Creative adaptations of Chinese orthography

Academic Lian-Hee Wee and researcher Tommy Wong observe that while traditional Chinese characters and simplified Chinese characters are taught in schools depending on government policies, the stenography of kitchen workers, pawnshop accountants and even musicians remain marginalised. This is a pity as their stories provide details missing in the more common politico-economic histories of textbooks.

From the varied orthographies of pre-Qin China to the highly standardised simplified Chinese characters (jiantizi) today, one can see the ebbs and flows of how users negotiate established norms. For instance, the character 眀 (ming) “brightness” was written with a 目 “eye” radical until Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋) decided on 明 to name his dynasty. Even then, ancient calligraphers continued to use the radical 目, as is evidenced in how the Ming dynasty literato Wen Zhengming (文徵眀) wrote his name.

Historical orthography is now the province of pundits. By and large, students follow the dictates of authorised standards. However, more pragmatically driven users will fashion orthographies to fit actualities in the lower rungs of society. Their story, unsanctioned by authorities, is often unheard. While traditional Chinese characters (fantizi) or jiantizi are taught in schools depending on government policies, the stenography of kitchen workers, pawnshop accountants, and even musicians remain marginalised. But their stories provide details missing in the more common politico-economic histories of textbooks.

By devaluing the item in writing, the pawnshop gave itself wriggle room should they fail to reproduce the item undamaged when claim is made.

