Finding Pan Shou: A Singapore calligrapher’s grave in Perth

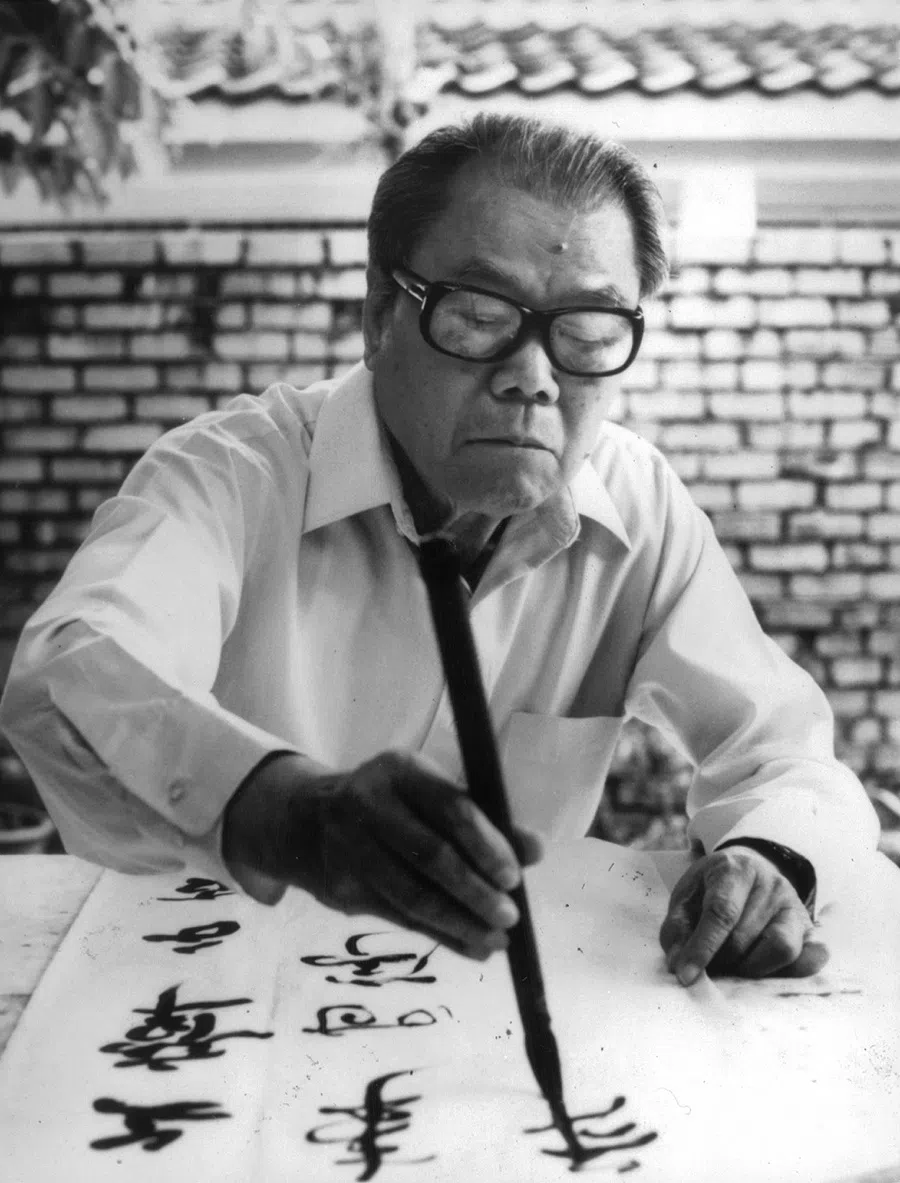

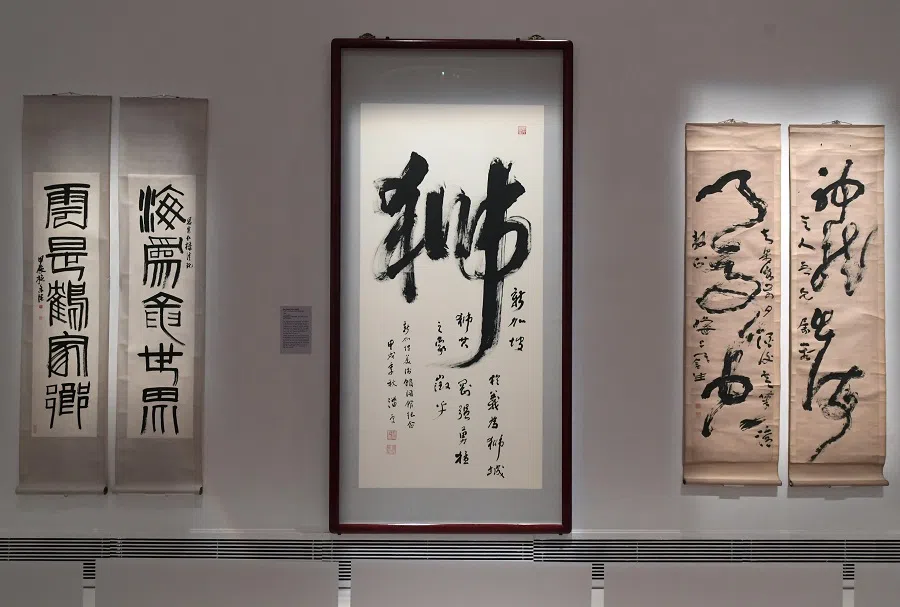

History enthusiast Zhao Baozong chronicles his journey to pay respects to notable calligrapher and poet Pan Shou, who had called Singapore home but found his final resting place in Perth, Australia.

On 19 August, my wife and I visited Pan Shou (潘受)’s grave in Perth, Australia.

The ancient Karrakatta Cemetery was especially quiet after the rain. With two bouquets of wild chrysanthemum — one white and the other purple — we paid our respects to this revered cultural icon who was born in China, lived in Singapore and laid to rest in Australia.

Started from a 2015 article

It has been 25 years since the notable poet and calligrapher passed away in 1999. In a 2015 article titled “Pan Shou Rests in Perth” (《潘受长眠珀斯》), Lianhe Zaobao reported that Pan, along with his first and second wives, were buried under a tree at Perth’s Karrakatta Cemetery. Photographs of the tombstone and its inscription were provided by Pan’s daughter, Pan Xiao Fen. In the nearly ten years since, there have been no public reports about the condition of Pan’s grave.

I started gathering information last year to write a biography and chronicle of Pan. At the start of the year, I felt it was apt to visit his resting place and thus began making preparations. The 2015 Lianhe Zaobao article mentioned the name of the cemetery and the specific section of the cemetery where the grave is located. Since the information was provided directly by Pan’s daughter, I took it to be accurate.

