Chinese investment in Southeast Asia: Threat to Japan, South Korea and Taiwan?

Academics Guanie Lim and Chengwei Xu compare Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Southeast Asia with that from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. They find that China’s FDI, concentrated in tertiary industries along with construction and real estate, may complement rather than challenge the economic positions of its Northeast Asian neighbours.

In recent years, the rise of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Southeast Asia has sparked considerable debate often framed within the broader context of geopolitical competition.

Take the recently completed Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail (HSR) project, for instance. It was subject to fierce jostling between major Japanese and Chinese firms, with strong political and financial support from both Tokyo and Beijing. When it was announced in late 2015 that the Chinese consortium eventually prevailed, a Forbes report provocatively asked: “How did we lose to China in Indonesia!?” before going on to discuss the worry and disbelief of Japanese bureaucracy and business groups.

Is such a concern justified? After all, almost ten years have passed since the project’s announcement and its completion. More importantly, how much do we know of the FDI dynamics interconnecting China and the rest of Southeast Asia? A recent report co-written by the authors shed some light on the performance of Chinese, Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese FDI over two decades. Several insights are revealing.

... [China’s] FDI is sizeable only in the less developed economies of Southeast Asia: Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

China’s presence exaggerated

Firstly, contrary to common perception, Chinese FDI in Southeast Asia is relatively modest compared to investment from the other three Northeast Asian economies (see Table 1). In particular, Japanese firms have maintained their prominence in the region despite Japan’s subdued post-1990s economic output growth rates.

This is especially evident in Thailand, widely referred to as the “Detroit of Southeast Asia”, where Japanese automobile groups continue to dominate market share and oversee their broader Southeast Asian operations. Other noteworthy mentions include high-end retail, whereby outlets such as Takashimaya and Kinokuniya continue to command a wide following.

While China has undoubtedly increased its economic presence in the region, particularly since the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, its FDI is sizeable only in the less developed economies of Southeast Asia: Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

These nations, which have relatively underdeveloped economies and are essentially latecomers to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) project, present opportunities that Chinese firms have been quick to exploit. In these markets, where less-than-mature institutional framework and business climate may deter more established investors, Chinese firms have found niches, particularly in labour-intensive industries like real estate and petty trading.

China’s “suitcase transnationals” — spotting gaps yet to be exploited by more established firms — simply bring cash and expertise across the border to establish new ventures and partnerships. Owing to their rather low-end technical, organisational, and learning capabilities, business groups in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar have found it more practical to collaborate with their Chinese counterparts than the more sophisticated business groups (from wealthier economies).

In contrast, more developed Southeast Asian economies such as Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand continue to attract substantial FDI inflow from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. These countries have traditionally welcomed global capital, particularly in industries like automobile production, where Japanese firms have long established a dominant market presence. Despite the growing presence of Chinese firms in Southeast Asia, the entrenched positions of Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese companies in these mature markets remain largely unchallenged.

The focus of Chinese FDI on tertiary industries, in addition to construction and real estate, suggests that China’s economic rise in Southeast Asia may complement rather than threaten the position of its Northeast Asian neighbours.

China’s FDI focus: Tertiary industries, construction and real estate

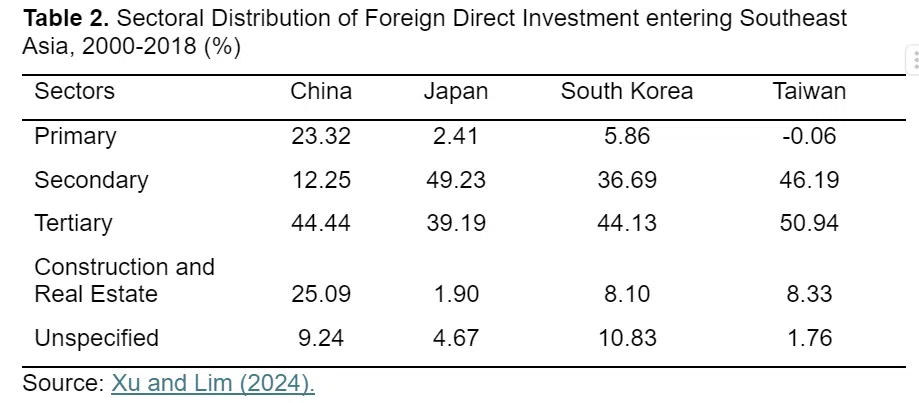

Secondly, Chinese investment is concentrated in the tertiary sector (e.g. trading and finance), in addition to construction and real estate (see Table 2).

In contrast, a larger proportion of FDI from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan has entered the secondary sector (i.e. manufacturing) (49.23%. 36.69% and 46.19% respectively). Only 1.9% of Japanese FDI was channelled toward construction and real estate. In a similar vein, South Korea and Taiwan invested only 8.1% and 8.33% of their total FDI in construction and real estate activities.

This sectoral differentiation significantly reduces the likelihood of direct competition between Chinese FDI and that from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. The focus of Chinese FDI on tertiary industries, in addition to construction and real estate, suggests that China’s economic rise in Southeast Asia may complement rather than threaten the position of its Northeast Asian neighbours.

