[Big read] From Nam Tin to Yue Hwa: An heirloom from our forebears

Yue Hwa Chinese Products Building is an iconic landmark in Singapore’s Chinatown. In fact, Yue Hwa, a well-established Hong Kong retail group, celebrated its 65th anniversary last month. But this historic building did not begin life as a department store. How did it end up housing a Hong Kong brand? ThinkChina’s Grace Chong tells the story.

“It was a place where people could see the sea and look far away,” 55-year-old Kenry Peh, fourth-generation descendent and tea man behind Pek Sin Choon, one of Singapore’s oldest tea merchants, told me in Mandarin.

It is difficult to imagine that Peh was actually talking about the Yue Hwa Chinese Products Building in Singapore. But that was in the 1940s, when Yue Hwa was still Nam Tin (南天, “southern sky” in Cantonese) — the tallest building in Chinatown at the time.

“The top of the building made you feel as if you stood at the top of the world,” he added, although he was not the one who had witnessed the magnificent scene first-hand. Those were the stories he heard from his oldest staff and uncle, both of whom were born in the 1920s. He only knew that they were there to deliver tea and so happened to catch a glimpse of the glamour of the place.

It was the first Chinese hotel equipped with a lift and even had the moniker “the Raffles Hotel of Chinatown”.

Not for ordinary people

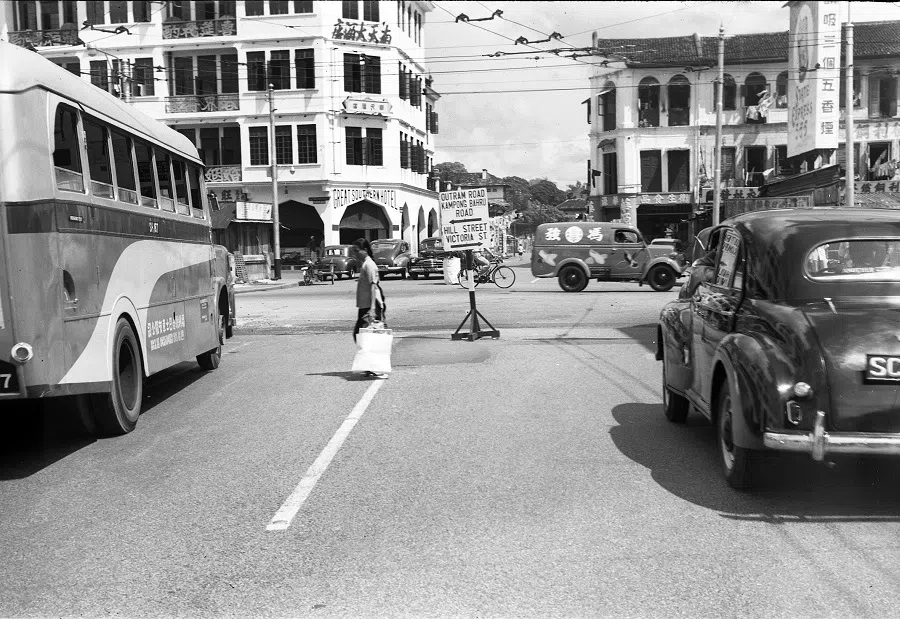

Sitting at the junction of Eu Tong Sen Street and Upper Cross Street, the Nam Tin Building was built in 1927 and initially owned by Lum Chang Holdings. It was designed by colonial architectural firm Swan & Maclaren in the “functional” and “rational” Modern Movement style. Lum Chang Holdings leased the building to several tenants, including the six-storey Great Southern Hotel, which operated from 1936 to 1994.

The Great Southern Hotel, operated by the Cantonese, catered more to Chinese travellers as opposed to Western ones. It was the first Chinese hotel equipped with a lift and even had the moniker “the Raffles Hotel of Chinatown”. Shops were on the ground floor, while the second and third floors were used for hotel accommodation. The fourth floor housed the Nam Tin Restaurant, while the famed nightclub Southern Cabaret sat on the fifth floor. On the roof terrace was a tea house.

