China’s rail ambitions in Afghanistan may reshape Eurasia

With little fanfare but far-reaching implications, China is stitching together the heart of Eurasia, one rail link at a time. Researcher Genevieve Donnellon-May explores the issue.

On 21 May, the foreign ministers of China, Pakistan and the Taliban-led Afghan administration met in Beijing for a trilateral dialogue, reviving a forum first launched in 2017 and last convened in May 2023. Though the meeting attracted limited media attention, it yielded a landmark agreement: the formal integration of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) with the long-planned but unbuilt Trans-Afghan Railway (TAR).

This agreement to formally link the two strategic connectivity projects signals Beijing’s ambition to transform the Eurasian heartland. While CPEC has primarily focused on infrastructure and energy in Pakistan, its extension into Afghanistan reflects both an economic vision and a push to support Afghanistan’s post-conflict reconstruction and regional integration.

Currently, China is Pakistan’s and Uzbekistan’s largest trading partner. It was also the first country to accept a Taliban-appointed Afghan ambassador, though it has yet to formally recognise the regime.

Estimates suggest the nearly US$5 billion project could cut shipping times from 35 days to 5 days, and reduce costs by 40%; it is expected to carry up to 15 million tonnes of cargo annually by 2030.

The Trans-Afghan Railway (TAR)

The TAR is a bold geopolitical bet by China’s regional partners, traversing some of the most politically fragile terrain in Central and South Asia. If completed, it would be the first direct rail corridor linking Central and South Asia, establishing a strategic land bridge between Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

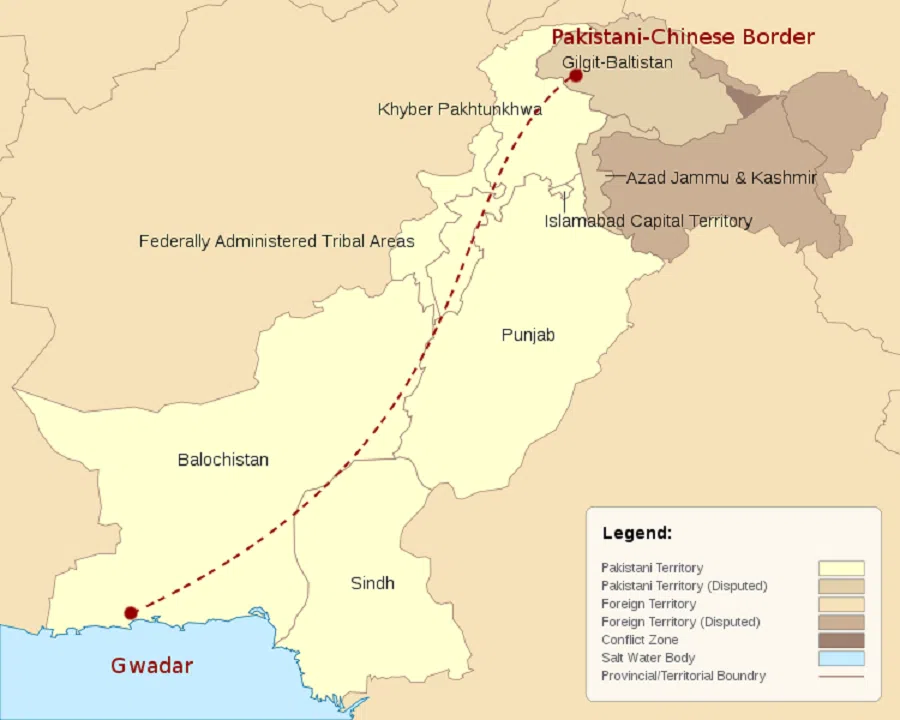

While the final route remains unconfirmed, several proposals have emerged. One leading plan envisions connecting Termez (Uzbekistan) with Peshawar (Pakistan) via key Afghan cities such as Mazar-e-Sharif and Logar. This nearly 600-kilometre rail corridor would give landlocked Central Asian states direct access to the Arabian Sea through Pakistani ports like Gwadar and Karachi, while opening new overland routes for South Asia to reach Central Asian and European markets, bypassing sanction-prone corridors in Iran and Russia.

Estimates suggest the nearly US$5 billion project could cut shipping times from 35 days to 5 days, and reduce costs by 40%; it is expected to carry up to 15 million tonnes of cargo annually by 2030.

Although construction of the route has not yet officially begun, some progress has been made. A TAR coordination office has functioned in Tashkent, Uzbekistan since 2023. In April this year, Russia’s Ministry of Transport announced the launch of feasibility studies with Afghanistan. In May, Uzbekistan dispatched engineers and its transport minister to Afghanistan for high-level talks with Taliban officials. Tashkent has since announced an ambitious timeline to complete the railway by the end of 2027.

The CPEC: from bilateral corridor to regional architecture

Officially agreed to by China and Pakistan in 2015, the CPEC is a flagship project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Spanning over 3,000 kilometres, it creates a vital trade route from China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Uyghur Region to Pakistan’s Arabian Sea ports, including Gwadar, Port Qasim and Karachi.

