This is what Nanyang art looks like

Following up on his article tracing the origins of Nanyang art and its influence in Southeast Asia, Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre CEO Low Sze Wee explains the characteristics of Nanyang art, highlighting the unique integration of Chinese and Western art in their compositions.

(All photos courtesy of National Gallery Singapore unless otherwise stated.)

The term "Nanyang art" has been much discussed by various artists, curators and researchers. Over the years, "Nanyang" has been applied to even include artists of today, who express local themes in their works. In my last article "What is Nanyang Art?", I argued that "Nanyang artists" should refer to a unique generation of artists, born and educated in China, who successfully furthered their pursuit of modern art in 20th century Singapore.

Experiences in China

In the early 20th century, these China-born artists were exposed to the same cultural environment. Many were educated in art schools that taught both Western and Chinese art. This marked a new generation of artists who were, at least, familiar with, if not proficient in, both art traditions. Many young artists then were drawn to Shanghai, not only for its art academies such as the Shanghai Art Academy and Xinhua Art Academy, but also its cosmopolitan outlook and vibrant art scene.

Artists in Shanghai were exposed to a wide array of artworks and ideas from around the world. Art exhibitions often displayed both Chinese ink paintings and Western-style oil paintings. Many new ideas circulated in the art circles in the 1920s and 1930s. For instance, Ni Yide who had studied in Japan in the late 1920s, wrote about Western art and translated Western texts such as Andre Breton's Surrealist Manifesto.

Due to the political and social turmoil in China, some artists sought refuge by leaving for the various Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, usually referred to as "Nanyang" (meaning Southern Ocean) by the Chinese then. Many had assumed that they would stay in Nanyang for only a few years before returning to China.

However, due to various circumstances, some eventually settled in Singapore permanently in the 1940s and 1950s, after bringing their families and then finding employment, primarily as art teachers. They included artists such as Lim Hak Tai (1893-1963), Chen Chong Swee (1910-1985), Liu Kang (1911-2004), Yeh Chi Wei (1913-1981), Chen Wen Hsi (1906-1991) and Cheong Soo Pieng (1917-1983). In British colonial Singapore, many continued to make art in their new-found home.

So, what did the works of these Nanyang artists look like then?

...many Nanyang artists saw no contradiction between Western and Chinese art. In fact, their preference was to integrate both.

Integration of Chinese and Western art

Many of these artists sought to synthesise Western and Chinese art by relating Western art to their understanding of Chinese art. In the xieyi (写意) Chinese ink painting tradition, artists were unconcerned with physical likeness. They were focused on capturing the spirit or essence of the subject, which reflected the artist's temperament and character. Hence, Western modern art with its emphasis on subjectivity rather than representation, was consistent with Chinese xieyi principles.

For instance, Chen Chong Swee held, in "Zhongxihua zatan" (《中西画杂谈》A Discussion of Chinese and Western Paintings, 1948), that Western art, before the rise of Impressionism, was not concerned with lines. Cezanne, Matisse, Van Gogh and Gauguin only started using linework in their paintings when they needed to convey emotional power and energetic rhythm. This was a direct influence of the Chinese.

In addition, he argued that when Gauguin left Paris in search of a simpler lifestyle in Tahiti, he was following in the footsteps of Chinese artists, who often used landscape paintings to express similar desires of leaving behind their worldly concerns. Hence, many Nanyang artists saw no contradiction between Western and Chinese art. In fact, their preference was to integrate both. As no prescribed methods existed, different artists found their own ways of doing so.

Innovations in ink: light, shade and perspective

Traditionally, ink painters do not pay attention to light and shade in their works. In the mid-20th century, some Nanyang artists started to introduce shading and three-dimensional modelling into their paintings. For instance, in See Hiang To (1906-1990)'s portrait of a Malay boy holding a wayang kulit (traditional shadow play) puppet, the boy's head is depicted in a realistic manner, whereas the rest of the body is rendered in a more xieyi (sketchy) manner.