The cabaret had a luxurious interior, as described in a Straits Times article published in 1948: “Interior decorations for the cabaret cost over $50,000. Special features are dragon pillars studded with cut glass and the artistically stained illuminated windows depicting famous dancers of various nationalities… [T]he cabaret is an imitation of China’s famed Peking palace… In the centre is a rotating multi-coloured lamp, specially imported from America.”

Information about the restaurant and cabaret is scarce. According to a 1990 article in Lianhe Zaobao by former journalist Au Yue Pak, the cabaret opened much later than the restaurant, which occupied levels four to six and could accommodate up to 130 tables. This layout facilitated a grand “thousand-people banquet”, which was unprecedented in pre-war Singapore.

The restaurant hosted some of the most impressive banquets of its time. As mentioned in Au’s article, when China was fighting the Japanese invasion during WWII, a Chinese military delegation led by military general Shang Zhen visited Singapore in the 1940s. They were warmly welcomed by the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SCCCI) and various other Chinese societies at the restaurant. This grand event, hosted by SCCCI president Lien Ying Chow and vice-president Tan Lark Sye, was celebrated as one of the restaurant’s most magnificent banquets of the pre-war era.

While the Great Southern Hotel was once admired from afar by ordinary Singaporeans, its transformation into today’s Yue Hwa building has made it accessible to more people.

It is no wonder that Peh, hailing from a humble background, has never set foot in the extravagant Nam Tin Building; when he was young, he only visited Chinatown during the Mid-Autumn Festival or during Chinese New Year to buy new clothes, which was a luxury for ordinary households like his back then.

The same goes for 72-year-old Victor Yue, a retiree who has lived in Chinatown all his life.

Upon learning that I was writing a story about Yue Hwa, Yue immediately asked to meet at Nanyang Old Coffee on the ground floor of Yue Hwa for our interview. He lived on Craig Road and later Cantonment Road when he was a kid and had never set foot in Nam Tin Building because there was no reason for him to. “It’s a hotel, you cannot just go in as you like,” he said. “All we only heard is that it used to be a popular hotel as well as a cabaret.”

What he did remember of the area, was his favourite wonton noodles at a coffee shop where a flower shop now sits. To him, the building is “one of the few living heritage” in Chinatown, an “old soul” of sorts, “reminiscent of what Chinatown was”.

While the Great Southern Hotel was once admired from afar by ordinary Singaporeans, its transformation into today’s Yue Hwa building has made it accessible to more people. Yue Hwa came into existence in the 1990s when a group of Hong Kong businessmen acquired the Nam Tin Building.

“By chance, they happened to come to Upper Cross Street and saw this building. They said, ‘Okay, Chinatown is quite a nice area,’ and decided to purchase this building...” — Jacob Yu, third-generation director of Yue Hwa (Singapore)

From Nam Tin to Yue Hwa

In 1993, Hong Kong businessman Yu Kwok Chun bought Nam Tin Building for S$25 million (US$18.45 million) and converted it into Yue Hwa Chinese Products. In fact, Yue Hwa is a well-established retail group in Hong Kong that offers quality Chinese products. Established in 1959 in Hong Kong, the company now has four stores in Singapore (Chinatown, Serangoon, Jurong and Yishun).

The Great Southern Hotel officially ceased operations in 1994, and renovation works for Yue Hwa cost another S$25 million before the department store finally opened in 1996. In an interview, Jacob Yu, third-generation director of Yue Hwa in Singapore, told me a rather amusing story about how a group of Yue Hwa directors — Yu Kwok Chun, Yu Pang Chun and Yu Choy Chun (his father) — had travelled around Singapore in a taxi to look for a place that they could turn into a department store.

“By chance, they happened to come to Upper Cross Street and saw this building. They said, ‘Okay, Chinatown is quite a nice area,’ and decided to purchase this building. This was the only one within the budget and in a good area suitable for our products,” he recalled.

Jacob joined Yue Hwa (Hong Kong) in 2010 and came to Singapore in 2013. He thinks Yue Hwa fits into the Chinatown landscape because the company wants to “proliferate all the good things from China”. Since Chinatown is also a niche area, “we want to attract people who want to create that engagement of all things Chinese”.

