. However, I believe it highlights two significant issues.

Over time, children come to see obedience and compliance as the norm, rather than being questioning, insubordinate or innovative.

First, ethnic Chinese families often discourage their children from speaking up and expressing their views. This might be a common problem in ethnic Chinese and East Asian family education, whereby the children's opinions are brushed off or belittled, and they are expected to unquestioningly accept and obey the opinions and arrangements imposed on them by their parents. Parents rarely reflect on the limits of their own knowledge and perspectives, or engage in dialogue with their children as equals.

Over time, children come to see obedience and compliance as the norm, rather than being questioning, insubordinate or innovative. They lack the big picture and gradually become one-track technical talents.

To change the situation, ethnic Chinese parents must forgo such unquestioned "traditional" cultural behaviours, encourage independent thinking, promote some scepticism of authority, develop communication and persuasion as necessary skills, and foster communication and dialogue with their children while listening to their opinions.

'White people do important work'

The second issue, which has seemingly received little attention, pertains to how white Americans establish their identity through self-determination. The second-generation ethnic Chinese interviewed in the 2011 article astutely observed, "White people have this instinct that is really important: to give off the impression that they're only going to do the really important work... It's a kind of arrogance that Asians are trained not to have."

I am well aware that white Americans excel at controlling and monopolising "the really important work", putting themselves in positions of absolute dominance from the outset.

I believe that only the second generation who are born and raised in the US and have a deeper understanding of American social culture can recognise this, because first-generation ethnic Chinese immigrants usually view the US's diversity as a blessing that has helped them survive.

The older generation's understanding of American society remains superficial, and they are unaware of how the dominant group cleverly places itself in the most important positions and controls the overall situation, gradually diminishing the ethnic minorities' courage to effect change.

As someone who has long been concerned about the situation of Asians in American society, I am well aware that white Americans excel at controlling and monopolising "the really important work", putting themselves in positions of absolute dominance from the outset.

In everyday business interactions, white Americans often emphasise what they will not do, rather than taking on everything, presenting their refusal as a mark of superiority. During negotiations, they instinctively emphasise their busyness, popularity, and how many people are waiting in line, creating an impression that customers must lower themselves to make a request, rather than appearing eager to attract customers - they are good at playing hard to get.

When white Americans operate non-franchise local food businesses, they often mark up the prices of simple food, such as sandwiches, so that they can make enough in just half a day, and then rest for the other half. This is in stark contrast to Chinese restaurants, where ingredients are complex and dishes require non-stop cooking at the stove all day, yet prices are affordable.

In fact, the owners (often doubling as chefs) of Chinese restaurants near me almost always develop health problems in their prime years and eventually sell their businesses. A local shop owner who unexpectedly closed her store told me that in a WeChat group of Chinese restaurant owners she joined, many people had developed cancer. In her own store, family members suffer from unexpected health issues due to being overworked.

...the British farmers were not - and never saw themselves as - hardworking peasants, but identified as British gentleman farmers...

In addition to my own experiences and observations, academic research also confirms this cultural tradition of white people maintaining psychological and material advantages.

