The mask speaks: Unmasking the spirit of Sichuan opera [Eye on Sichuan series]

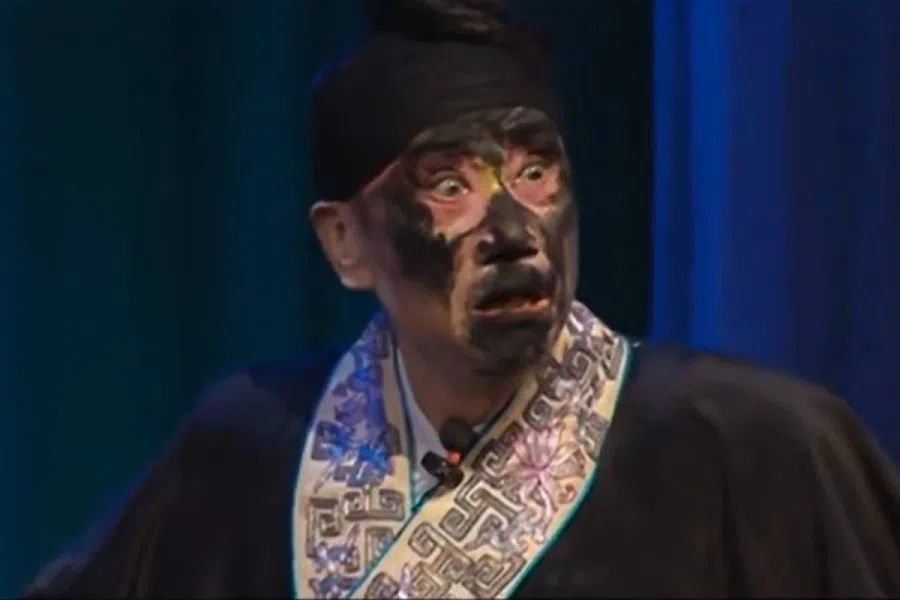

Face-changing or bian lian is commonly seen in Chinese opera, particularly Sichuan opera. A turn of the head or a swirl of a cape is all a performer needs to change their facial appearance in a sleight of hand that happens in the time it takes for the audience to blink. Sichuan academic Yan Pei explains more about this heritage art.

During this year’s Chinese New Year celebrations, London’s Trafalgar Square and Chinatown were vibrant with decorations and festive cheer. The Chengdu Tianfu No. 7 High School Troupe participated in the 24th edition of the “Four Seas Spring Festival — Chinese Stars Shine” (四海同春—华星闪耀) cultural exchange tour. Since its inception in 2001, this event has been a highlight on the official calendars of both the London and British governments.

The northern lion dance troupe brought traditional Chinese lion dance culture to London, while integrating a unique intangible cultural heritage from Sichuan: the art of “face-changing”, or bianlian (变脸). In Sichuan opera, face-changing is a distinctive theatrical technique that vividly portrays a character’s emotional shifts by transforming facial masks.

For a long time, masks were used in religious rituals for witchcraft or sacrificial ceremonies, but they later became tools for dramatic performance on stage.

In fact, throughout the global history of mask cultures, masks have undergone a complete transformation in meaning. As Hans Belting says in Face and Mask: A Double History, “Since the origin of the theater, the mask has been inseparable from its history. Throughout this evolution the mask has been subject to changing interpretations.” For a long time, masks were used in religious rituals for witchcraft or sacrificial ceremonies, but they later became tools for dramatic performance on stage.

‘Face-changing’: the life and emotions of faces

Face-changing comprises three main techniques: “wiping” (抹脸), “blowing” (吹脸) and “pulling” (扯脸), as seen in segments such as the “Three Transformations” (三变化身) scene in Return-to-Right Hall (《归正楼》) and the “Broken Bridge” (断桥) scene in The Legend of the White Snake 《白蛇传》).

In the “Three Transformations”, righteous thief Bei Rong robs the wealthy to aid the poor, and escapes through some deft face-changing of the “pulling” variety. This is a complex technique that involves drawing face masks on pieces of silk, cutting them out, attaching threads to each mask, and then applying them to the face one by one; as the plot unfolds, the masks are torn off one by one under the cover of dance movements.

The “Broken Bridge” scene highlights green snake spirit Xiaoqing’s rage at the mortal man Xu Xian for his betrayal of white snake spirit Bai Suzhen. The actor first turns their face red, then black with their hand — this “wiping” technique involves putting hidden greasepaint on specific areas of the face, which is then dragged or wiped across the face to change its appearance.