“... Culture is a tough business, a very niche business… Selling culture won’t make money, but it’s part of our mission to proliferate that culture.” — Yu

Each of the six storeys in the building has a distinct theme: the first floor focuses on health and wellness with skincare, medicine and nourishment products; the second floor offers modern living essentials including fashion and household items; the third floor showcases Chinese antiques and hosts cultural workshops and a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner. The fourth floor houses a popular supermarket, the fifth floor specialises in Chinese furniture and the sixth floor features a restaurant. During my tour with Andrew Goh, Yue Hwa’s marketing manager, I was shown each floor and even got to see the preserved original balcony features at the rooftop restaurant.

Jacob believes that one of Yue Hwa’s major selling points is its focus on Chinese culture. “You seldom see a department store specialising in culture. Culture is a tough business, a very niche business… Selling culture won’t make money, but it’s part of our mission to proliferate that culture,” he stressed.

An Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) spokesperson told me that the Yue Hwa Building has been conserved as part of the Chinatown Historic District since 1989. Extensive efforts were made to retain and restore the original features of the main building from the 1930s, including balconies, brackets, cast-iron arches and other architectural elements.

“The new extension at the rear is designed to harmonise with the existing building and yet bear its own distinctive contemporary stamp. The challenging project, involving old and new buildings with adaptive reuse was awarded an Architectural Heritage Award in 1997,” the spokesperson pointed out.

Doing business in a conserved building: boon or a bane?

But doing business in a conserved building has its unique challenges, as Jacob pointed out. The original facade, including its colour, must be maintained, requiring repainting every five years. However, the paint texture chips easily, posing a significant issue. Moreover, under URA guidelines, only a limited selection of paints is permissible, adding to the constraints.

During the department store’s extensive refurbishment with construction engineering company ISG in 2019, Jacob and his team worked closely with URA to find out what they could and could not do.

“We were restricted from placing anything within one metre of the windows — inside [the building] — and that limited the layout,” Jacob explained. “Many windows, balcony windows and doors can’t fully close, contributing to noise issues. To manage humidity, we’ve also installed dehumidifiers throughout the building,” he added.

But the real challenge came when they wanted to install an escalator between levels five and six of the building, which were previously linked by lift and stairs.

Since the facade of the building cannot be touched, how could they bring two sections of a large escalator into the building? “We had to drop it in from the ceiling. So again, without touching the conserved building, we removed the roof of the new wing, and used a crane to drop in the escalator,” Jacob recalled.

But Jacob believes Yue Hwa can do more to promote Chinese culture, given its prominent location at the cross junction of two of the busiest roads in Chinatown. However, due to heritage restrictions, the store cannot advertise on its building facade, which directly affects traffic and business. Jacob noted, “It’s very difficult to draw a crowd in without advertising on the facade. We’re only allowed to do so during festive seasons.”

The shell is conserved, but what about the inside?

Given the emphasis on preserving the facade of conserved buildings and less attention on interior modifications, how can owners maintain the building’s inherent spirit and original ambience in line with URA guidelines?

Ho Weng Hin, founding partner of architectural conservation specialist consultancy Studio Lapis, told me that it is indeed easier said than done, especially when it comes to “adaptive reuse”, which means that the building experienced a change of use and ownership.

While the conserved building now houses Yue Hwa, its predecessor, the Nam Tin Building, was constructed during Singapore’s modernisation period. While many assume Singapore only began modernising after gaining independence in 1965, Ho clarified that this was not the case. Despite the perception that little construction was done in Singapore during the interwar period from 1919 to 1942, Ho was amazed by how cosmopolitan and progressive Singapore was shortly after the First World War.

Ho noted that Singapore had built many buildings by the 1930s, “most remarkably” ports, the Kallang Airport, Clifford Pier and the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station. “And Nam Tin was one of those buildings that was built in that era of cosmopolitanism and prosperity,” he pointed out.

“This place is very fascinating because that’s where the ordinary masses came together with this well-heeled crowd, and they kind of exist side by side.” — Ho Weng Hin, Founding Partner, Studio Lapis

‘Authentic’ Chinatown

Ho said that at the time, the Nam Tin Building, with its well-heeled clientele, formed an interesting contrast with the buildings surrounding it, especially the People’s Park Market. “This place is very fascinating because that’s where the ordinary masses came together with this well-heeled crowd, and they kind of exist side by side,” he mused.

