[Big read] Guqin doctorate holder holds firm to qin principles

Dr Kee Chee Koon is the first Singaporean to earn a doctorate in qin studies in China. He also has plenty of thoughts to offer on the way of the qin. Lianhe Zaobao journalist Zhang Heyang speaks to the guqin master.

It is not the height of the mountain that dictates its repute; a mountain becomes well known if a deity resides within. Who would have thought that in a typical HDB flat in Singapore lies a collection of Chinese guqin (古琴) dating from the Republic of China era to the Northern Song dynasty? The collector, Dr Kee Chee Koon, a Singaporean born and bred, is the first performer and academic to obtain a doctorate in qin studies under the modern music academy system. From 23 May onwards, 20 guqins including those from Kee’s private collection are on display at the Asian Civilisations Museum.

In the minds of the ancient Chinese literati, qin ranked foremost among the “four arts” of qin, chess, calligraphy and painting (琴棋书画). Its origins are lost to time, but by at least the Spring and Autumn period, the qin had become an important part of aristocratic culture; it is said that Confucius, during his travels across the various states, once went without food for seven days but still insisted on practicing the qin daily. In the Chinese-speaking world, “qin” applies to various musical instruments, such as the piano (钢琴, gangqin), violin (小提琴, xiaotiqin), yangqin (杨琴) and huqin (胡琴), but the character “qin” on its own refers only to the guqin, showing its central position in Chinese culture.

Kee first listened to the guqin in secondary school, when he randomly bought a cassette tape of ancient Chinese tunes: “There were titles like ‘Flowing Water’ and ‘Drunken Fervour’. At the time, I knew nothing. I just felt it sounded odd and very different from the Chinese orchestral music I usually learned, even a little bit creepy, but I couldn’t help but keep listening to it. Looking back, I was surprised by something new due to my own lack of aesthetic sense and knowledge.”

In 1990, Kee became one of the first batch of Singaporean students to study music overseas at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music in China. Initially enrolled in the guzheng programme, he first saw a guqin in person when he checked into his dormitory. “I saw a French girl walk past me, dressed in white with flowing black hair, carrying a black Fuxi-style guqin, like she had stepped out of an ink painting. At the time, I thought that was so elegant, unlike us with the guzheng, having to carry a clumsy stand.” Kee then applied to take up guqin as an elective, and after more than a year of study, officially enrolled into the guqin programme.

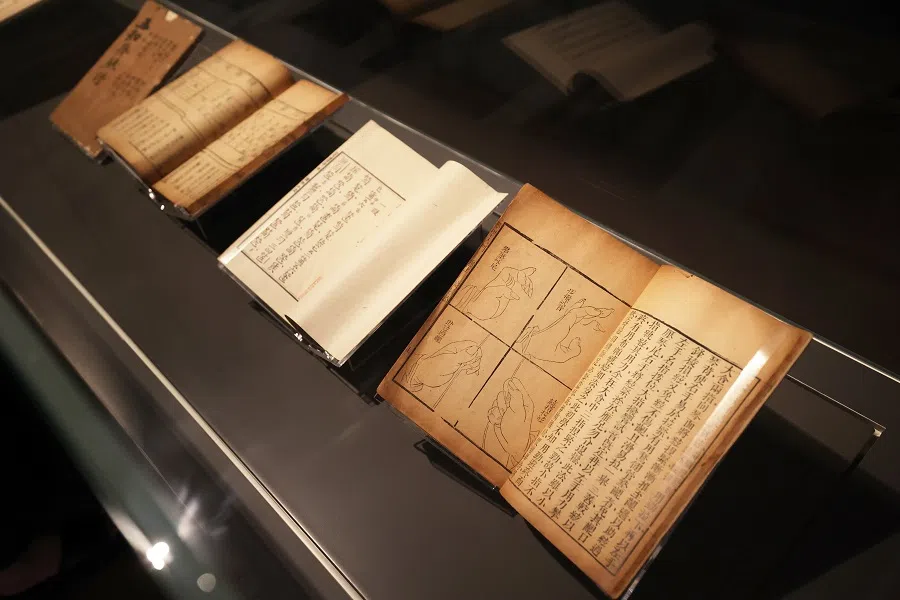

After 12 years, Kee completed transcribing the Yushan School’s Handbook from the Great Restoration Pavilion in 2018, and published the Interpretation of Handbook from the Great Restoration Pavilion.