This is followed by “blowing” of gold dust or powder. “Blowing” is also known as “blowing dust”, and is only applicable to powdered makeup. “Dust” is prepared beforehand and blown onto oil-coated cheeks, and then “gold powder” is blown to change the face.

In performances like “Punishing Zi Du” (《伐子都》) and “Governing Zhongshan” (《治中山》), face-changing for characters such as Zi Du and Yue Yangzi features the “blowing” technique. Zi Du, a military officer from the Spring and Autumn Period, spirals into a tormented, hallucinatory state after assassinating his superior, haunted by the ghost of the slain commander. In a dramatic face change, Yue Yangzi’s face turns gold and his beard white upon realising he has eaten his son, symbolising profound trauma.

His seven-coloured masks shift seamlessly across his face, mirroring the rippling waves of the river.

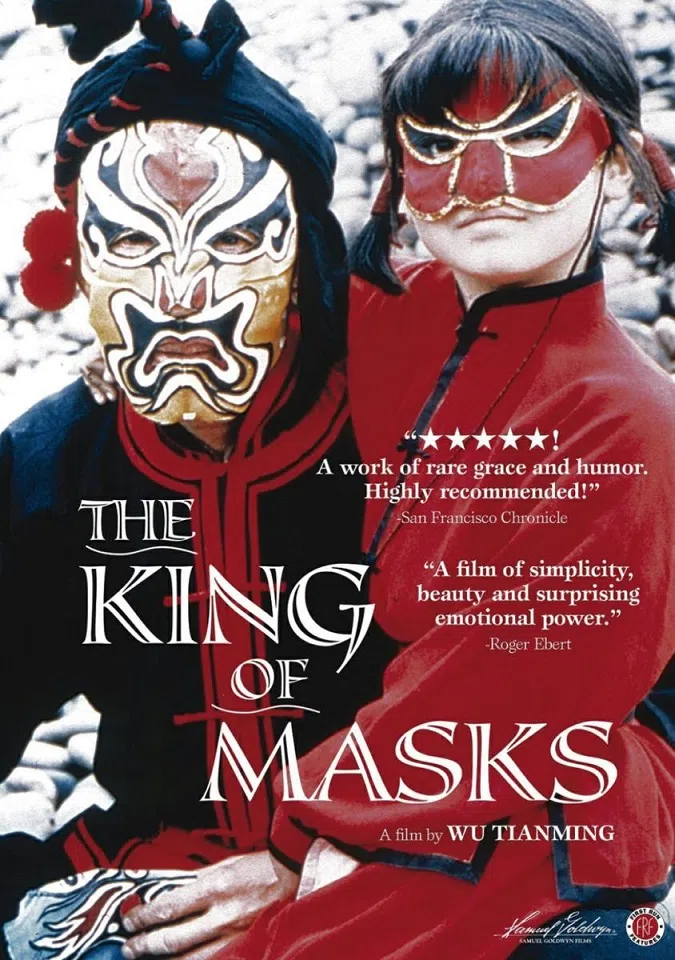

Face-changing is a signature skill of Sichuan opera performers. In the opening scene of the 1995 film “The King of Masks”, directed by fifth-generation filmmaker Wu Tianming and written by playwright Wei Minglun, an elderly face-changing artist known as the King of Masks performs at a Yangtze River wharf. His seven-coloured masks shift seamlessly across his face, mirroring the rippling waves of the river.

Of grassroots and underworld guilds

On the origins of face-changing, Sichuan opera expert Du Jianhua says in A History of Sichuan Opera (《川剧史话》) that during the Qing Xianfeng and Tongzhi periods, Sichuan opera was thriving, with many travelling theatre troupes performing year-round at waterfront docks, moving from province to province, showcasing their skills. Driven by poverty, the actors (troupes) led an itinerant life, known in Sichuan opera slang as “running the banks” (跑滩) — these performers were called “bank runners” (跑滩将).

At the same time, there were also folk acrobatic troupes, who had generally mastered unique skills such as cross-sword fighting, knife-throwing, sword-swallowing, fire-breathing and face-changing, as well as performing traditional magic tricks. Face-changing came about because the “bank runners” were inspired by the “hall performances” (“堂彩”) of the acrobatic troupes. They then used it in the opera “Return-to-Right Hall”, where the outlaw Bei Rong uses face-changing to disguise himself and evade capture, initially appearing in a blue mask, then changing into a red mask, followed by black, and finally into a mask called a “ba’er lian” (霸儿脸, lit. dominant character face), used in Sichuan opera to depict a young, masculine character in his prime. This “triple change” is done with the “pulling” technique, and this scene is known as the “Three Transformations”.

Sichuan’s mountainous terrain and crisscrossing waterways, with its many piers, gave rise to various underworld guilds and associations.

In the Sichuan dialect, there is a saying 袍哥人家,绝不拉稀摆带, to the effect that men of the world (袍哥, pao ge, a reference to secret organisations aiming to overthrow the Qing dynasty and restore the Ming dynasty) are never wishy-washy or sneaky; it means that pao ge deal with the world based on personal connections and integrity. Sichuan’s mountainous terrain and crisscrossing waterways, with its many piers, gave rise to various underworld guilds and associations. Pao ge culture became an integral part of Sichuan’s historical and cultural identity, and a key thematic element in Sichuan opera.

Within the Chinese cultural sphere, the character Guo Jing in The Legend of the Condor Heroes by Jin Yong says: “Minor heroes uphold justice and rob the rich to help the poor; great heroes serve the nation and people.” Many Sichuan opera productions explore such ideals: Return-to-Right Hall features the chivalrous thief Bei Rong; Qin Liangyu (《秦良玉》) features a Ming dynasty heroine who resisted the Manchu invasion; Heroes of the Wilds (《草莽英雄》) celebrates pao ge groups who united to fight Qing forces in the late Qing dynasty; Liu Guangdi (《刘光第》) honours Sichuan-born Liu, one of the six martyrs of the 100-Day Reform movement in 1898; and Peng Jiazhen (《彭家珍》) tells of a revolutionary who sacrificed himself to assassinate a Qing imperial guard leader.

These productions offer artistic reenactments of major events in the Sichuan region, as well as righteous individuals with a strong sense of civic justice and self-sacrifice. Today, pao ge organisations no longer exist, but contemporary Sichuan opera writers have captured the vivid and culturally distinct image of the pao ge figure, such as Shui Shang Piao (水上漂, lit. “Floats on Water”) in Wei Minglun’s The King of Masks, Fifth Lord Luo (罗五爷) in Xu Fen’s Ripples in Dead Water (《死水微澜》), and Chou Hu in Long Xueyi’s Gold (《金子》).

Through artistic transformation, these works preserve Sichuan’s regional trait of valuing change and innovation, while forging a dialogue between traditional underworld ethics and contemporary values through cross-era narrative reconstruction, thus creatively passing on cultural legacy.

Part of street-level and teahouse cultures

Chengdu is itself “a city steeped in tea”. Today, drinking tea, watching Sichuan opera, and chatting — known locally as bai longmen zhen (摆龙门阵, referring to gabbing in a courtyard entrance or 龙门) — are some of the most popular and vibrant forms of street-level culture in Sichuan. Teahouses in Chengdu are ancient and charming, with nearly every street and alley boasting at least one. These teahouses represent the heartbeat of everyday urban life.

A popular local rhyme goes: “Yuelai Teahouse is also a theatre, drums and gongs fill the air with cheer; sip tea, watch a play, munch sunflower seeds — everyone’s a little immortal!”