To understand why Chinese FDI, at least relative to that of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, is so weakly represented by manufacturing interest, it is important to consider China’s domestic economic structure.

Despite the market-oriented reforms since 1978, China’s economy remains dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), particularly in non-tradable industries like utilities, infrastructure, and finance. Secondary sector (i.e. manufacturing) performance remains mediocre, notwithstanding government efforts to groom its cohort of “national champions”.

China’s “dual track” economy is also markedly different from the other more mature economies of Northeast Asia (i.e. post-WWII Japan, South Korea and Taiwan). Unlike China, which relies on its cohort of SOEs (especially in non-tradable industries), the other three economies have generally encouraged the growth of private firms. Several of them have since carved out niches in globally competitive manufacturing industries, including but not limited to Japan’s Toyota (automobile), Korea’s Samsung (consumer electronics) and Taiwan’s Formosa Plastics (petrochemicals).

Structural issues hindering outward expansion

China’s structural weaknesses in manufacturing became increasingly evident in the years following the 2008 global financial crisis. To stave off a rapidly shrinking export market in the global north, the Chinese government implemented aggressive stimulus measures to boost domestic demand. Much of this spending was funnelled into construction and real estate, industries that eventually hit diminishing returns.

Although a meltdown was initially averted, by the early to mid-2010s, issues such as overcapacity and soaring government debt began to surface, hindering economic expansion. As domestic opportunities dwindled, Chinese firms were then encouraged to “go out” and seek opportunities abroad, particularly in Southeast Asia, where these industries still had room for growth. Indeed, these are some of the push factors behind Chinese President Xi Jinping’s 2013 announcement of the ambitious BRI.

However, this outward expansion has not significantly upended the established position of Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese firms, which integrated into the global and regional economies long before China began its reforms. Amongst other things, their early start allowed them to develop world-class firms that went on to dominate key industries.

Put another way, Chinese businesses must overcome the “incumbency effect” of their peers from the three other Northeast Asian economies, in addition to those of Western economies, in expanding their market presence in Southeast Asia (and beyond).

... Chinese resolve to complete projects in a short timespan can be combined with Japanese-style monozukuri (manufacturing spirit), in addition to ASEAN firms’ intimate knowledge of the local and regional market.

Growing East Asia together

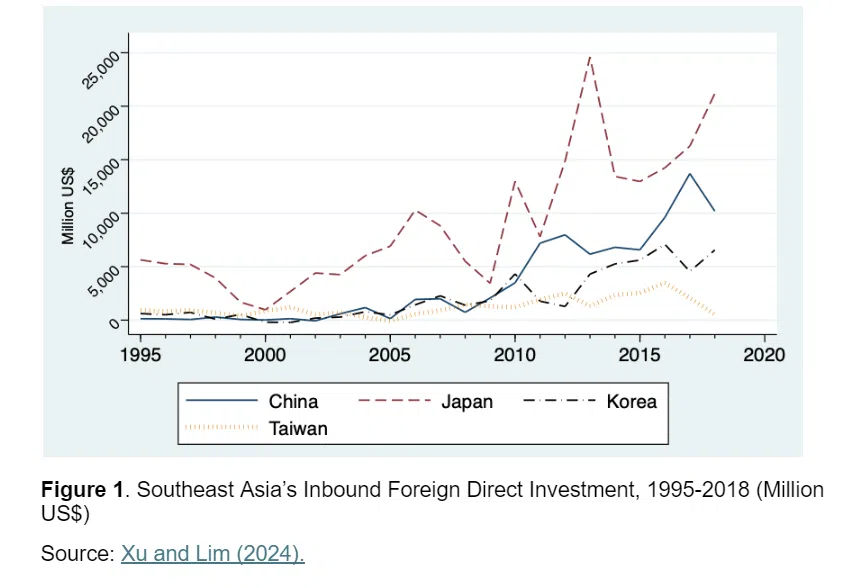

In conclusion, Chinese FDI in Southeast Asia presents a complex picture that defies simplistic narratives of geopolitical rivalry. While China’s economic presence in the region is surely growing, its FDI, at least as of now, is not directly competing with the investments of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. As shown in Figure 1, all four FDI sources have increased their presence, with no clear sign of a secular decline.

The distinct characteristics of Chinese FDI, particularly its focus on non-tradable industries (e.g. tertiary activities and real estate), suggest that it complements rather than threatens the position of its Northeast Asian neighbours. As China continues to expand its economic influence in Southeast Asia, the region is likely to see a more nuanced and multifaceted commercial landscape, where different FDI providers carve out their own niches rather than engaging each other in direct, zero-sum competition.

Future studies should explore the on-the-ground impact on the recipient economies and examine how the latter can strategically leverage different types of FDI and combine the positive elements of the FDI providers’ respective business systems.

For example, Chinese resolve to complete projects in a short timespan can be combined with Japanese-style monozukuri (manufacturing spirit), in addition to ASEAN firms’ intimate knowledge of the local and regional market. These efforts deserve more encouragement and scholarly attention for they contribute to a more meaningful interaction between Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia.