Stemming population decline in Chinese first-tier cities

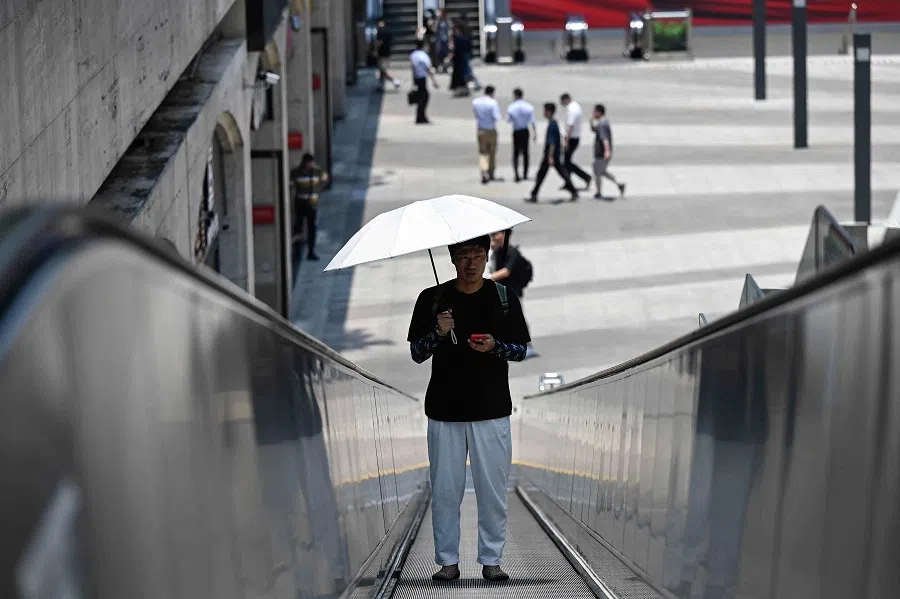

Population figures are going down in China's major cities, not only in Beijing and Shanghai, but also in Shenzhen and Guangzhou. This trend is not only due to higher costs of living, but deeper concerns that prevent economies from finding a certain equilibrium after headwinds. Economist Li Jingkui explains.

According to Guangzhou's 2022 statistics report released on 12 May, the city's permanent resident population stood at 18,734,100 at the end of 2022, 76,500 fewer than in 2021.

Data earlier released shows that Shenzhen's permanent resident population stood at 17,661,800 at the end of 2022, 19,800 fewer than a year ago. Shanghai's permanent resident population also decreased by 135,400 in 2022, while Beijing's population dropped by 43,000.

Thus, all four first-tier Chinese cities have recorded population declines.

What do population declines in China's most economically developed and highly mobile first-tier cities show? Does this trend mark a significant turning point?

Actually, Beijing and Shanghai have experienced population declines before. Beijing is the first first-tier city to experience a sustained population decline. Its population has decreased by nearly 120,000 after six consecutive years of population decline since 2017. Shanghai had earlier discussed ways of controlling its population size; other than in 2022, it also experienced temporary population declines in 2015 and 2017.

... this is the first population decline for Shenzhen since the city's founding in 1979, and the phenomenon is also a rare occurrence for Guangzhou.

However, it is disturbing that Shenzhen and Guangzhou have joined the list of first-tier cities experiencing negative population growth. Both cities have seen their permanent resident population grow by millions over the past decade, and are among the two fastest growing cities in China. Furthermore, this is the first population decline for Shenzhen since the city's founding in 1979, and the phenomenon is also a rare occurrence for Guangzhou.

Other factors besides cost of living

Given the above, it would seem that attributing the cause to the high cost of living in big cities would not be a very accurate analysis.

... cost of living, whether high or low, actually reflects population inflow and outflow.

Firstly, a high cost of living is a relative concept. Looking at the high housing prices and levels of consumption in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, someone from a third- or fourth-tier city may feel pressured to make ends meet by the relatively high cost of living. But living costs are only considered "high" or "low" in relation to income - when incomes are higher, people do not necessarily feel squeezed even if living costs are also higher than that of cities with lower incomes.

Secondly, cost of living is also determined by the population to resource ratio. In other words, cost of living increases because too many people are fighting over too little resources - the market reflects the scarcity of various economic resources through price controls. Thus, cost of living, whether high or low, actually reflects population inflow and outflow.

Aside from this, the population size of big cities will not increase indefinitely. As urban population growth brings about a proportionate increase in benefits, a large economic volume often translates to market concentration where economies of agglomeration can be fully exploited to bring about even greater benefits to the city.

... the city's optimal size stabilises at a certain level and the population does not increase or decrease.