Transcribing ancient scores

After graduating in 1995, Kee returned to Singapore, performing, teaching and giving cultural talks. In 2006, he went to the China Conservatory of Music in Beijing for further studies under the tutelage of Yushan School guqin artist Wu Wenguang, obtaining a master’s degree and a doctorate, with his research focus on the Yushan School’s ancient scores. After 12 years, Kee completed transcribing the Yushan School’s Handbook from the Great Restoration Pavilion in 2018, and published the Interpretation of Handbook from the Great Restoration Pavilion.

The Handbook from the Great Restoration Pavilion was originally known as the Qingshan Scores (《青山琴谱》), compiled by late Ming dynasty Yushan School guqin artist Xu Shangying (known as Qingshan 青山) and published in 1673, the twelfth year of the reign of Kangxi in the Qing dynasty. It contains 32 qin pieces recorded in jianzi notation (减字谱, shorthand notation), which resembles Chinese characters, but looks like cryptic code. It marks the playing methods and positions for both hands, but omits pitch and rhythm. “Transcribing” requires qin players to keep pondering the aesthetic meaning behind the qin pieces within a specified framework of finger placements, and then objectively interpreting the ancient scores, rendering them into notation that can be played by people today.

“If not for the transcription efforts of masters such as Guan Pinghu, Zhang Ziqian and Wu Jinglue, how would we be able to appreciate pieces like ‘Three Variations on the Plum Blossom’, ‘Flowing Water’ or ‘Guanglin Melody’?” — Dr Kee Chee Koon, a guqin master

Kee pointed out that qin music has a long history in Chinese culture, with historical records of qin pieces by figures such as musician Bo Ya and Zhong Ziqi (said to be either a woodcutter or businessman) of the Spring and Autumn period, to musicians Ruan Ji and Ji Kang of the Three Kingdoms period. However, due to the limitations of ancient notation methods, the oldest qin score collection currently is The Mysterious and Marvellous Tablature (《神奇秘谱》, Shenqi Mipu) compiled by Zhu Quan, a son of Ming dynasty founding emperor Zhu Yuanzhang. Kee commented: “If not for the transcription efforts of masters such as Guan Pinghu, Zhang Ziqian and Wu Jinglue, how would we be able to appreciate pieces like ‘Three Variations on the Plum Blossom’, ‘Flowing Water’ or ‘Guanglin Melody’?”

Such painstaking work is like a pilgrimage against the times. In 2003, the guqin was added to the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and in 2008, its impressive showcasing at the Beijing Olympics opening ceremony sparked a guqin craze in China. As the first guqin PhD holder in China, Kee could have capitalised on that title for fame and fortune, but chose to transcribe in seclusion.

... qin artists never imitated them. They preferred to use singular notes and long notes, and use rhythm and phrasing to bring people into an artistic space moving from ‘real to surreal, far to near’. This blank space is the core of guqin aesthetics.” — Kee

Cautious regard for guqin’s popularity

Kee remains sceptical and cautious about the “popularity” of guqin culture. “I often remind myself that periods where qin-related affairs flourish are usually the days where qin principles decline.” He noted that the guqin has gone through highs and lows in Chinese history; during the Cultural Revolution, qin practitioners were persecuted and their instruments destroyed, yet the music and culture was still passed down. Today, the real threat to qin culture comes from the guqin’s very popularity. “You are not suppressing it, but you are changing its essence, so that it is no longer ‘an elegant instrument making music for self-cultivation’, which is an even more thorough form of destruction.”