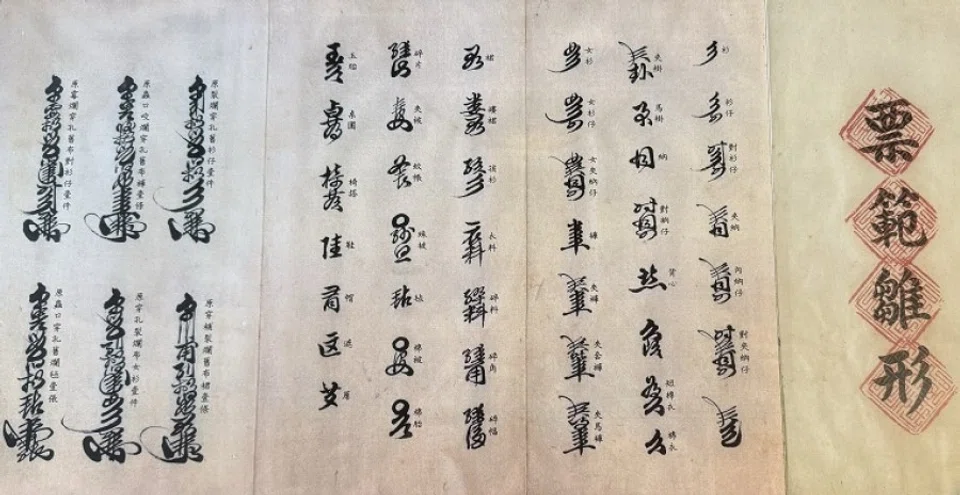

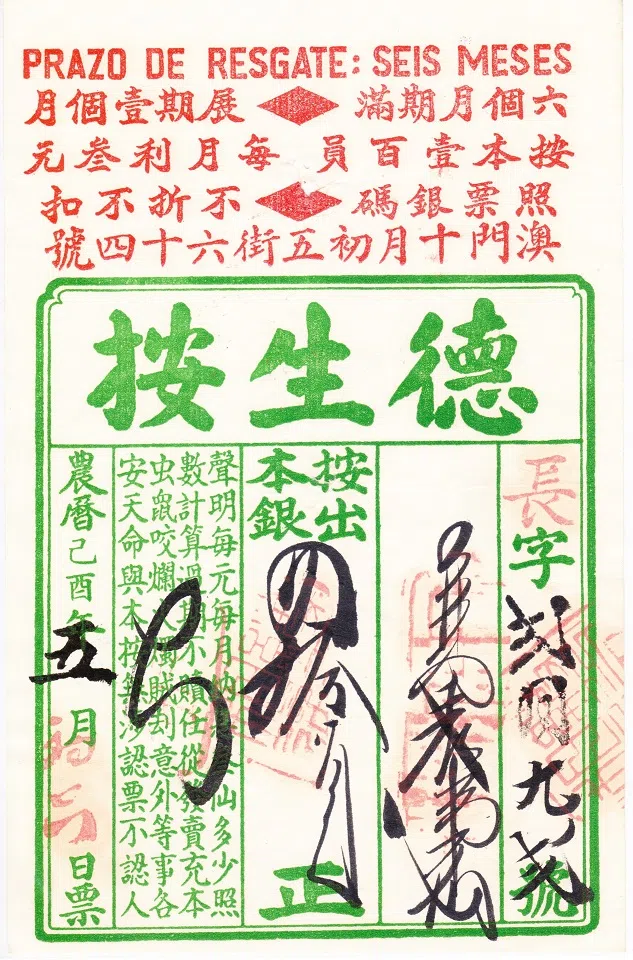

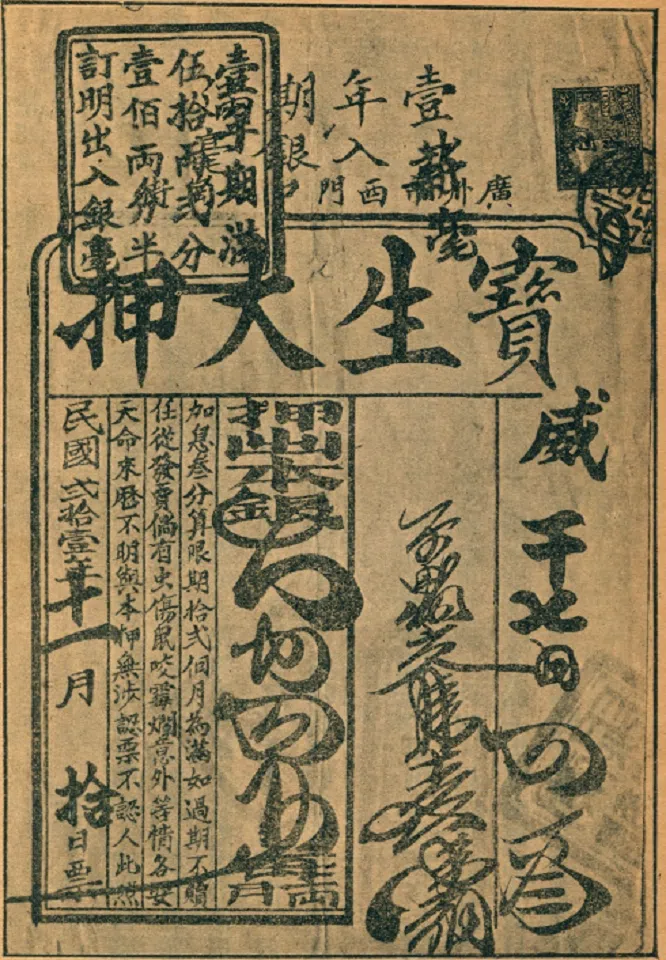

Pawn tickets: preventing forgery and theft

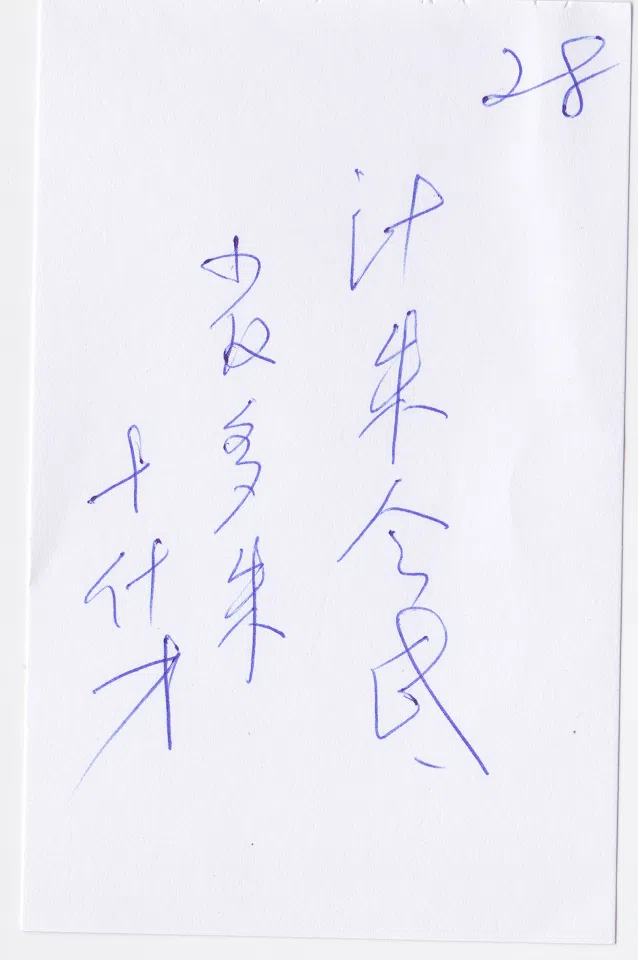

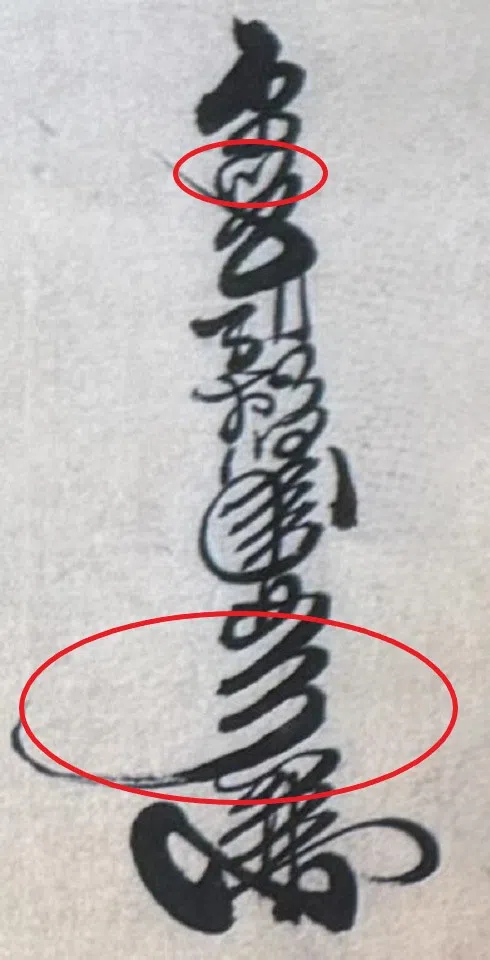

Consider for instance, this pawn ticket from 1969, Macau. It encapsulates both an accounting system and also security measures. The cryptic writing was known usually only to those in the trade. In a lesser way, it protected the ticket holder as the cryptic writing might frustrate petty thieves hoping to steal