A Biden presidency: Revenge of the 'Asia-Pacific' over the 'Indo-Pacific'?

The much-ballyhooed "Indo-Pacific" term has gained much traction in the region in recent years. It is believed that the term helps to expand the regional framework to include India as a major power, and balance against China's growing influence. The new Democratic Party platform, however, pointedly excludes the use of the term, and touts the older "Asia-Pacific" instead. Is this Biden's attempt at getting at Trump?

The term "Indo-Pacific" has increasingly replaced the term "Asia-Pacific" in describing the strategic region that links the US to East Asia and Oceania. This in itself is testament to America's unparalleled narrative power. The Trump administration's embrace of the Indo-Pacific, however, is rooted more in partisanship than grand strategy. What would a possible change of administration mean for the much-touted Indo-Pacific concept?

Before the Trump administration adopted the Indo-Pacific regional nomenclature, the Indo-Pacific had only a few, hardy proponents. In the 2013 Defence White Paper, Canberra made the switch from "Asia-Pacific" to "Indo-Pacific" and has been the most vocal advocate for it since. That same year, Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa proposed "an Indo-Pacific wide treaty of friendship and cooperation... not unlike the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia."

Yet, Natalegawa's idea gained little support within ASEAN or more broadly, despite Indonesia being the strongest power in Southeast Asia. Australia's replacement of the "Asia-Pacific" with "Indo-Pacific" appeared more an Oceanic aberration than prophetic. Japan's adoption of the Indo-Pacific framing during the second prime ministership of Shinzo Abe did boost the Indo-Pacific side of the contest over regional nomenclature, but this was not enough to persuade other states to jump on board. Given the woeful state of recent Japan-Korea relations, Abe's adoption of the Indo-Pacific certainly did not help Korean proponents of the concept.

As with Australia and Japan, the Trump administration switched to the Indo-Pacific to provide a framework to expand the regional framework to include India as a recognised major power.

Things changed when the Trump administration, in preparation for the president's first APEC and only ASEAN summit experiences, embraced the Indo-Pacific in late 2017. As with Australia and Japan, the Trump administration switched to the Indo-Pacific to provide a framework to expand the regional framework to include India as a recognised major power. Secretary of State Tillerson's 18 October 2017 speech titled "Defining our Relationship with India for the Next Century" marked this shift in regional nomenclature. As with Australia and Japan, this switch also was about broadening the regional vision and the states it encompasses to better balance against China's growing influence and potential for East Asian hegemony.

Due to the Trump administration's Indo-Pacific switch, Southeast Asian strategic commentary added it to the long list of things that threaten ASEAN centrality (what does not?). China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi derided the switch as "an attention grabbing idea" that "will dissipate like ocean foam".

The Indo-Pacific is very noticeable by its total absence from documents that was approved by the Democratic National Convention on 18 August 2020 ...

China's dissing of the Indo-Pacific concept has done little to douse enthusiasm for it. Instead, a growing number of countries and institutions are making the Indo-Pacific switch. In 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron made the switch;and, in 2019, the French defence ministry released an Indo-Pacific strategy. In June 2019, an Indonesia-led effort saw ASEAN releasing its first ever outlook document, the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. Recently Berlin released a comprehensive set of "policy guidelines for the Indo-Pacific". When visiting Australia in February this year, UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab noted that his government has taken an "Indo-Pacific tilt". And the Trudeau government in Canada is expected to release its own Indo-Pacific strategy soon.

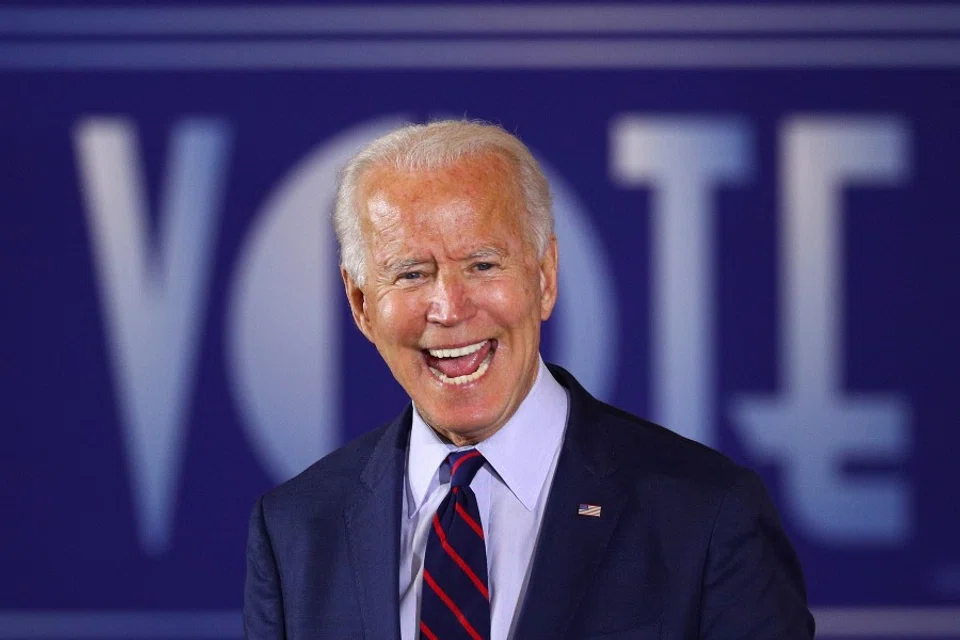

Ironically, it might well be the Americans - albeit of the Democratic variety - who might be doing the dousing. The Indo-Pacific is very noticeable by its total absence from documents that was approved by the Democratic National Convention on 18 August 2020 well after Joe Biden had become the party's presumptive presidential candidate. Buried in pages 87-89 of the recently-released 2020 Democratic Party Platform, the document dealt at length with Washington's approach to the Asia-Pacific, the need for the US to work with its allies and partners and the need to deter Chinese aggression. But the ostensible omission was the "Indo-Pacific" term. The brief sub-section in the last part of the 91-page document that deals with foreign and security policy is titled "Asia-Pacific" and makes the historically questionable assertion that India is an "Asia-Pacific" power. If the omission of the "Indo-Pacific" term is not an oversight and actually one of the many parts of the platform that will see the policy light of day, it may actually help dissipate the Indo-Pacific's frothing foam.

Joe Biden's Foreign Affairs article in the March/April 2020 issue sets out his approach to US foreign and security policy but provides no guidance. It makes no references to the Indo-Pacific or Asia-Pacific. Biden has used the term "Indo-Pacific" before, as noted by the not-disinterested Indian media. Still, the absence of the "Indo-Pacific" from the 91-page document is intriguing, to say the least.

If Biden wins the presidential election next month, his administration may want to retain this part of the party platform. The Trump administration made the switch to the Indo-Pacific as part of its outright rejection of the Obama administration's foreign and security policy that Biden helped realise. Biden, during the heated election campaign, likewise has rejected the Trump administration's foreign and security policy. He promises to restore America's global leadership and return to many of the country's pre-Trump foreign and security policy traditions.

The US, under the Trump administration, popularised the shift from the Asia-Pacific to the Indo-Pacific globally. Might a Biden administration seek to trump Trump, and revive the fortunes of the Asia-Pacific?

This article was first published as ISEAS Commentary 2020/153 "Revenge of the Asia-Pacific?" by Malcolm Cook.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)