However, urban population growth also adds to the cost of running the city. When this cost exceeds the overall benefits brought about by urban population growth, the city naturally stops expanding. Thus, the city's optimal size stabilises at a certain level and the population does not increase or decrease.

Observably, the high cost of living in a big city is not the reason for negative population growth; on the contrary, a high cost of living is the outcome of urban population growth. Once the size of the city stabilises at the optimal level, the cost of living for people in big cities will not rise indefinitely but also stabilise, forming a stable ratio with the income of people living in the big city.

Conversely, a low cost of living in small cities is also the result of income expenditure equilibrium. It is meaningless to talk about the high or low cost of living if it is not considered in relation to the specific city itself.

If a city's ability to create jobs declines, the income that individuals are able to earn from working also drops.

The importance of jobs

Putting aside man-made laws laid down by the government, we can see that urban population size will stabilise at a level commensurate with people's incomes. But where do people's incomes come from? For people moving between cities, their income should mostly come from work.

If a city's ability to create jobs declines, the income that individuals are able to earn from working also drops. Our ancestors from the nomadic period lived by the waters and the fields; in modern society, we live by cities that give us work.

This is exactly like what Tang dynasty poet Gu Kuang told fellow poet Bai Juyi, "Rice from Chang'an is very expensive! It would be difficult to live there." Even so, young and ambitious men like Bai insisted on going to Chang'an for a simple reason: it was the only place where they could become an official and make a name for themselves. Similarly, if modern youths wish to find a promising job, they have to go to the big cities - not only will there be more job opportunities but also higher salaries.

But according to data released by China's National Bureau of Statistics in August 2022, the surveyed jobless rate for those aged 16-24 reached 19.9% last July, with the figure repeatedly hitting new highs over several months. Employment data from the National Bureau of Statistics in May this year showed that 20.4% of youths aged 16 to 24 were unemployed in April, up 0.8 percentage points from March. This means that since last year, the unemployment rate of Chinese youths, one of the main forces of urban employment in the country, has remained high, with one in five young people out of work.

Against this backdrop, given that the cost of living in big cities will not be significantly adjusted in the short term, the added pressure of unemployment means that it is only natural for population figures in first-tier cities to fall. After all, leaving first-tier cities reduces stress.

Critical to spur internal investment and maintain confidence

So then, the next question is: where do jobs come from?

In the era of globalisation, jobs come from two sources: external demand and internal investment.

Generally speaking, in the absence of major natural disasters or economic stimulus, a country's domestic demand hardly changes. External demand, however, is subject to various variables which could reduce the demand for domestic products, in turn reducing labour demand.

Therefore, internal investment becomes even more important. This avenue of investment is dependent on the decision of entrepreneurs.

If appropriate fiscal and monetary policies are rolled out when that happens, economic recovery would be right around the corner.

Labour demand increases when entrepreneurs invest and start businesses in eager anticipation of future gains. If entrepreneurs do not have confidence in the future, they will not build factories or expand the economy. On the contrary, to endure the winter, they may even downsize and withdraw from their planned investment projects. When that happens, the economy enters into depression, leading to unemployment.

On the other hand, in the event of a brief decline in external demand, the outlook and long-term plans of entrepreneurs will not be fundamentally affected - in the words of renowned economist John Maynard Keynes, people's emotional decisions, driven by "animal spirits", can sway the markets.

Driven by "animal spirits", entrepreneurs quickly seek out new economic opportunities before external demand recovers. If appropriate fiscal and monetary policies are rolled out when that happens, economic recovery would be right around the corner.

It only becomes dangerous if the lack of confidence among entrepreneurs becomes the norm.

People who have left first-tier cities will quickly return too. When forecasts improve and incomes increase, population size will grow. There is no need to worry that a city may become too big because it will be regulated by the "invisible hand" and remain at marginal optimality.

It only becomes dangerous if the lack of confidence among entrepreneurs becomes the norm. If that happens, shrinking investments will lead to long-term economic imbalances, hindering resource allocation optimisation. In the end, the economy will stabilise at a low-level equilibrium.

If this happens, first-tier cities will continue to record negative population growth until the economy shrinks and reaches another equilibrium. By then, the massive group of unemployed people will cast a long shadow on that era. I sincerely hope that this will not happen.

This article was first published in Chinese by Caixin Global as "一线城市人口集体负增长,人们为何要走". Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

Related: How Chongqing's GDP surpassed Guangzhou's to become China's fourth largest city | Chinese provinces' battle for talents and workers after Chinese New Year | China's youths are feeling the pressure from low wages | China's youth unemployment situation could be far worse | Population decline could be a good thing for China | China's declining population cannot be easily reversed

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)