the ticket and claim a valuable item at a discounted price. There is also something more clandestine going on. These cryptic descriptions usually downplay the quality of the item. The watch here was probably gold and functional, but was described as copper and useless. By devaluing the item in writing, the pawnshop gave itself wriggle room should they fail to reproduce the item undamaged when claim is made.

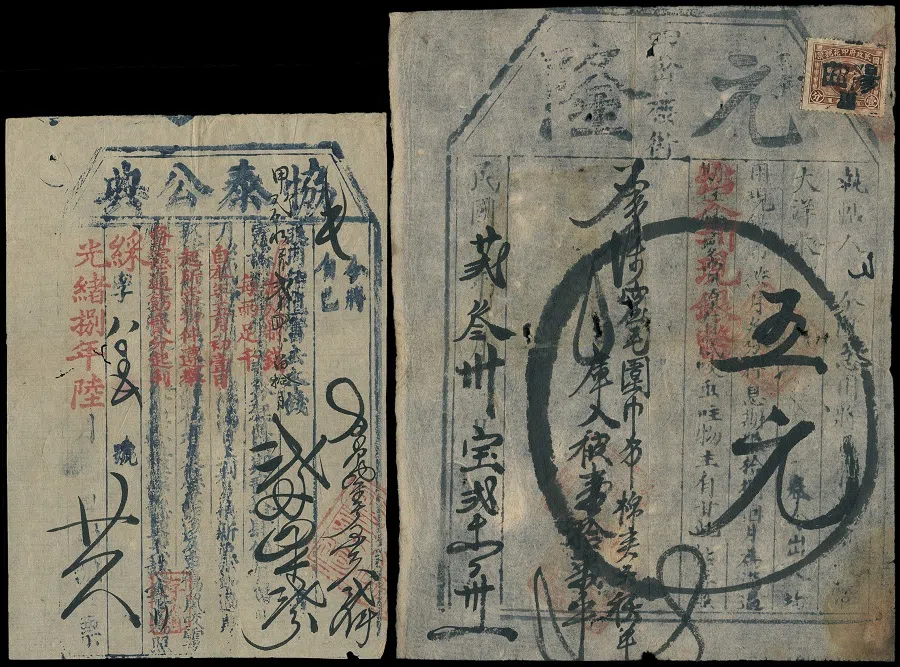

(Left) Shanghai, 1882. Blue columns from right: (i) pawned item, (ii) pawned amount (iii) ticket number.