However, I could not find any online information about the Lance Howard Rose Gardens in the cemetery. I contacted the author of the article, Lianhe Zaobao journalist Chia Yei Yei, and she confirmed that she had never been to the cemetery and that the photographs were provided by Pan Xiao Fen to Yu Li Pin, a former pilot who had known Pan Shou for two decades, and then passed to the newspaper by Singaporean artist Koh Mun Hong. They, too, had never visited Pan’s grave in Perth before. My efforts to contact Pan Xiao Fen also led me to a dead end.

Fortunately, after arriving in Perth, I managed to contact a Singaporean couple, Mr and Mrs Goh, long-time residents of the city who were in contact with Pan’s descendants.

Through them, I found out that Pan’s son, Pan Soo Yeng, had passed away a few years ago. The enthusiastic Mrs Goh even called Pan Soo Yeng’s widow, Selina Pan, to tell her about my trip to Perth.

Selina is not proficient in Chinese and was also down with Covid-19 at the time. Given her age, it would also be difficult for her to accompany me to the cemetery. But she roughly described the location of the Pan family’s gravesite and advised me to seek assistance from the cemetery office using Pan Soo Yeng’s name.

It was already 4pm after we spoke on the phone. Daylight hours are short in Perth and the gloomy sky made it seem as if evening had already come. Although the Gohs have never visited the Pan family’s gravesite, they knew that it would be difficult to find without a specific location given how big the cemetery was.