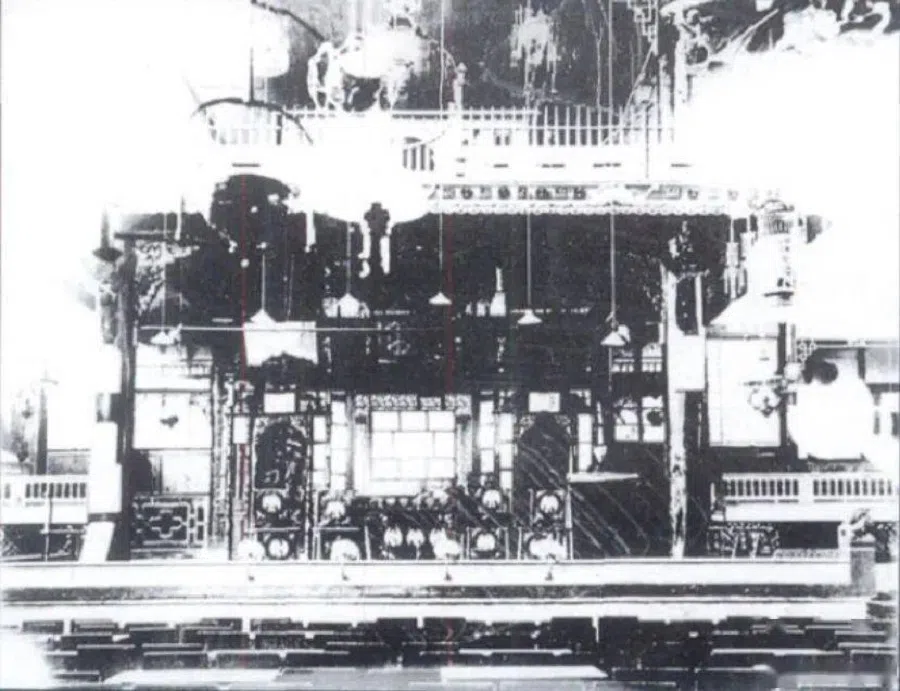

One of the most iconic is Yuelai Teahouse, located on Huaxingzheng Street in Chengdu. Established in the late Qing dynasty, it has a history of over 100 years and is affectionately known by locals as the “cradle of Sichuan opera”, and a Mecca for many opera lovers. A popular local rhyme goes: “Yuelai Teahouse is also a theatre, drums and gongs fill the air with cheer; sip tea, watch a play, munch sunflower seeds — everyone’s a little immortal!”

In modern times, as Western culture and capitalist economics seeped into Chinese society, it had a fundamental influence on local opera in this feudal society. Regional theatre troupes moved from villages and ports into urban centres seeking more frequent performances, and following the trend set by Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou in the late 19th century, Chengdu opened its first permanent theatre in a modern teahouse. Yuelai Teahouse officially opened in 1908, paving the way for permanent opera venues in Chengdu and other major Sichuan cities.

In the old days, many Sichuan opera enthusiasts, affectionately called wan you (玩友, lit. “play friends”, meaning hobbyists), would gather at teahouses and sing Sichuan opera a cappella, known as da wei gu (打围鼓, lit. “beating the circle drum”). Others came to listen to storytelling, light operas, or puppet shows. In this way, teahouses became vital spaces for the preservation and transmission of folk performing arts.

From the days of the Sanqing Hui opera troupe a century ago to the present, the gongs and drums of Sichuan opera have rarely fallen silent in Yuelai Teahouse.

History of masks: ritual to theatre

The Sanxingdui archaeological site in Guanghan city, Sichuan province, is a relic of the ancient Shu civilisation dating from the Neolithic period to the Shang and Zhou dynasties. The iconic gold mask that was unearthed there is regarded as an important symbol of the theocratic nature of ancient Sichuan culture.

They performed in open spaces or on a mat; if the show was at night, the set was illuminated by lanterns, hence the name “lantern opera”.

Since the dawn of civilisation, from ancient Egyptian funerary masks to the bronze masks of China’s Shang and Zhou dynasties, masks have served vital religious and shamanistic functions. Ancient peoples believed that during sacrificial ceremonies, masks endowed shamans with the ability to communicate with deities, creating a spiritual bridge between humans and the divine.