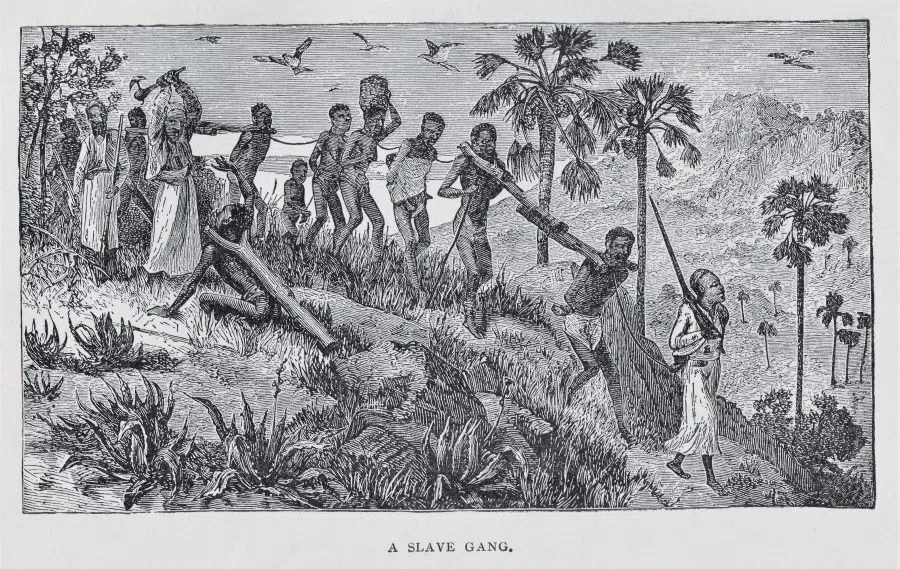

In the anthology The Invention of Tradition edited by British historian Eric Hobsbawm, one writer noted that in late 19th-century Africa, British colonisers immediately strengthened their dominant position by transplanting the gentry and professional class to the new land and inventing traditions. They consolidated their privileged status as inheritors of old European traditions by constructing "new traditions" in the colonies. This cultural status was further bolstered by their military and economic powers.

In all this, the British farmers were not - and never saw themselves as - hardworking peasants, but identified as British gentleman farmers, who profited by controlling the labour of African black people and Afrikaners (South African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers), as well as through their own operations and trade.

Of course, there are complex historical reasons behind the formation of ethnic and racial advantages. However, when combined with the current reflections of Asian Americans on their social status and family education in the US, the examples mentioned above still give some food for thought.

Ethnic Chinese parents should refrain from teaching their children traditional values of being overly humble and keeping a low profile...

Asian-American family education must change

I believe that there are at least two points worth considering. First, Asian-American family education in Western societies must address the chronic problem of advocating obedience instead of effective communication. We have to pay attention to how children express opinions and communicate with parents, and shape the relationship between children and schools.

Furthermore, we have to protect children's rights in school, remind them to be aware of potential unequal treatment or infringements by the school, and encourage them to express their own thoughts to boost their confidence.

Second, as we recognise that the dominant group has strong psychological advantages and self-determination of "who else but me" - the "arrogance" of only doing "the really important work" - ethnic Chinese parents should also have corresponding strategies in educating their children, and at least acknowledge this is a longstanding historical tradition perpetuated by others.

Ethnic Chinese parents should refrain from teaching their children traditional values of being overly humble and keeping a low profile, and instead, gradually shift away from the timid mindset of being "grateful for the diversity" within American society.

Just as ordinary white Americans may project an image of "only doing big things", ethnic Chinese children can also distinguish from an early age "the really important work", and not solely focus on achieving high grades, winning awards and getting into prestigious universities. Instead, they can become individuals who can step up and say, "Let me show you how to do it."

In the American vernacular, the term "leadership" holds positive connotations and is often associated with charisma, management skills, communication abilities, foresight, the ability to create, as well as being able to engage in constructive criticism and improvement of existing systems.

While Asians are often seen as lacking leadership skills, it cannot be denied that some white Americans deliberately maintain a psychological advantage by monopolising the opportunities to demonstrate leadership skills, and subconsciously assign Asians to perpetually serve as robots that are not up for macro-level thinking - this is consistent with the social division of labour implemented by the British colonists in South Africa. If ethnic politics in Western societies mean an endless tussle of interests, rights and self-empowerment, the second-generation ethnic Chinese will certainly benefit from the encouragement to recognise the substance and methods of such politics, and be more aware and actively engage in positive self-determination to gain the advantage.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "别做"没有面孔"的美国亚裔".

Related: Where multiple 'gods' coexist: Countering the racism complex in Western diplomacy | Anti-Asian hate crimes: What makes an American? | Why do Chinese and Indian Americans stay silent during the US anti-racism protests? | Why the Chinese people are invisible in US media | Chinese Americans in the US military: Will their loyalties be questioned in a Taiwan Strait conflict?

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)