The true price of AI: Water and energy demands behind Asia’s data centre boom

Data centres are fast becoming the backbone of Southeast Asia’s digital ambitions — but their soaring demand for electricity and water threatens to trigger a sustainability crisis. Researcher Genevieve Donnellon-May looks into the issue.

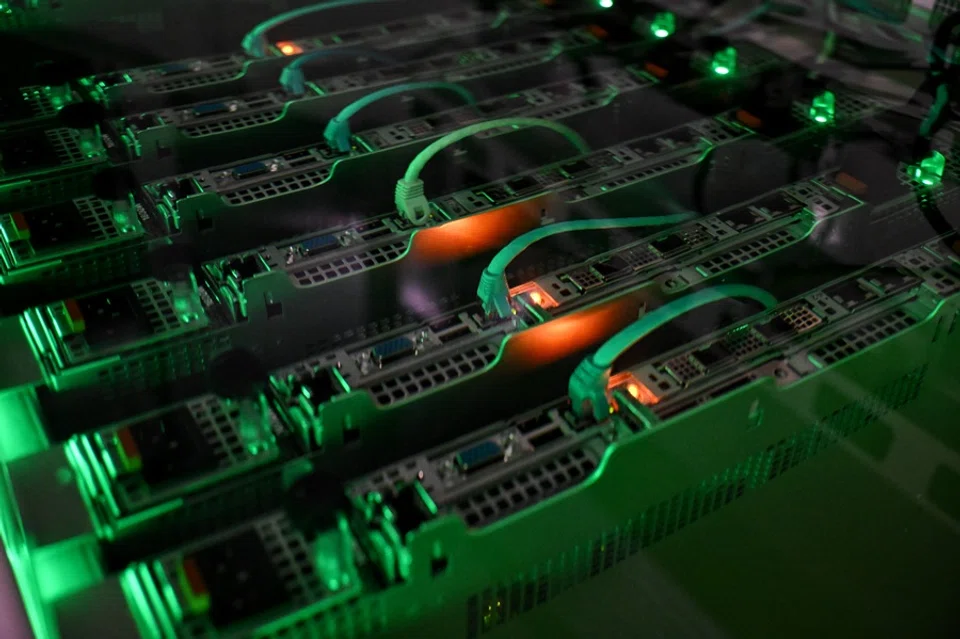

Driven by national digitalisation strategies, rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI), and booming cloud computing, the Southeast Asian region is accelerating its data infrastructure buildout. These facilities — critical for AI training, big data processing and digital services — are now central to Southeast Asia’s economic competitiveness and technological growth.

Yet this progress comes with steep environmental costs. Data centres are highly resource-intensive, consuming vast amounts of electricity to power servers and significant amounts of water to cool systems — especially in tropical climates.

As the region faces mounting water stress from urbanisation, population growth and climate change, its digital expansion increasingly clashes with resource limits. Without coordinated strategies to manage this water-energy nexus, Southeast Asia risks undermining its climate goals and long-term resilience.

Between 2019 and 2023, regional data centre capacity more than doubled — from 0.8 gigawatts (GW) to 1.7 GW.

Asia’s data centre boom

Asia’s digital transformation, driven by AI, cloud services and growing digital economies, has sparked an unprecedented surge in data centre development. Southeast Asia is at the centre of this expansion.

Between 2019 and 2023, regional data centre capacity more than doubled — from 0.8 gigawatts (GW) to 1.7 GW. Its six largest economies — Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam — are collectively developing approximately 2.9 gigawatts (GW) in new capacity. Singapore leads with over 70 operational data centres.

There are no signs of slowing down. The region’s data centre capacity is projected to triple by 2030, reaching between 5.2 GW and 6.5 GW, largely driven by exponential growth in AI computing demand. Data centres are rapidly expanding to support the region’s growing digital economy, cloud computing and AI ecosystems, positioning it as the next major data centre hotspot.

... each 100-word AI prompt alone uses roughly 519 millilitres, or one bottle of water.

Water-energy nexus

Despite mounting environmental concerns, data centre siting in Southeast Asia continues to prioritise land availability, tax incentives and low-cost electricity — often at the expense of long-term water and energy sustainability. This disconnect is intensifying the region’s water-energy nexus crisis.

An estimated 74% of Southeast Asia’s nearly 700 million people already face high water stress, while 347 million in the region endure severe shortages — among the worst globally. Rapid urbanisation, rising temperatures and competing agricultural and industrial demands are further straining fragile water systems.