Although the Karrakatta Cemetery’s office was closed on a Saturday, the Gohs insisted on accompanying us there. We found the office near the main entrance, and I got a hold of a map from the information board outside — I was left confused after looking it over.

The map listed at least three “rose gardens” — Rose Gardens, Harmony Rose Gardens and Centenary Rose Garden — as well as the Lance Howard Memorial Gardens. But none of them matched the one mentioned in the Lianhe Zaobao article.

Mr Goh advised me to come early next Monday to avoid the crowds attending funerals, and pointed out where I should park and how to ask for information.

It is also the final resting place of notable figures from politics, academia and the arts, as well as ordinary citizens, and also 111 soldiers who fell in the First World War and 141 in the Second World War.

Using clues to find my way

At 9am on Monday, my wife and I arrived at the office of Karrakatta Cemetery with fresh flowers in hand. I told the staff that I had specially come from Singapore to pay respects to a Singapore master artist. She kindly accepted the piece of paper with “Pan Soo Yeng” written on it and looked up the name on the computer.

After a few minutes, she confirmed that the gravesite is located at Lance Howard Memorial Gardens, although there was no specific number or symbol to pinpoint its location. She handed me two maps and I left confidently, because finding my way using visual clues is my forte.

Based on online information, Karrakatta Cemetery is the largest cemetery in Western Australia and located seven kilometres west of downtown Perth. First opened in 1899 and boasting a history of 125 years, it is just a few kilometres away from the Swan River and the Indian Ocean coast, sprawling over 98 hectares of land.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been laid to rest in the cemetery, including West Australians as well as the deceased from other countries and regions. It is also the final resting place of notable figures from politics, academia and the arts, as well as ordinary citizens, and also 111 soldiers who fell in the First World War and 141 in the Second World War.

Spring had just begun in the southern hemisphere, and Perth, located by the Indian Ocean, was also in the rainy season, so rain was visibly looming.

There was no chatter from passersby. The air was moist and the land was serene.

We entered the cemetery via “Drive Way”, flanked by lush green trees, including Leyland cypress, Mediterranean cypress and tropical palms. It was my first time visiting a church cemetery, and I was a little apprehensive.

The cemetery is huge, beyond what I had expected; and driving is permitted within the grounds. After passing the Rose Gardens in front of Norfolk Chapel, there is a large gravesite on the right, with headstones on most graves, marked on the map as the Roman Catholic section.

After passing the Centenary Rose Gardens, I spotted Serenity Gardens on the right. Make a right and drive straight for another 300 metres and we would arrive at Lance Howard Memorial Gardens. Sure enough, in the open area before reaching the intersection, I saw a large wooden sign that read “Lance Howard Rose Gardens”.

“Pan’s grave should be around here!”

“Look, there’s a huge Eucalyptus tree in the distance!”

The Eucalyptus tree is rather thick, but it did not seem as tall as it had appeared in the photograph published in the newspaper. More than 20 years have passed, and I guess the tree must have aged as well. I gently walked under the large tree and looked down slowly at a flat, rectangular headstone, searching for the letters spelling “PAN”.

It wasn’t it. The second one wasn’t it either... None of the five headstones close to the tree were the right one.

The photograph in the newspaper showed a two-dimensional image, but this was a three-dimensional site.

I quickened my pace, expanding my search area.

The inscription is entirely in English, using the Times New Roman typeface in gold ink. The epitaph was likely engraved using electrical discharge machining.

Laying down flowers

“Here! Dr. Pan Shou!”

A rectangular slab of artificial marble, approximately 5 feet long and 1.5 feet wide, lying about 2 feet above the ground at a slight angle. In the centre of the slab is an embedded bronze epitaph measuring about 1.5 feet long and 1 foot wide, with raised golden edges and a dark brick-red background. The inscription is entirely in English, using the Times New Roman typeface in gold ink. The epitaph was likely engraved using electrical discharge machining.

Pale yellow grass. A few fallen dried leaves.

Three small stone tablets rest beneath the rectangular stone slab. Each tablet measures about a half-foot square, and includes their own epitaphs in the same typeface. From right to left, the inscriptions on the three small stone tablets are “Chen Boon Hwee”, “Cheng Eng Chan” and “Pan Soo Yeng” — Pan, along with his two wives and son, rest here.