He pointed out that some “innovations” in fact deviate from the spirit of the guqin, such as incorporating guzheng playing techniques like tremolo fingering and “rocking finger”, which while enriching in form, actually diminishes the original aesthetic of the guqin, characterised by its interplay of intangible and tangible, simplicity and richness.

“Since ancient times, the qin has always been about change and exploration, but true innovation involves trade-offs”. Kee said: “The pipa techniques of the Tang dynasty were already highly sophisticated; descriptions like ‘pearls large and small dropping on a jade platter’ (大珠小珠落玉盘) have been passed down for millennia. Yet, qin artists never imitated them. They preferred to use singular notes and long notes, and use rhythm and phrasing to bring people into an artistic space moving from ‘real to surreal, far to near’. This blank space is the core of guqin aesthetics.”

“We cannot stop progress in any form, but someone has to guard its vitality, its essence.” He said with conviction: “In future, they will say during that time, there was someone who was doing that work.”

Kee’s mentor felt Kee’s transcription was “random”, where no one could tell whether it was correct, while real transcription should be a scientifically-grounded collective effort with discussion and validation.

“Random” versus “scientific”

Kee once had a frank, in-depth discussion with a mentor about “that work”. Kee’s mentor felt Kee’s transcription was “random”, where no one could tell whether it was correct, while real transcription should be a scientifically-grounded collective effort with discussion and validation. Kee does not deny this but admitted: “In the circumstances, I can only adopt a ‘random’ approach and explore, then publish my findings as an open-ended starting point.

“Over 170 ancient scores survive, but only a few have been truly studied systematically. It is an extremely lonesome and tedious task; almost nobody wants to do it. Where would I find a dozen people to sit with me and transcribe? In the past when Master Guan Pinghu was transcribing, who accompanied him?”

Kee agreed that “scientifically-grounded transcription” is the right way to go, but at the same time he felt that such a collaboration is not restricted by time and space, and is even a cross-generational accumulation; it would take the efforts of at least three generations to thoroughly research these ancient scores. He called his Interpretation of Handbook from the Great Restoration Pavilion merely a starting point, a reference for future generations that could even be overturned, and said his work was just “another drop in the ocean”.

Today, Kee still lives away from the crowd, not bothered by fame and fortune. “I don’t like over-promotion and networking, or joining in meaningless performances and events, racking up countless small successes just to build up to major failure in life.”

“The scores alone cover 500 to 600 pages. For each piece, I write how to learn it, and record my own learning experiences.” — Kee

Perfecting one single work

Kee is currently writing a book Qin Scores of the Streams and Mountains (《谿山琴谱》, Xishan Qinpu). This is not just a collection of qin scores, but a culmination of Kee’s decades of practice, teaching and thoughts on the qin. “The scores alone cover 500 to 600 pages. For each piece, I write how to learn it, and record my own learning experiences.” There are QR codes to videos of Kee playing these pieces; the book also includes selected commentary from his teaching, as well as his reflections on issues like guqin innovation. Kee hopes to finish writing the book within two years.

“I’m 56 years old this year. If heaven permits, I hope to spend my years from 58 to 65 revising my Interpretation of Handbook from the Great Restoration Pavilion.” He said: “I was very naive. When I first started to transcribe, I thought there were over 170 ancient scores beginning with The Mysterious and Marvellous Tablature, and I would transcribe them one by one and see how many I could finish. Later, I realised it’s not about building quantity, but more like Cao Xueqin when he wrote Dream of the Red Chamber, putting one’s lifetime of effort and ability into perfecting a single work.”