(Right) Shanxi, 1933. Blue columns from right: (i) pawned amount, $5, (ii) pawned items: scarf, cotton jacket, and blanket, (iii) date. (John Bull website)

The pawnshop is effectively a kind of pauper’s bank for small item mortgages, and security is important. From this ticket alone, we can see three measures. The ticket is numbered to match the ledger kept by the pawnshop. The red seals are property of the pawnshop and stamped only at the point of issuance. Finally, there is the cryptic writing. All these converge to prevent forgeries and theft. Further insurance is provided by the disclaimer printed smaller in green. Such pawn tickets were in use across China.

... the motivation for kitchen stenography is transparency and speed rather than discretion.

These tickets show how things were valued in the past, and make for educational comparison with antiques today. A painting or earrings worth little then may now be featured in high-end auction houses

Eatery order scrawls: transparency and speed

Accountants at pawnshops would have had some schooling, so their invention of trade-specific stenography is hardly surprising. Compare this with the kitchen stenography used among low-end eateries. Both scripts can be seen to be created based on the same principles, but the motivation for kitchen stenography is transparency and speed rather than discretion.

Imagine a Hong Kong caa caan teng (茶餐廳) or a daai paai dong (大排檔) stall during lunch hour. In 90 minutes, wait staff would have served about 200 customers that came in waves as the place probably seated only 50. There will be another line of perhaps 200 takeaway orders. Orders can be quite complex. A noodle stall, for instance, would have seven noodle options (thin egg noodle (幼麵), flat egg noodle (粗麵), pre-cooked thick egg noodle (油麵), thin rice noodle (米粉), flat rice noodle (河粉), yi noodle (伊麵), and of course without noodles (淨食), which may be served in soup or tossed.

The main principle underlying the kitchen stenography is a combination of homophones and abstractions of distinctive graphemes in Chinese characters.

Compounded with an assortment of usually 25 topping options, such as fishballs, wantons, beef briskets, etc., a waiter would have to deal with some 36,750 (=2*7*(25C1+25C2+25C3)) possible unique orders, assuming up to three toppings. That is just the basics, because there would be other customisations related to condiments, sauces, side dishes and drink choices, reaching a staggering three million unique orders for a typical noodle shop. Strangers would share tables, so one needs to improvise table numbering as customers flow in and out. Wait staff (usually two or three) must ensure clear communication with the kitchen to accurately process and deliver each order while being super quick in taking orders. Prior to QR codes for ordering, the solution was stenographic writing.

The main principle underlying the kitchen stenography is a combination of homophones and abstractions of distinctive graphemes in Chinese characters. The result is a highly productive system that can encode any new dish that comes into the menu. This same wisdom underlies the pawnshop cryptography.

Cryptic script and the ingenuity of the Chinese

These examples naturally lead one to contemplate other cryptic Chinese scripts that would include musical notations such as the guqin tablature, and writings of marginalised groups such as the famous nüshu (女書). These and many others have received varying amounts of attention and priorities in preservation. The two presented here, however, enjoyed no such favour. Nonetheless, they present to us the ingenuity of the common folk beyond the scope of standard Chinese. Their stories are part of the Chinese heritage that one should not disregard too carelessly.

Already, these cryptic writings reveal to us the systematicity in grapheme extraction and the use of homophones. Had the jiantizi movement not happened, simplification of orthography would still be driven by very real life needs. Without institutional reins, simplification would have been diverse, varied, vibrant, but systematic too, as our two examples here show. Should one critique kitchen stenography or pawnshop cryptography as corruptions of standard writing, one too must bring that critique to the jiantizi system. Conversely, a staunch supporter of established writing institutions like fantizi should critically ask if innovations to writing are all bad. It may be instructive to ponder how strictly one should adhere to dictionary standards (jiantizi or fantizi, regardless) as bastions of tradition.

Consider the new worlds of written expression created when King Sejong created the Korean hangul in the 15th century by encoding articulatory phonetic information into Chinese-styled ideogrammatic writing. Even earlier, the Japanese hiragana, invented by the creative women during the Hei’an period who made radical adaptations of the Chinese script from which their cultured men dared not stray. That innovation gave us a shiny gem that is one of the world’s first full-length novels, Genji Monogatari. The full tapestry of Chinese expression is much more variegated than jiantizi or fantizi; the full potential of the orthography may yet have been explored.