Data centres exacerbate these pressures. A single AI-oriented facility can consume as much electricity as 100,000 households in the US, with cooling alone accounting for up to nearly 40% of total energy demand. Around 70% of Southeast Asia’s electricity is still generated from fossil fuels, which raises concerns about emissions and grid stability. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects the region’s data centre electricity demand will nearly double by 2030, with national consumption from data centres reaching as high as 30% in some ASEAN countries.

Water demand is rising in parallel. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that a 1-megawatt data centre uses 25.5 million litres of water annually — comparable to the daily needs of 300,000 people. According to scientists at the University of California, Riverside, each 100-word AI prompt alone uses roughly 519 millilitres, or one bottle of water. Adding to concerns, most data centres rely on evaporative cooling, which can lose up to 80% of water through evaporation. Roughly 60% of their total water footprint is indirect — tied to fossil-fuel power generation.

In Johor alone, projected water demand from existing and planned facilities would exceed 673 million litres per day.

The consequences are already evident in Southeast Asia. Notably, Malaysia, aiming to become ASEAN’s Digital Capital and targeting a 35% digital economy contribution to gross domestic product in 2030, is facing resource vulnerabilities. In 2024, Malaysian authorities received 101 new data centre applications, with a combined water demand exceeding 808 million litres per day.

Johor, its fastest-growing data centre hub, exemplifies the resource risks. In Johor alone, projected water demand from existing and planned facilities would exceed 673 million litres per day. As most data centres rely on treated public water — normally reserved for domestic use — for server cooling, Malaysia’s water regulator has warned this is unsustainable given water infrastructure across three states – Johor, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan can supply only 142 million litres.

Climate stress adds urgency. Johor is forecast to face droughts as early as 2025, placing even more strain on water resources.

Without integrated planning and sustainable resource management, Southeast Asia’s digital growth risks undermining the very development goals it aims to achieve.

Addressing concerns

Tackling these challenges demands a multi-faceted approach: enhancing regulatory transparency with stronger environmental reporting and detailed resource metrics — including water footprints — alongside increased investment in water-efficient cooling technologies. Governments and industry must coordinate through clear policies, national frameworks, regional collaboration, innovation in technology and governance, regulatory incentives, and transparent performance benchmarks.

Tencent reports that renewables power 54% of its data centre electricity, with over 70% of its self-built campuses running on green energy.

Crucially, Southeast Asia must accelerate the shift in data centres’ energy mix toward low-carbon, water-efficient sources. With data centres projected to consume as much as 30% of national power demand by 2030, expanding renewables — especially solar, wind, and hydropower — is essential to reduce dependence on carbon- and water-intensive coal power. Research suggests that solar and wind could meet up to 30% of data centres’ electricity demand in Southeast Asia.

Lessons from China

China offers valuable lessons. Home to over 449 data centres and responsible for about 25% of global data centre electricity use, Chinese facilities consumed approximately 140 billion kWh in 2024 — a 31% year-on-year increase — far outpacing the country’s overall electricity growth of 6.8% last year.

In response, Chinese authorities are investing heavily in nuclear and renewable energy. A low-carbon plan issued in July 2024 aims to increase renewable energy use in data centres by 10% annually through 2025, requiring an estimated 40 to 63 billion kWh from wind and solar sources.

The private sector is also driving change. In 2024, Chinese tech giant Tencent’s renewable-powered microgrid project in Hebei, a 10.99 MW facility, China’s first to integrate wind, solar and battery storage onsite, generates 14 million kWh annually for an adjacent data centre. A second microgrid in Tianjin, with 10.54 MW solar capacity, produces 12 million kWh annually. Tencent reports that renewables power 54% of its data centre electricity, with over 70% of its self-built campuses running on green energy.

Without urgent reforms — clean energy shifts, water-efficient technologies and stronger regulation — Southeast Asia’s digital ambitions risk becoming environmental liabilities.

Regional cooperation even more crucial than before

Outside of Asia, Microsoft will pilot zero-water evaporated designs at new US facilities from 2026, while Amazon plans to expand its use of treated wastewater for data centre cooling from 20 to 120 data centres by 2030. If successful, these initiatives serve as models for Southeast Asian data centre operators.

Regional cooperation is also critical. Platforms such as the China-ASEAN Belt and Road Green Development Partnership, ASEAN Smart Cities Network and ASEAN-China Ministerial Meeting on Science, Technology and Innovation provide avenues to harmonise environmental standards and cross-border technology exchange and sharing of best practices. New initiatives like the planned China–ASEAN AI Cooperation Centre demonstrate interest in collaborative data centre development.

Without urgent reforms — clean energy shifts, water-efficient technologies and stronger regulation — Southeast Asia’s digital ambitions risk becoming environmental liabilities. Embedding sustainability into infrastructure planning is no longer optional. The region’s ability to lead the next tech wave hinges on getting this balance right.