The saying ‘harmony is the prime focus’ does not mean to dazzle with skills and win adulation, but to seek inner harmony and balance. Only by clearly understanding that playing the qin is for self-cultivation can our hearts gradually erase restlessness.” — Kee

At the same time, he has infused his pedagogy with tools of the digital era. At the online Xishan Qin College where he teaches, he promotes digital applications and online courses (zhiyuantang.com.cn), encouraging students to practice consistently with “check-ins” while advocating proper qin education values.

“The author of Handbook from the Great Restoration Pavilion, Xu Shangying, says in the preface of Qin Matters of the Streams and Mountains (《谿山琴况》, Xishan Qinkuang): study the ancient sages, understand creation, be at peace with divinity, and manage oneself, so as to manage others.” Kee added: “The guqin, as an instrument for self-cultivation, is meant to manage the individual, before getting over oneself and others. The saying ‘harmony is the prime focus’ does not mean to dazzle with skills and win adulation, but to seek inner harmony and balance. Only by clearly understanding that playing the qin is for self-cultivation can our hearts gradually erase restlessness.”

20 ancient qins exhibited

In line with the beauty of “blank space” in qin music, Kee said what he cares more about at present is the “blank space” of his life; to leave for future generations some references and evidence. The Elegant Sounds: Music, Craft, And The Literati exhibition at the Asian Civilisations Museum is Kee’s heartfelt cultural contribution to his homeland.