Even today, he sees significant potential for synergy between Yue Hwa, The Majestic and the People’s Park Complex, given the charm of the city block. “You literally see different eras of Singapore history co-existing in the entire area… It’s like chapters of the Singapore story unfolding, and also some kind of social continuity with the burned down original People’s Park Market… And architecturally, they are very distinctive,” he shared.

To him, this city block represents a “bold urban renewal vision of Singapore”. “It’s like a microcosm, and it’s very meaningful. In fact, there are many people who feel that this part of Chinatown is the ‘authentic’ Chinatown today,” he added.

Keep the building first

Given Ho’s expertise in conservation and advocacy work, I asked him to evaluate the conservation of the Yue Hwa building. At a time when much of the street scenes that marked the late 1980s and early 1990s were erased due to urban renewal efforts before URA started the conservation programme in 1989, Ho thinks that it is “quite remarkable” that the Nam Tin Building got to stay.

“I always think of it as the parallel to the Capitol cluster. You also have a prominent road junction — this one is Upper Cross Street with Eu Tong Sen Street — a street junction with a commercial building and a theatre. It’s very similar. It’s really a prime location for urban renewal. So they escaped urban renewal and then they were identified as important places to retain along the street so that it’s still recognisable as a historic neighbourhood,” he noted.

But he also reminds us that the conservation of the building has to be understood in “the context of those times”. Back then, the priority was to first ensure that the building did not get demolished. Then came the need to make it commercially viable so private developers would want to take over. He explained, “If you are too strict about what you can or cannot do... you probably won’t find many people taking it up.”

... the most important thing to have in mind is “a sense of custodianship” — it is remembering what our forebears built, along with their aspirations and achievements, which we are the inheritors of. — Ho

So then, in the case of Yue Hwa, Ho noted that the inside was gutted out because it was not the priority back then. And because of this degree of flexibility, he considers the conservation work “interventionist”, which reflected the constraints of those times. Notwithstanding, he believes that more can be done in terms of “heritage interpretation”, which means looking beyond just keeping the building itself and going the extra mile to help people understand the stories behind those buildings, especially the ones that experienced a complete change of use.

An heirloom

At the end of the day, Ho reminds us that the most important thing to have in mind is “a sense of custodianship” — it is remembering what our forebears built, along with their aspirations and achievements, which we are the inheritors of.

But it is also important to note that it is not just about the sentimental value of the buildings. There is a “scientific process of evaluating why certain things are significant” — with today’s level of technical excellence, it is no longer about what can or cannot be done but “about what is right and appropriate”.

While I do not visit Yue Hwa as often as I did when I was younger, walking past the building always reminds me of the fun I once had inside with my popo. I guess this is what buildings do to people, right?

But who makes the call anyway? “The ideal scenario is that it should be a collective decision if the building has public significance,” Ho pointed out. “In a mature and democratic society, decision making should be a process of consultation and negotiation.”

Buildings are not just made up of cold bricks; they contain warm and cherishable memories. “The idea of heritage is intergenerational transmission — you pass it down from generation to generation like an heirloom,” Ho said.

**************************

Writer’s note: what the Yue Hwa building means to me

I have always known the building at the junction of Eu Tong Sen Street and Upper Cross Street to be Yue Hwa Chinese Products. I used to frequent Yue Hwa a lot when I was younger. I lived with my grandparents when I was in primary school and my grandmother (popo) would bring me to Yue Hwa on the weekends. It wasn’t refurbished at the time but I remember feeling like a kid in a candy store each time I visited, mesmerised by all the delicate and exquisite handmade pieces they had to offer.

I would always ask popo to buy something for me, and she always obliged. I remember one of my favourite buys was a traditional Chinese-style pink and blue-beaded shoulder bag with flower motifs. I was so happy with my bag that I would sashay down the living room at my grandparent’s house, asking that everyone watch me carry my beloved bag.

Yue Hwa (裕华) actually means fuyu zhonghua (富裕中华, make China prosperous). This has always been the brand’s mission and vision. Although I had no part in the history of the Nam Tin Building or the Great Southern Hotel, Yue Hwa does have a special place in my heart. While I do not visit Yue Hwa as often as I did when I was younger, walking past the building always reminds me of the fun I once had inside with my popo.

I guess this is what buildings do to people, right?