Likewise, while traditional Chinese landscape paintings usually adopt a moving multiple-point perspective, Nanyang artists like Chen Chong Swee occasionally used the single fixed-point perspective, more commonly found in Western art. In Chen's ink paintings of local villages, trees in the foreground are noticeably larger, and thereby obscure the view of features in the distance. There are also suggestions of shadows cast by the foliage on the ground. These traits are not usually seen in conventional landscape paintings.

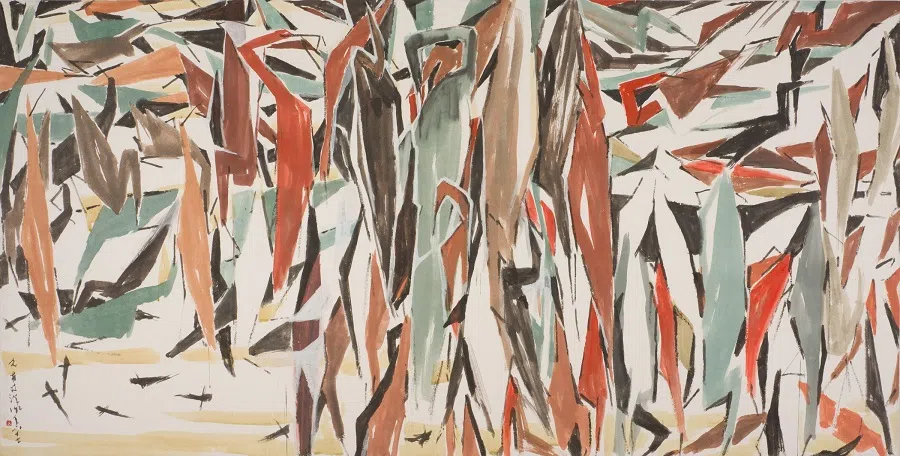

Innovations in ink: modernist styles

Nanyang artists also occasionally incorporated styles drawn from Western modern art movements such as cubism and abstract expressionism into their ink practice. For instance, in some of his semi-abstract landscape paintings, Cheong Soo Pieng used overlapping colour facets, grid-like patterns and amorphous shapes to suggest kelongs - traditional wooden houses built on stilts over the sea - casting reflections on the watery surface. Likewise, Chen Wen Hsi drew inspiration from the fragmented forms of cubism to create interlocking mosaics of coloured planes for his semi-abstract painting of herons.

Innovations in oil: scroll composition

There were similarly innovative approaches in oil paintings. For instance, some artists like Cheong Soo Pieng occasionally used long horizontal or vertical formats for their oil paintings. Such formats are usually associated with Chinese ink scrolls. Local art historian T.K. Sabapathy memorably described this integration as "Scroll Meets Easel".

This may be seen in some of Cheong's works of local village life where the horizontal format lends well to depicting meandering rural scenes. Cheong's predominant use of black linework with thin washes of colour also imbues his oil paintings with the light airy atmosphere associated with Chinese xieyi landscapes.

Yeh Chi Wei also used such horizontal and vertical compositions for many of his works. Such long narrow formats are also found in traditional Indonesian ikat and batik textiles which Yeh was fond of collecting. The colours and motifs in such textiles greatly inspired him.