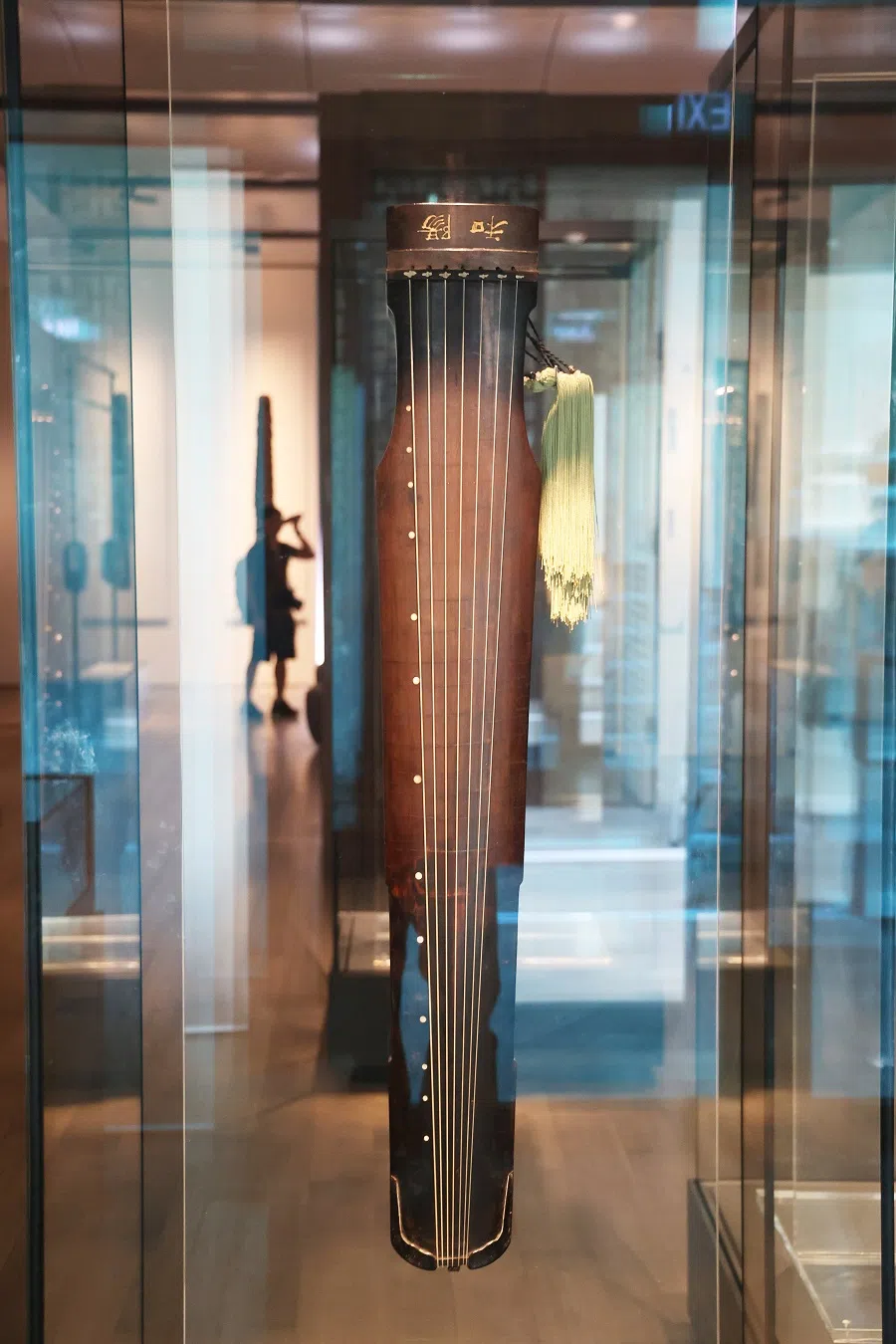

At the entrance to the exhibition, the first items seen are five guqins from the Ming and Qing to the Northern Song periods. One is dubbed Yang He (阳和, lit. sun peace) made by Ming dynasty qin artist Yan Tianchi, the founding father of the Yushan School. This qin is part of Kee’s collection in his Tampines flat, and it carries his deep affinity and emotion for the qin. Another qin from the Northern Song dynasty, with more than a thousand years of history, lets one feel that the days of a thousand years ago are near at hand.

This exhibition features 20 ancient qins, with five on rotation every six months. The hall also showcases 24 newly crafted qins by contemporary guqin craftsman Ning Qunhui. The qins vary in style, including “Zhong Ni” (仲尼, an alternative name for Confucius), “Banana Leaf” (蕉叶) and “Sunset” (落霞) styles. Ning commented that these historically-inspired styles not only exhibit rich aesthetic value, they also produce unique tonal qualities due to differences in the resonator box structure.

The exhibition also presents several paintings featuring literati related to the guqin, showing its symbolic significance in the literary spirit. For example, the Bo Ya Painting depicts the story of the confidants Bo Ya and Zhong Ziqin, with the qin symbolising a medium for spiritual connection; Pu Ru’s An Imitation of Song Dynasty Landscape and Pu Jin’s Misty Rain in Xiling as well as other elegant landscape paintings reflect the literati’s idealistic pursuit of a natural and tranquil life.

Kee expressed a wish to the museum organisers that the collection of guqins should not merely be confined to storage, but should be frequently exhibited — even loaned to suitable individuals for recording and performance, allowing the qins to truly “speak...

To deepen visitors’ understanding and engagement, the exhibition has designed several interactive experiences. Visitors can listen to Kee playing on each qin by scanning QR codes, and appreciate the guqin’s delicate and wistful sound. The Sound of the Qin digital interactive area features real guqins and a digital instruction system, allowing visitors to learn to read jianzi notation and basic playing techniques by interacting with the screen, and experience the pleasure of guqin performance. There is also a permanent performance space in the exhibition hall, with regular performances to immerse visitors in a scholarly, studious vibe.

During the initial planning of the exhibition, Kee expressed a wish to the museum organisers that the collection of guqins should not merely be confined to storage, but should be frequently exhibited — even loaned to suitable individuals for recording and performance, allowing the qins to truly “speak”, which would be the best way to protect and pass on the tradition. Throughout the process of the exhibition setup, he personally witnessed the staff treating each qin with great care; not just cautiously but also with a sense of reverence, and this meticulousness and respect deeply moved him.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “逆時代修行 為生命留白 古琴博士紀志群堅守雅琴大道”.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)