I gently placed the flowers before the tombstone, the white bouquet on the left and the purple bouquet on the right, paying silent tribute and reflecting quietly.

The dark clouds drifted away and sunlight streamed down. I took a photograph to remember the moment, with the large eucalyptus tree in frame as well.

Tiny raindrops fell as the wind blew, wetting the map in my hand. I had left my umbrella in the car.

When we returned to the entrance of the cemetery, we saw a funeral taking place. Five long black hearses were lined up, with 200 to 300 guests dressed in black slowly entering, saying their final goodbyes to their loved ones.

Selina thanked us for our sincere remembrance after receiving the photograph I took. She told me that back then, she, along with Pan Soo Yeng, were the ones who relocated Pan Shou and his first wife Cheng Eng Chan’s ashes to Perth.

Although his experiences and career did not have much to do with Perth, his burial there is understandable as his son migrated to Australia and his second wife lived out her final years there.

Why was Pan Shou laid to rest in Perth?

Born in Fujian, China, in 1911, Pan moved to Singapore in 1929 to earn a living. He escaped before Singapore fell in February 1942, and ended up in Chongqing, the wartime capital of China. He returned to Singapore in 1949, and served as secretary-general of Nanyang University (Nantah) from 1955 to 1959.

He was primarily active in China and Singapore in his lifetime, and achieved great accomplishments in cultural education and artistic creation, earning deep respect from the Chinese community. Although his experiences and career did not have much to do with Perth, his burial there is understandable as his son migrated to Australia and his second wife lived out her final years there.

Pan visited Perth nearly ten times between 1983 and 1998. His first trip to Perth was from 26 September to 14 October 1983. He wandered about for about three weeks and composed 14 poems. He had just obtained his Singapore citizenship at the time and this trip to Perth should be his first overseas trip after getting a Singapore passport.

In Perth, his joy was vividly expressed in the “Four Quatrains on Perth” (《珀斯绝句四首》):

“Space gazes at Earth’s autumn, a beam of light pierces the Bull (太空初瞰地球秋,一道光芒射斗牛).

“The world starts to find its way with clues, Perth is in West Australia (世始按图纷索骥,珀斯城在西澳州).“

As explained in the annotation, “The beauty of Perth’s scenery is somewhat reminiscent of China’s West Lake...

In another poem, he compares Perth with Hangzhou, China’s “heaven on earth”:

“As Su Shi’s poems exquisitely describe, the beauty of a woman is displayed whether in the subtlety of light makeup or the richness of heavy makeup (坡仙诗句妙形容,妆抹佳人听淡浓).

“Compared to West Lake’s charm, Perth is only lacking two high peaks (如与西湖相比较,珀斯只欠两高峰).”

As explained in the annotation, “The beauty of Perth’s scenery is somewhat reminiscent of China’s West Lake. The Swan River flows from the northeast, bending westward into the sea. As it passes through the city, the river widens suddenly, resembling a lake rather than a river. The traffic bridge over the Swan River seems to divide it into two, much like West Lake’s inner and outer lakes. In terms of size, it is roughly comparable to West Lake, only regretfully lacking the grandeur of the northern and southern peaks.”

Interestingly, it so happened to be the Double Ninth Festival (重阳节) when Pan, then 73, returned to Singapore. The poet was overwhelmed with poetic inspiration and wrote a poem while on the plane. The poem’s name is rather long: “Counting on my fingers, it is the ninth day of the ninth lunar month today — the Double Ninth Festival. Being 30,000 feet in the air, I cannot be without a poem to honour the ancients.”

The poem itself is not long: “One may lose in many matters but there’s no need to shy away from them; I find enough pride in just one thing. Who in ancient times was like me; able to compose poetry as I ascend into the sky on the Double Ninth Festival.” (输人万事无庸讳,一事居然有足豪。试问古来谁似我,九重重九赋登高。)

On this trip to Perth, Pan came with great enthusiasm and left with great satisfaction.

Perth’s Swan River must have looked as beautiful as West Lake in October, right?

I guess Pan must have liked Perth.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “珀斯谒潘受墓”.