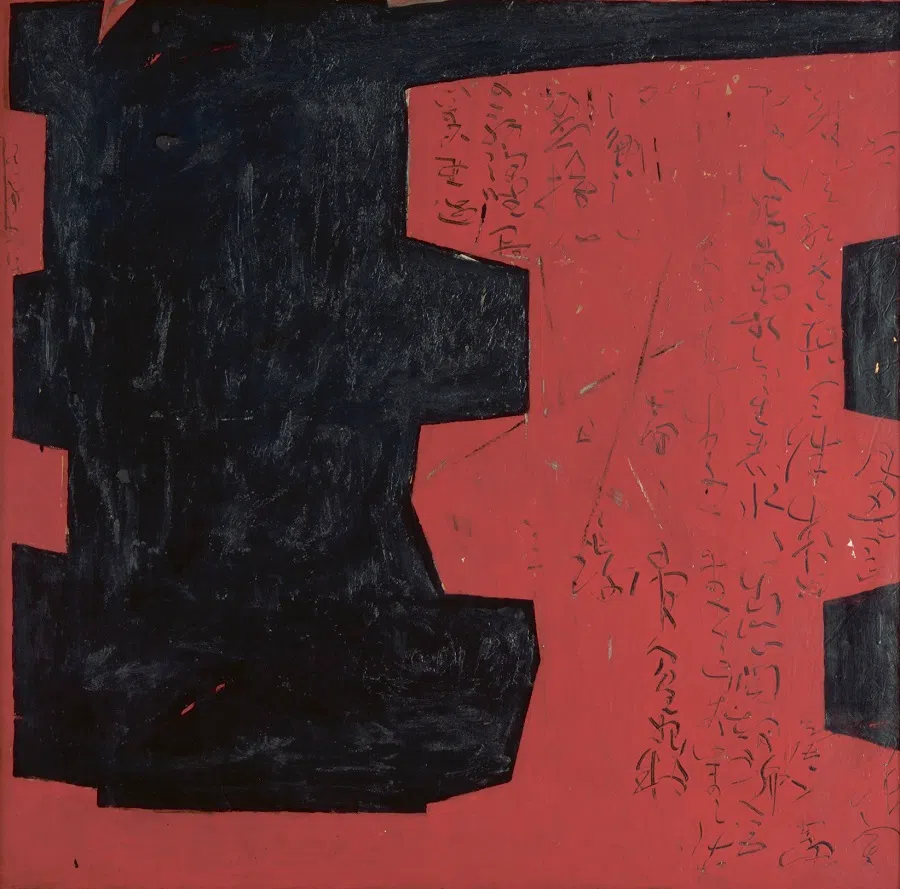

Innovations in oil: Chinese inscriptions

Among the Nanyang artists, Yeh Chi Wei and Chen Wen Hsi also incorporated Chinese writing into their oil paintings. They might have been influenced by the Paris-based artist Zao Wou-ki who had gained international attention in the 1950s for his use of oracle bone script motifs in his oil paintings.

By the 1960s, Chen Wen Hsi started including pictograms and draft script (caoshu 草书), enriching both the content and formal quality in his works. Yeh Chi Wei was fond of using archaic-style inscriptions, usually a mixture of oracle bone (jiaguwen 甲骨文) and seal scripts (zhuanshu 篆书). His paintings had references to traditional woodblock prints, particularly book illustrations, where writing forms part of the overall pictorial composition. In Yeh's works, flat solid colours were used, and an archaic-style inscription was usually rendered in white, akin to the characters found in ink rubbings. Yeh, a proficient calligrapher, was particularly interested in epigraphy and had an extensive collection of such ink rubbings.