So far, China and Pakistan have completed 38 projects worth US$25.2 billion, with an additional 26 projects worth US$26.8 billion planned.

Aiming to enhance trade, investment, economic cooperation and regional connectivity, the US$65 billion project includes highways, railways, pipelines, energy infrastructure and industrial zones. So far, China and Pakistan have completed 38 projects worth US$25.2 billion, with an additional 26 projects worth US$26.8 billion planned.

Strategic pivot: linking the two projects

The linking of the TAR into the CPEC marks a major evolution in China’s infrastructure diplomacy. What began as a bilateral corridor is now poised to form the backbone of a broader transregional network linking China with Central and South Asia and the Arabian Sea, positioning Beijing as both architect and broker of a new Eurasian connectivity order through the BRI. Central to this vision is China’s strategy of building an overland continental trade spine that bypasses maritime chokepoints and sanctions-prone routes through Iran and Russia.

Beijing’s rationale for merging TAR with CPEC is threefold: to streamline Central Asia’s access to global markets via China, to lay the groundwork for cross-border energy and digital infrastructure, and to expand its economic and geopolitical influence through long-term connectivity.

While the exact intersection point between TAR and CPEC remains undecided, one likely candidate is Peshawar, a logistics hub already integrated into the CPEC network and linked to Pakistani ports such as Gwadar and Karachi. This connection would offer landlocked Central Asian countries direct access to the sea, while South Asia would gain overland routes to Central Asia and beyond. Other extensions of TAR may also link with the planned China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, forming an even greater regional transport grid.

Beijing’s rationale for merging TAR with CPEC is threefold: to streamline Central Asia’s access to global markets via China, to lay the groundwork for cross-border energy and digital infrastructure, and to expand its economic and geopolitical influence through long-term connectivity. This approach reflects China’s broader model of influence — relying on infrastructure investment, contracts and development partnerships rather than overt military deployments.

Domestically, the initiative is in line with China’s “Go West” policy aimed at stabilising its underdeveloped western regions. Xinjiang, once viewed largely through a security lens, is now being repositioned as a trade gateway. Kashgar, in particular, is emerging as a logistics hub for export-oriented growth and cross-border integration with Central and South Asia.

However, security concerns remain central to Beijing’s calculus. The East Turkestan Islamic Movement — a militant Uyghurs separatist group active in the Afghanistan-Pakistan borderlands — threatens Xinjiang’s stability. Its calls for an independent “East Turkestan” challenge China’s territorial integrity and national unity. At the same time, its alleged involvement in violent attacks within China fuels fears that cross-border militancy could destabilise the region and derail broader integration efforts.

Energy security is a core motivation behind China’s infrastructure push and willingness to link the CPEC to the TAR. A broader trade route offers alternatives to vulnerable maritime chokepoints such as the Strait of Malacca; a critical vulnerability known as the “Malacca dilemma”.

Approximately two-thirds of China’s maritime trade and 80% of its crude oil imports pass through this narrow strait, making it a strategic bottleneck. By developing overland routes, Beijing can hedge against potential disruptions in sea lanes, thereby enhancing the resilience of its trade and energy supplies while strengthening its strategic presence across Central and South Asia.

The rail corridor will traverse parts of Central and South Asia prone to instability, conflict and terrorism, making it vulnerable to disruption and sabotage...

Challenges: security, terrain and legitimacy

Key challenges remain. Regional rivalries — particularly between Pakistan and Afghanistan — are compounded by fragile state institutions, contested authority, and entrenched militancy.

Security remains the most pressing concern. The rail corridor will traverse parts of Central and South Asia prone to instability, conflict and terrorism, making it vulnerable to disruption and sabotage, from both domestic insurgents and foreign proxies.

Afghanistan’s internal instability, compounded by active terrorist groups and persistent tribal dynamics, further challenges Taliban control. At the same time, Pakistan and China remained concerned about cross-border attacks from terrorist groups. Elevated security risks and soaring insurance costs may undermine the route’s reliability and limit broader commercial use.

However, recent diplomatic engagements suggest a growing political commitment to resolving these challenges. In this year’s May trilateral meeting, the three parties agreed in principle to restore full diplomatic ties and boost cooperation on trade, reconstruction, and regional security, including counterterrorism efforts. Afghanistan and China also jointly committed to preventing terrorist groups from operating within their borders. Nonetheless, such assurances may be hard to enforce.

Technical and engineering challenges add complexity. The railway must traverse some of the world’s most rugged and seismic terrain, necessitating extensive, durable infrastructure in remote and undeveloped areas. Additional bottlenecks include uneven infrastructure, inconsistent customs protocols and poor cross-border regulatory coordination. Track gauge mismatches — Uzbekistan uses 1,520mm, Pakistan uses 1,676mm and China uses 1,425mm — also require time-consuming and expensive cargo transfers.

The linking of TAR and CPEC could fundamentally reshape energy security, trade routes and diplomatic flows across Eurasia by creating a resilient, China-led overland connectivity network. However, enormous political, security, and technical hurdles must be overcome before this transformative vision can be fully realised.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)