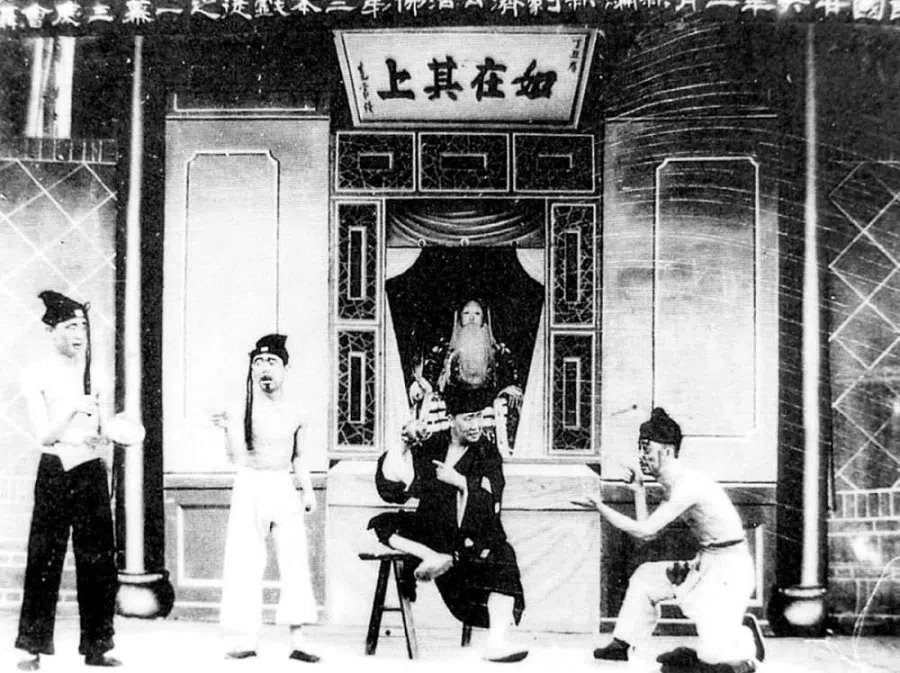

One of the oldest forms of Sichuan opera is northern Sichuan lantern opera (川北灯戏, chuanbei dengxi), which traces its roots to Nuo (傩) opera local to Anhui province. Nuo means to exorcise evil spirits and drive away plagues, and Nuo opera is a form of primitive religious drama performed during rituals and celebrations.

Masks are an important part of Nuo opera, and mostly have to do with religion, and spirits and deities. Performers wear painted masks or lian zi (脸子, faces) according to their roles, categorised into eight types: mo (末, male lead), jing (净, painted-face), sheng (生, male lead, includes mo roles), dan (旦, female lead), chou (丑, comic), wai (外, older male), tie (贴旦 tie dan, secondary female), and xiao (小生 xiao sheng, young male). The performance itself is called tiao nuo (跳傩, lit. “jumping/dancing Nuo”), typically accompanied by drums and gongs.

Lantern opera 灯戏 groups were called doudou ban (逗逗班, “teaser troupes”). In the early days, they consisted of just three members, one of whom would play female dan roles. They performed in open spaces or on a mat; if the show was at night, the set was illuminated by lanterns, hence the name “lantern opera”.

Over time, the use of masks in ritual and religious practices — once intended to “entertain the gods” — has been replaced by theatrical performances in professional theatres meant to “entertain people”.

Characters and their faces

Four character types or roles developed in Sichuan opera: sheng, dan, jing, and chou. Each role is associated with specific facial makeup, known as lian pu (脸谱, lit. face templates).

As Sichuan opera expert Zhang Decheng explains in A Brief Discussion of Lianpu (《略谈脸谱》), “Since it is called a pu (谱, template), it is not random painting on the face, but follows a template.” Specific colours convey the personality of the character — red for Guan Yu, loyal and brave; black for the upright Bao Zheng (Justice Bao); and white for the cunning Cao Cao. Each is given strong character indicators.

As a performing art, face-changing is highly stylised, and has to be in line with the character’s emotional state within a fixed narrative context.

Refined young male roles (文小生, wen xiaosheng) are often frail, studious scholars, where face-changing is used to express shock and fright, such as Wang Kui in A Test Of Love (《情探》) and Shi Huaiyu in Fengcui Mountain (《峰翠山》). Here, face-changing dramatises the fate of men who betray their lovers and are condemned to face vengeful ghosts or the fury of the women they destroyed.

Martial young male roles (武小生, wu xiaosheng) are typically warriors, heroes, or celestial beings. For such characters, face-changing conveys celestial powers or physical injuries, such as the deity Wei Tuo in Jinshan Temple (《金山寺》), young hero Yang the Eighth (杨八郎) in Yumen Pass (《禹门关》), and statesman Lu Xun in The Stone Sentinel Maze (《八阵图》).

Mature male roles (须生, xu sheng) are often middle-aged generals or heroic men, where face-changing reflects tension or anger, such as Zhuge Liang in Empty City Stratagem (《空城计》), and Taoist priest/demon hunter Yan Chixia in Flying Cloud Sword (《飞云剑》).

For female characters (旦, dan), face-changing is used in more unique situations, mainly for roles like ghosts or fox spirits as they transform between spirit and human form by putting on or removing a mask, such as the restless spirit Yan Xijiao in Capturing Zhang the Third Alive (《活捉张三郎》) longing for her lover.

Timeless expressions of fundamental human emotions

In short, face-changing, as a key symbol of Sichuan culture, transforms the sacred symbolism of shamanistic Nuo rituals into an emotional vehicle for secular storytelling through the three techniques of wiping (抹), blowing (吹), and pulling (扯).

As an intangible cultural heritage, the core value of face-changing goes beyond passing on skills, but it can also be a living medium for cross-civilisational dialogue in the context of globalisation. When the northern lion dance troupe incorporated the “pulling” technique into their Chinese New Year performance in Trafalgar Square, face-changing became part of intercultural dialogue.

As part of Sichuan’s cultural heritage, the art of face-changing conveys a deeper message: the essence of mutual learning among civilisations lies not in the search for Eastern exoticism or “Chineseness”, but in recognising the shared, timeless expressions of fundamental human emotions.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)