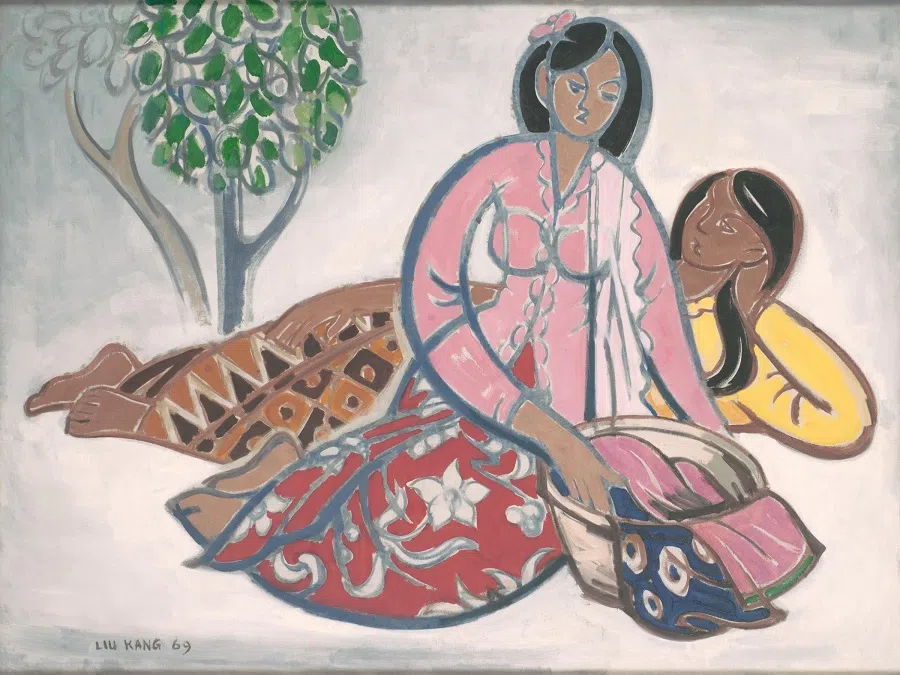

Innovations in oil: linework

Lastly, an emphasis on linework or linearity was also often seen in the oil paintings of some Nanyang artists such as Liu Kang. In his discussion on Matisse, Liu once commented that "[f]rom an Easterner's point of view, what Matisse did was not new because we [Chinese artists] have never stressed chiaroscuro and perspective. We have always counted on lines for depiction and have never been that concerned with realism of the image. We have always aspired to reach that lofty and ancient realm for its purity and elegance."

Upon his return to China in the 1930s from Paris where he had studied art, Liu paid increasing attention to the use of lines in his paintings. As observed by the local art historian Kwok Kian Chow, a gradual thickening of outlines in defining objects and spaces could be discerned in Liu's works, "suggesting an affiliation with the linear brush quality of Chinese ink painting". From Liu's early to late works, there is often evident use of black or dark outlines to accentuate forms and convey a sense of liveliness. This is also apparent in the figurative works of Cheong Soo Pieng, where the willowy forms of local women were captured deftly with smooth flowing lines.

For these younger artists, whilst some emulated the stylistic methods of their teachers, others sought a starkly different path. The latter wanted to use art to effect social change, in particular, the independence of Singapore from the British.

Beginning of a new era

As these Nanyang artists in Singapore matured and found acclaim in the 1950s and 1960s for their formalistic innovations in fusing Chinese and Western art, they were also teaching and mentoring younger artists, most of whom were born in Singapore or had grown up in Singapore after arriving at a young age.

For these younger artists, whilst some emulated the stylistic methods of their teachers, others sought a starkly different path. The latter wanted to use art to effect social change, in particular, the independence of Singapore from the British. Hence, they preferred to create realistic works showing the plight of the poor and working classes, and the injustices of colonialism.

For these artists, their heroes were not 20th century modern art icons like Picasso and Matisse but 19th century Russian realist artists such as Ilya Repin and Vasily Perov who had rejected the conservative attitudes of academic painting in favour of depicting the actual realities of their country. For instance, artist Han Gaoshan admired the works of Repin (such as Barge Haulers on the Volga) because of "how they portray the pitiful life and spirit of labourers in old Russia in an extremely vivid, concrete and realistic manner" ("Yishu yu shenghuo" (《艺术与生活》Art and Life, 1950)).

These developments paved the way for an increasingly plural and vibrant art scene in the years leading up to Singapore's independence in 1965.

Interestingly, the preferences of these young local artists were also aligned with contemporary developments in the newly-established People's Republic of China where realistic works with strong social content formed the dominant discourse. This was, of course, at odds with the artistic inclinations of the Nanyang artists. For instance, at the Yan'an Conference on Arts and Literature in 1942, Mao Zedong called for art to serve the workers, peasants and soldiers. The objective of the forum was to discuss how art and literature could serve the needs of the Chinese Communist Party.

These developments paved the way for an increasingly plural and vibrant art scene in the years leading up to Singapore's independence in 1965. As local artists adjusted to their new-found national identities, they started to regard themselves more as Singaporean artists, marking a new era in how they and others perceived their art.